Israel’s stunning attacks on Hezbollah via exploding pagers and walkie-talkies demonstrate both the creativity and cunning of its intelligence and defense forces, and their capacity to strike deep into the heart of its adversaries’ domains. The casualties among Hezbollah’s top leadership (and allies, like Iran’s Ambassador to Lebanon) plus the significant near-term degradation of Hezbollah’s internal command-and-control, make it conspicuously vulnerable.

For Americans, the death of senior Hezbollah leader Ibrahim Aqeel is especially significant. He was responsible for the 1983 bombings of the US embassy in West Beirut, and of barracks for US Marines and French soldiers participating in a multilateral peacekeeping force, at the government of Lebanon’s invitation. At least partial justice has been done.

Together with the recent elimination of Hamas leader Ismael Haniyah in a supposedly secure compound in Tehran, Israel has almost certainly unnerved Iran, its principal enemy, as well as the terrorist proxies directly targeted. While the future is uncertain, now is a perfect opportunity for Israel to take far more significant reprisals against Iran and all its terrorist proxies for the “Ring of Fire” strategy. Iran’s nuclear-weapons program may now finally be at risk.

Where does the Middle East battlefield now stand?

After “Operation Grim Beeper,” as many now call it, Jerusalem launched major strikes against Hezbollah targets in Lebanon. Whether these strikes have concluded, or whether they are the opening phases of a much larger anti-terrorist efforts, is not clear. These and other recent kinetic strikes have caused further damage to Hezbollah’s leadership and its offensive capacity.

Nonetheless, Hezbollah’s extraordinary arsenal of missiles, largely supplied or financed by Iran, plus their ground forces and tunnels networks in the Bekka Valley and elsewhere in Lebanon, make it a continuing threat, more dangerous near-term to Israel than even Iran. The CIA publicly estimates the terrorists could have “as many as 150,000 missiles and rockets of various types.” Many believe it is a matter of simple self-preservation that Israel must neutralize Hezbollah before any significant military steps are taken against Iran itself.

Since October 8, the day after Hamas’s barbaric attack on Israel, Hezbollah’s constant missile and artillery barrages into northern Israel have forced approximately 60,000 citizens to evacuate their residences, farms and businesses. Because of the extensive economic dislocation, and the continuing danger of further destruction of the abandoned properties, on September 16, Israel declared that returning those forced to flee from the north to be a national war goal. That could well signal further strikes. Israel has maintained near-perfect operational security for nearly a year; no one on the outside can predict with certainty what is coming.

As for Hamas, a less-reported but equally significant development is that the Biden administration seems to have largely given up hope of negotiating a cease-fire in the Gaza conflict, at least before November’s presidential election. In fact, Israel and Hamas had opposing goals that could not be compromised. Israel was prepared to accept a brief cease fire and releasing some Palestinian prisoners, in exchange for its hostages, whereas Hamas wanted a definitive end to hostilities, with all Israeli forces withdrawing from Gaza. Almost certainly, there was never to be a meeting of minds.

Accordingly, Israel’s pursuit of Hamas’s remaining top leadership and the ongoing efforts to degrade and destroy its combat capabilities will continue. Moreover, operations to destroy Hamas’s extraordinarily extensive fortifications under Gaza will also continue, aimed at totally destroying every cubic inch of the tunnel system. Thus, at least for now, Iran’s initial sally in the Ring of Fire strategy is on the way to ignominious defeat. Tehran’s dominance in Gaza has brought only ruin.

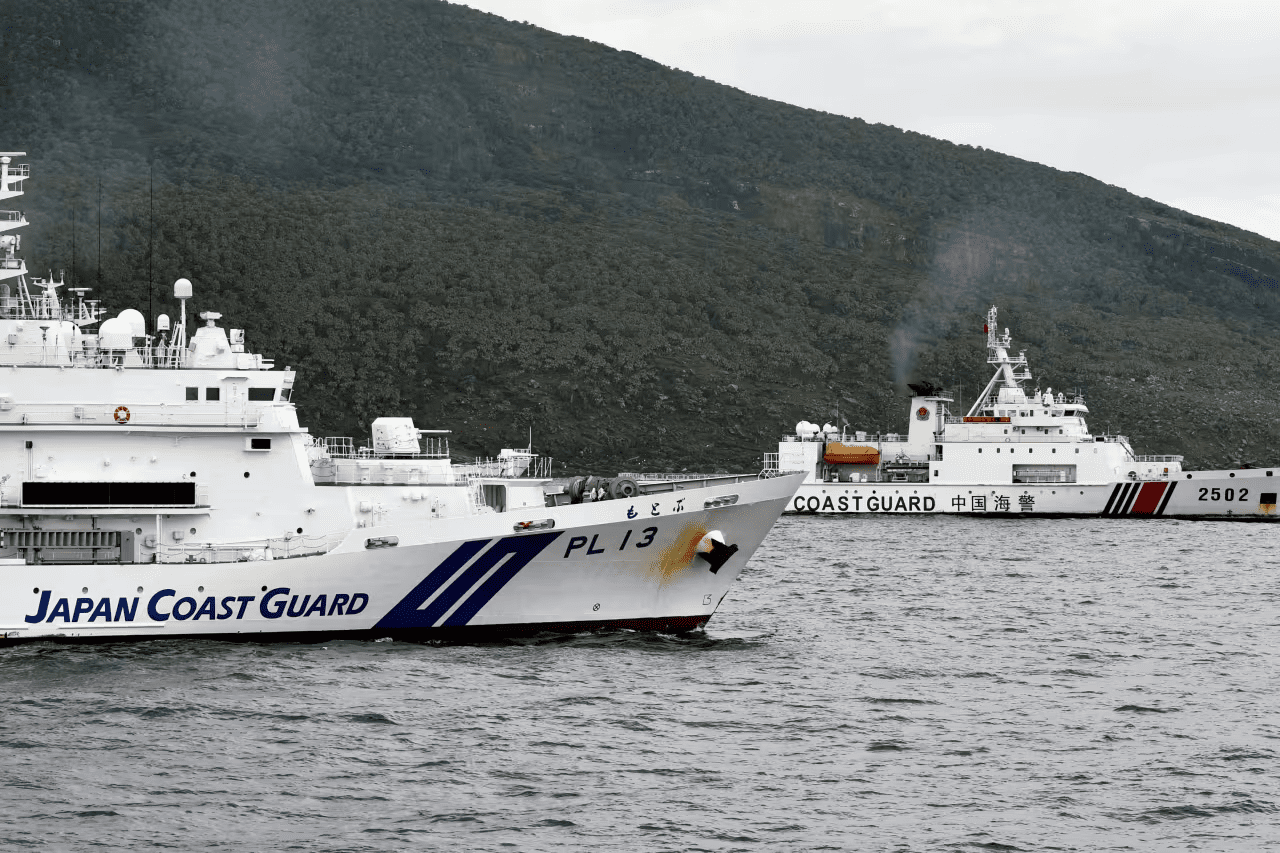

By contrast, Yemen’s Houthi terrorists, with Iran’s full material support and political direction, continue to close the Suez Canal-Red Sea passage to most traffic, while also targeting US drones in international airspace. This blockage us causing significant economic hardships. In the region, Egypt is suffering major declines in government revenue from lost Suez Canal transit fees, which can only increase economic hardships for its civilian population. Worldwide, the higher costs of goods that must now be transported around the Horn of Africa are burdening countless countries, all with impunity for the Houthis and Iran.

Allowing Tehran and its terrorist proxies to keep these vital maritime passages closed is flatly unacceptable. Even before the United States was independent, freedom of the seas was a key principle of the colonies’ security. As with many other aspects of Iran’s Ring of Fire strategy, the Biden administration has been wringing its hands, not taking or supporting decisive action to clear these sea lines of communication. Whether the next US President continues the current ineffective approach will obviously not be known until after January 20, 2025.

Similarly, the United States has failed to exact significant retribution against Iran and the Shia militias in Iraq and Syria, also largely armed and equipped by Iran, that have conducted over 170 attacks on American civilian and military personnel since October 7. The Biden administration has effectively left these diplomats, soldiers and contractors at continuing risk, especially as tensions and increased military activity in the Ring of Fire area of operations escalate. An Iranian or Shia militia attack that inflicted serious American casualties, which is unfortunately entirely possible due to the Biden administration’s passivity, could prompt major US retaliation, perhaps directly against Iran.

Tehran’s mullahs remain the central threat to peace and security in the Middle East. As its terrorist surrogates are steadily degraded, and the Ring of Fire Strategy increasingly unravels, the prospects for direct attacks on Iran’s air defenses, its oil-and-gas production facilities, its military installations, and even its nuclear-weapons and ballistic-missile programs steadily increase, Moreover, as Iran’s deeply discontented civilian population sees increasingly that the ayatollahs are more interested in religious extremism than the welfare of their fellow citizens, internal dissent against the regime will increase. The real question, therefore, is whether Iran’s Islamic Revolution will outlast its current Supreme Leader.

This article was first published in Independent Arabia on September 24, 2024. Click here to read the original article.