Misguided opposition in the Senate bodes ill for U.S. Mideast policy in the Biden administration.

This article appeared in The Wall Street Journal on December 6, 2020. Click here to view the original article.

By John Bolton

December 6, 2020

Senate opposition to the proposed U.S. arms sales to the United Arab Emirates reflects a dangerous reversion to the Obama-era understanding of the Middle East. While opponents of the deal claim that the Emirates have misused other U.S. weapons in Yemen, the real issue is much broader.

A Senate vote on legislation to halt the $23 billion arms deal is expected in days. While opposition will likely fail—even if the bill passes, supermajorities would be needed to override the expected presidential veto—the thinking behind it foreshadows an ill-advised Biden administration policy toward Iran.

The Iranian threat to regional peace and security has altered the strategic reality of the Middle East since the misbegotten 2015 nuclear deal. Arab states increasingly fear Tehran’s nuclear weapons and ballistic missiles, but also its support for terrorism in Yemen, Lebanon, Syria and Iraq, as well as its conventional military activities. The decision by Bahrain and the U.A.E. to establish full diplomatic relations with Israel shows how Iran’s increased—and largely unchallenged—belligerence has realigned the Middle East’s correlation of forces.

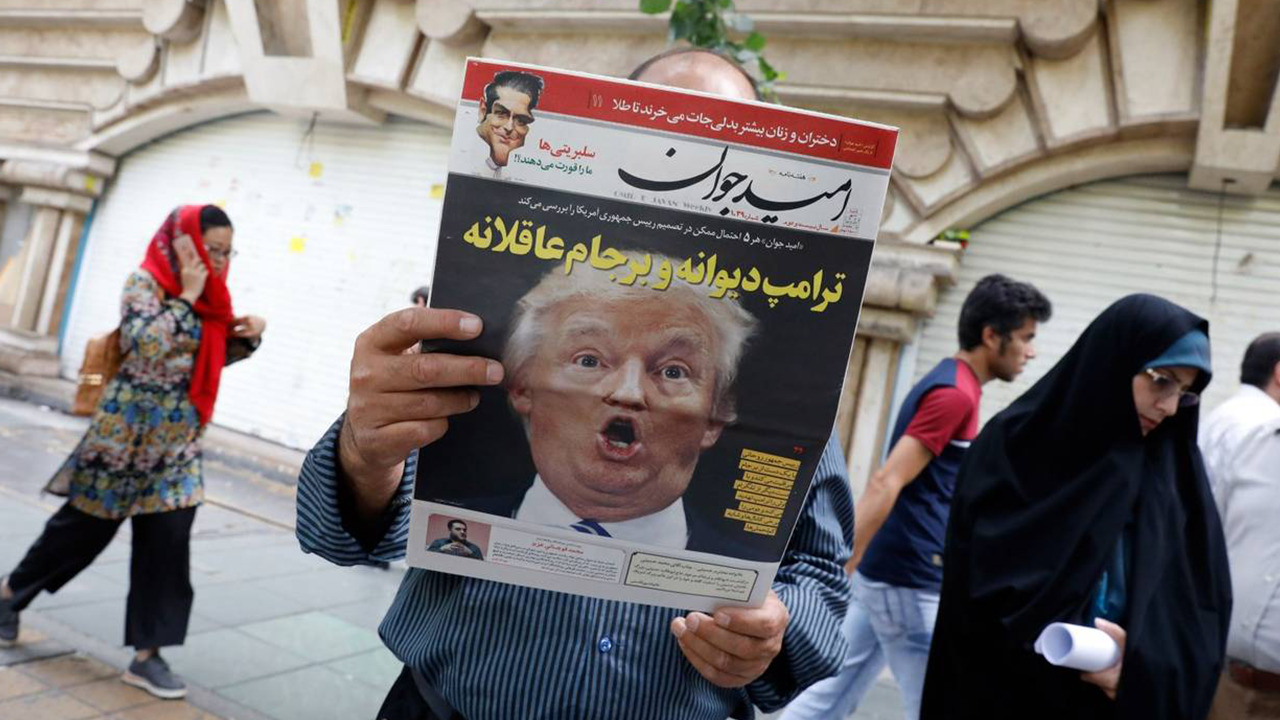

Many of these shifts stem from the nuclear deal, which released between $120 billion and $150 billion in frozen assets and freed Iran from arduous economic sanctions, providing Tehran the resources to expand its military and clandestine capabilities. Iran’s Quds Force used its share of the windfall to beef up support for Iraqi Shiite militias, Syria’s Assad, and Hezbollah in Lebanon and Syria. In response, the Emirates and other U.S. friends rightly want more-advanced arms.

Less reported, but of vital importance to the Gulf Cooperation Council’s six Arab member states, was Iran’s dramatic expansion of support for Yemen’s Houthi rebels. Previous Iranian aid to the Houthis had been intended to stalemate Saudi and Emirati efforts to install a stable, pro-GCC government in San’a, but in 2017 Tehran ramped up shipments of sophisticated weaponry that could strike far beyond Yemen’s borders. This threatened Saudi Arabia’s oil infrastructure; important civilian airports in Riyadh, Dubai and Abu Dhabi; and commercial shipping in the Red Sea and the Bab el-Mandeb Strait, critical sea lanes to the Suez Canal.

The Gulf Arab states are entirely justified in resisting Tehran’s intrusion into their backyard. Yemen’s conflict has had more than its share of brutality, much of it caused by the Houthis’ inhumanity and ruthless exploitation of food-aid programs. Iran’s intervention and cynical manipulation of the disarray has compounded the humanitarian problem.

Blocking arms sales to the U.A.E. or Saudi Arabia wouldn’t ameliorate conditions in Yemen. The Emiratis have scaled back their involvement, and the Saudi-led coalition has taken much-needed steps to avoid civilian casualties. U.S. weapons are needed more urgently to defend against Iran’s threat in the Gulf. U.S. vacillation could thwart the emerging Israeli-Arab template for regional peace and stability. The Arabs are deeply concerned by President Trump’s policy gyrations, including troop withdrawals from Iraq and Afghanistan. They fear that under Joe Biden the U.S. presence will recede further, leaving them increasingly vulnerable to Iran’s aspirations for hegemony.

Unlike in years past, Israel doesn’t object to the proposed arms deal. While it is too early to call Israel’s ties with the Arabs “alliances,” such relations could arise. In any case, they are all U.S. allies. Strengthening these links benefits America.

Other than virtue signaling, what conceivable reason is there to oppose arming a vulnerable ally, the U.A.E.? The most troubling possibility is that Mr. Biden and Senate Democrats cling to the romantic notion that Tehran’s ayatollahs long to join “the international community.” If only America and its regional allies dropped their hostility and Washington rejoined the 2015 deal, the argument goes, Iran’s nuclear-weapons and ballistic-missile programs would cease to be problems. Other issues could be negotiated and the Middle East would be at peace. This was nonsense in 2015 and still is.

The Biden team stresses constantly the need to strengthen relations with allies—conventional wisdom for all but Mr. Trump. But not every ally thinks alike. America’s Middle Eastern friends, who live well within range of Tehran’s missiles, drones, terrorist proxies and conventional forces, don’t buy the “peace in our time” theory. U.S. allies in Europe want to revitalize the nuclear deal, but does it tell us anything that Russia and China agree?

This is an early test: Does Mr. Biden know that Iran is the biggest threat to regional security? Will he realize how dramatically the ground in the Middle East has shifted?