By Dr. David Wurmser

May 12, 2021

Sadly, there seems to be an escalatory effort underway within Israel, in the administered territories in Judea and Samaria, along Israel’s northern and Gaza borders, and even globally which could lead to great tension, even war, in the coming months. This is not a mutually reinforcing cycle of violence between two sides, but a concerted offensive serving strategic aims of a number of Israel’s enemies.

There is no one cause for this escalation. Rather it results from a collection of forces and strategic interests converging. Like the epic art of Middle Eastern story-telling, the singular “umbrella” theme of escalation is actually the product of many separate sub-tales woven into other tales, which align into a shell or framework story. In this case, that unifying shell tying these separate tales together represents a very real moment of danger.

The signs of escalation were building for weeks. In early April, there was a sudden escalation of attacks on Jews, many of which were serious and violent enough to result in hospitalization. As the Palestinian Media Watch, and FLAME – an organization dedicated to accuracy in media – note, the Palestinian official media organs started to broadcast highly inflammatory and bloody rhetoric starting on April 2. Two particularly disturbing attacks, one a beating by three Arab youths of a Rabbi in Jaffa, the southern part of Tel Aviv, and another wherein an Arab spilled boiling liquid on a Jew entering the Old City of Jerusalem, were followed by violent Arab demonstrations when police attempted to arrest the perpetrators.

Palestinians conducting these attacks in early April filmed their exploits and posted them to TikTok to compete over the amount of “likes” and “approvals” they can draw. So prevalent was this wave of Palestinian attacks on unsuspecting Jews who were minding their business in normal daily circumstances that the whole escalation was dubbed the “TikTok Intifadah.”

After two weeks of these violent attacks, a small group of extremist Jews marched in the streets of Jerusalem calling for the harming of Arabs, and a small demonstration was organized in Jaffa on April 20, near the area of the Rabbi’s attack. There were no acts of Jewish demonstrations prior to that. There were also one or two localized acts of anonymous Jewish graffiti-spraying with hateful slogans, and even the destruction of a few trees. But these incidents were isolated, limited and Israeli authorities investigated and will prosecute them. Moreover, subsequent investigations, even by leftist human rights organizations like BeTzelem, have even much to their chagrin later been forced to admit they had been misled and thus must retract some of their accusations of Jewish violence, particularly arson, which turned out, in fact, to be acts of Palestinian arson. Actual Jewish demonstrations and disturbances were quickly suppressed by Israeli police and have largely disappeared.

In contrast, Arab demonstrations have accelerated, expanded, broadened geographically and become increasingly violent. And the leadership of the Palestinian Authority (PA) continues to use its media outlets not to calm the flames, but to pour high-octane fuel on them. Incitement includes songs and chanting of slogans calling for martyrdom and blood in their children’s programs across all age groups, even toddlers.

Another series of attacks focused on the Damascus Gate into the Old City. This campaign of violence, especially a series of beatings of Jews and riots in Jerusalem, Jaffa and at the Damascus Gate on April 12, led Israel to set up barriers on April 13, to control flow, keep potentially violent Jewish and Arab extremists separated and maintain pedestrian traffic control to segment and respond quickly to rioting attempts by either. When a large number of Arab agitators quickly surged toward the area that evening, the barriers proved inadequate, and several days of escalating nightly Arab riots against Israeli police ensued, which eventually provoked a smaller Jewish demonstration and unrest on April 20, after a week of Arab riots and numerous beatings of Jews.

It was not long before the border with Gaza heated up as well, and rockets began being launched from Gaza into Israel, with one night in late April registering nearly three dozen rocket attacks onto Israeli towns and cities near Gaza. The northern border heated up as well, with an increased pace of activity by Iran’s IRGC to establish its ability to attack Israel, followed by a series of Israeli strikes in Syria to diminish that capability. After one Israeli strike, a stray Syrian SA-5 missile flew nearly 200 km across Israel and landed near Israel’s nuclear reactor in Dimona.

In the first week of May, the escalation continued. The Palestinian Authority then formally cancelled its planned elections and blamed Israel for the cancellation, after which the long silent head of the Hamas military structure, Muhammad Deif, suddenly resurfaced to call for violent attacks on Israelis, to also include “hit and run” attempts to run over Israelis. On May 2, live fire weaponry was re-introduced when a Palestinian terrorist, Muntazir Shalabi and a driver, machine-gunned three Israelis waiting at a bus stop at Kfar Tapuah Junction in Samaria in the territories. One Israeli teenager, Yehuda Guetta, died and another is in serious condition. A third escaped with moderate injuries. Yehuda Guetta was the first Israeli to die as a result of live fire in a terror attack in months, even years.

Moreover, violent demonstrations also erupted against a cluster of Jewish houses in the southeast Jerusalem neighborhood of Shaykh Jarrah near the US embassy. The Jewish presence in this cluster of houses was not a new Israeli move; the claim was based on an old Jewish-held land-deed from early in the 20th century. But this Jewish presence in the heart of an otherwise Arab neighborhood in Jerusalem was quickly attacked as a target of opportunity in early May – a propaganda point which was quickly and unquestioningly adopted by some in the US on the left, as several major Democratic leaders, including Elizabeth Warren called the Israeli presence an “abhorrent” and “illegal” settlement.

These demonstrations in Shaykh Jarrah became more violent every day, with Arab arson attacks and the hurling of thousand of projectiles (chairs, bricks, rocks, etc.), which was met by the reinforced presence of armed Jews and police in the house cluster. Hamas warned that if the Israelis do not yield and leave the housing cluster, the violence will escalate.

Hamas delivered on its threats very quickly on another front. On May 5, Hamas from Gaza resumed their incendiary balloon attacks, which included this time not only incendiary devices attached to set fires in Israeli fields, but small bombs as well which could have caused considerable personal injury or death had any one of them had landed close to Israelis.

On Friday May 7, Israeli forces stopped a heavily armed squad originating in Tulkarem which was attempting to enter central Israel. Israeli forces identified the terrorists although they were driven in a minibus with stolen Israeli tags to facilitate entry into central Israel. When stopped, the three terrorists exited the minibus and initiated firing near the Salem military base checkpoint but failed to injure a single Israeli while two of the three terrorists were killed.

Finally, by nightfall on May 7, riots had erupted on the Temple Mount, with hundreds injured, including many police. Rioters retreated into the mosques on the Temple Mount, and police were forced to take positions up near them. This promises to put Israel in the difficult position of being accused of “aggressions” against the Temple Mount and threatening the “status quo.” Indeed, there is every indication already that this will soon cause a crisis in Israeli-Jordanian relations. In fact, the concept of status quo is odd to begin with since over the last two decades the status quo has been fluid rather than static. But the flow has always been in one direction alone. As any visitor to the Temple Mount over the last four decades can attest, the idea of a rigid “status quo” on the Temple Mount has proven to be an illusory concept masking the constantly expanding challenge to Israeli sovereignty, let alone Jewish and Christian access to the Temple Mount, at the hands of the increasingly restricting Muslim Waqf.

Finally, despite serious concerns over a complete loss of control Israeli police allowed Muslims to ascend the Temple Mount on Saturday night, May 8, to mark Laylat al-Qadr – one of the holiest days in the Muslim calendar, but one which is often marked by violence and emotion. With great effort and caution, the night passed without a serious eruption and loss of control, despite the fact that nearly 100,000 Muslims came to the limited space of the Temple Mount complex.

Indeed, despite all this escalation and violence over six weeks, not one Arab rioter has suffered serious injury, let alone be killed, although there are dead and critically wounded Israelis.

In short, Israel faces a concerted escalatory campaign which promises to deliver a hot summer. But why?

The context of this escalation is a willful policy of seeking to provoke a climate of tension which was first started by Muhammad Abbas (Abu Mazen), the head of the PLO and Palestinian Authority, but expanded to other players who had equal strategic reasons to seek upheaval.

Early this year, against the advice of most of his closest aides, Abu Mazen called for the first Palestinian elections in well over a decade for the end of May. Whatever Abu Mazen’s calculations were, it appears to have been a horrible miscalculation. By the end of March, it was painfully clear to him, his aides, his allies, his enemies, and to most international observers that not only will he not win the upcoming elections, but that he will be trounced with both Hamas’ and Marwan Barghouti’s faction of the PLO defeating him.

To avoid such a devastating humiliation, it was clear by very early April that Abu Mazen would have to cancel those elections, which he in fact eventually did the first week of May. And yet, cancelling the elections was not so simple, since both Abu Mazen’s aides and Hamas leaders made it clear that the latter would take to the streets in a violent upheaval against the PA and Abu Mazen were he to proceed to cancel the elections. Abu Mazen had no way out of this dilemma other than to proceed in cancelling the elections, but at the same time blame Israel and provoke a series of escalations that would externalize the anticipated violence and deflect it onto Israel.

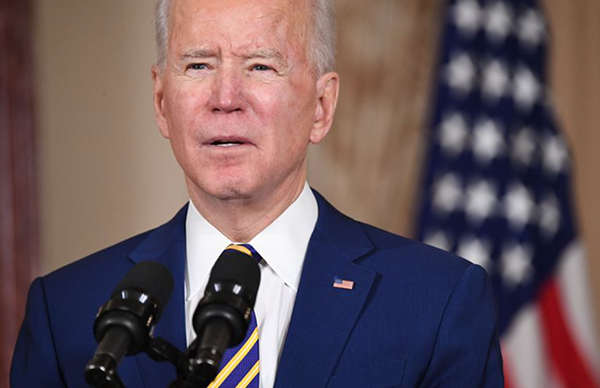

A broader context also has intruded, about which there is building evidence. Several actors, both Palestinian factions as well as external actors such as Iran and Turkey, see a need and opportunity to incite escalation against Israel on many fronts, of which popular unrest was the first phase. In terms of need, the escalatory interests of the Palestinian Authority, Erdogan’s government in Turkey, the revolutionary regime in Iran — emanate from a sense of threat to their regimes from a fear of public rejection and internal unrest. All face grave crises internally that rattle their regimes in dangerous ways. On the other side, in terms of opportunity, the escalatory aspirations of all these actors emanate from the growing confidence that any increase in violence surrounding Israel will cause tension under the new Biden administration between Jerusalem and Washington, thus providing a strategic incentive to engage in just such an escalation. Other than the previous administration, and to some extent the Bush 43 administration, such a reflexive reaction to reign Israel in, and the resulting frustration of Israeli power and initiative, was a safe bet. As such, this sort of escalation, in the form of a test as well, has been a consistent theme greeting every new administration in which there was hope that they may be less pro-Israeli.

Finally, there is an internal Israeli dimension too. There is great shock and discomfort in traditional Israeli-Arab parties and elites in Israel. In the recent elections, an Arab party, the United Arab List (Ra’am) under Mansour Abbas, gained almost as many seats in the Israeli parliament (Knesset) as the traditional leadership represented by the Joint Arab List party led by Ayman Odeh. Mansour Abbas’ party gained this traction because the Israeli Arab population is facing a series of grave crises in such areas as crime, education, economy and so forth. There is popular erosion of support for the traditional leadership since it fails to deliver on such personally important issues. And patience is stretched for continued sacrifice for the elites’ obsessive, theoretical support for unattainable nationalist aspirations.

In a stark departure from the practice of reigning Arab-Israeli elites, Mansour Abbas’ party promised to work within the framework of any Israeli government as a normal parliamentary party to secure the interests of its constituents. Rather than respond competitively, however, the “establishment” Joint Arab List continued peddling an entirely disruptive, anti-Zionist pan-Arab nationalist agenda, which sacrificed its ability to enter the parliamentary power structure to leverage and barter for constituent interests, and instead continued to opt for international applause for its rhetorical, but entirely disenfranchising, nationalist behavior. As such, this internal Israeli Arab traditional leadership anchored to the Joint Arab List also instigated some violence in recent months in order to embarrass and undermine the rising support for the Ra’am (the United Arab List) party. The Joint Arab List under Odeh even provoked direct violent attacks on Mansour Abbas and some in his party in Umm al-Fahm last month. One of the aims of this tension then is to shame Ra’am’s leadership enough to force it into expressing support for the unrest, which would sabotage the party’s ability to deliver on its promise and enter an Israeli government.

As such, the interests of a panoply of actors now dovetail into a dangerously escalatory and mutually-resonating climate enflamed by the United Arab List, the PA, Hamas, Islamic Jihad, Turkey and Iran. Each player has contributed a sub-tale to this story, but the shell, or “umbrella” story is the larger and unifying tale of escalation.

Thus, the unprovoked Arab rioting, the climate of tension created by the impressive performance of the United Arab List in the Israeli elections, followed by the violence instigated at the behest of Abu Mazen and then Hamas and Islamic Jihad, are not the whole story. Given the interests that seem to be in play, it is likely that they are a prelude to attempts to lay the groundwork for a more dangerous escalation in the coming days and weeks, serving not only the interests of diversion noted regarding Abu Mazen, but foreign actors who seek to drive a wedge between Israel and the United States.

A final, disturbing and novel dimension of this current escalatory cycle is that it is attended by a considerable footprint from US territory. First is the advance propaganda campaign, clearly coordinated, to provide a proper background to set a narrative in the United States favorable to this escalation and multiply the tensions it will cause in US-Israeli relations. With blazing speed after the PA and Hamas had signaled there will be an escalatory cycle, pro-Palestinian voices in the United States mobilized to secure this narrative. The Middle East Institute’s Khaled Elgindy, publishing in Foreign Policy, is for example a revealing example of the effort, when he wrote:

“The unrest began on April 13—around the start of Ramadan—when Israeli authorities blocked off the steps to the Old City’s iconic Damascus Gate in Palestinian East Jerusalem. The seemingly arbitrary move sparked several days of clashes between Palestinian protesters and Israeli security forces.”

Of course, there was nothing arbitrary about Israel’s moves at the Damascus gate on April 13, since for weeks before the restriction, accelerating numbers of unprovoked attacks, as incited by Palestinian leaders, occurred on Jews in both Jerusalem and in Jaffa. A focal point of many of these attacks not only in recent weeks, but months and over the last year, which also included several incidents against police, was at the Damascus Gate. So the restrictive barriers set up at the Damascus Gate on April 13, are the inevitable consequence of the escalatory ramp the Palestinian leadership itself had ascended.

So why did the author set the date as April 13, to use his term an arbitrary mile-marker midstream in a series of escalating activities? Because it is the start of Ramadan. The implication is insidious: the Israelis chose to, out of the blue, attack Muslims in Jerusalem on that day of all days since it marked the beginning of the most holy month. In other words, Israel is subtly accused of launching a grave religious attack on Islam itself – a highly incendiary implication.

As such, Khaled Elgindy’s article must be characterized not as an attempt to illuminate, but much more as an attempt to serve as a calculated propaganda offensive coordinated with the determined effort of escalation started by Abu Mazen but now joined by Hamas and Islamic Jihad as well as Iran and Turkey. The use of the word “arbitrary” to characterize Israeli actions — a clever propaganda device used not only to obscure, but entirely erase all context and preceding causes to an action — betray this as an attempt at propaganda rather than effort to bring understanding.

A second, disturbing U.S. aspect of the current escalation is the role – the money to which must be followed –a village in the northern territories in Samaria played from which the terrorist that killed the Israeli citizen, Yehuda Guetta, early this week is from. Not only is the terrorist himself (Muntazir Shalabi) a US citizen, but 80% of the village (Turmus Ayyeh) from which he originated his action is inhabited by U.S. citizens, many of whom are generally absentee, coming only during the summer months. This village has also become a Mecca of sorts for Western pro-Palestinian activists and radicals. An effort to follow the money behind this is warranted.

The Shaykh Jarrah neighborhood issue has tremendous implications and any ruling or Israeli concession could have far-reaching and highly destabilizing repercussions. The issue of the Shaykh Jarrah neighborhood is complex. It is the site of the holy graves of a 12th century Muslim Shaykh who was Salahdin’s doctor, from which the area derives its modern name, and the 5th century BC grave of Simon the Just – the last of the original clerics who returned with the Jewish people from Babylon and started the interpretation structures that make up today’s Jewish liturgy called the Mishna. The sub-neighborhood, Shimon HaTzadik is named after him. There is historical importance, but indeed, there is even more legal and strategic importance to the area.

The neighborhood’s three sections housed about 125 Arab families in 1948, most of whom had moved there in the 1930s and 1940s — some of those families only used the houses as retreats such as the Husseini and Nashashibi families — and about 80 Jewish families who had lived there year-round since the Ottoman era. In early 1948, the area was successfully secured by the Harel brigade of the Haganah as part of the Jewish-Arab-skirmishing in advance of the declaration of the State, but British soldiers, not Arabs, attacked and removed the area from Israeli control, forcing the Jewish families to leave, and turned it over to Arab forces. Shortly afterwards, on April 13, 1948, a British “protected” Jewish resupply convoy to the Israeli enclave on Mount Scopus was attacked by Arab soldiers. The British remained neutral, despite their obligation to protect the convoy, and observed the resulting massacre of 78 Jewish doctors, nurses and civilians. This effectively left Mount Scopus and the Hebrew University cut off from the remainder of Israel. A few years later, when the area was under Jordanian control, UNRWA (United Nations Relief and Works Agency for Palestine Refugees in the Near East) and the Jordanian government transferred several Arab families into the vacant Jewish houses.

When Israel reoccupied the area in 1967, which is in the strategic triangle between the green line, the French Hill, and GIvat Hamiftar connecting Israel to Mount Scopus, the Jewish families who had been expelled two decades earlier asserted their land deeds. A decision by Israel’s Supreme Court in 1972 ruled the Jewish claims were valid, and thus ownership was theirs, but also ruled that for practical reasons, any Arab family that occupies a house will be protected from eviction if they agree to pay rent to the Jewish owners. Recently, Arabs have come forward with counterclaims, all of which are proving to be forgeries – which is not surprising since the land claims from the Ottoman era are in Ottoman archives in Istanbul, and the Turkish government under Erdogan several years ago launched an effort to cull all the land deeds in Israel from the Ottoman era, and are strongly suspected of systematically destroying original Jewish deeds and creating new forgeries.

At any rate, in 1972, a number of families did accept the Israeli Supreme Court formula and paid rent, but a much larger number of families simply ignored the rule of law and refused to pay. The current issue of eviction is about some of those families who have refused to pay rent since 1972 in houses whose Jewish title was incontrovertibly established.

The Shaykh Jarrah issue is strategic for two reasons. First the area connects the Jewish areas of Jerusalem to the Hebrew University, Mount Scopus and several large Jewish neighborhoods to the north. Second, and perhaps much more ominously, if the Jewish claims were annulled, then this would encourage a massive effort to challenge all Jewish claims to any property in Jerusalem, such as the Jewish Quarter of the Old City, and perhaps throughout Israel.

Equally disturbing are the highly incendiary and destabilizing claims of US Democratic politicians, such as Elizabeth Warren, that the Jewish land ownership deeds constitute an “abhorrent” and “illegal” act of occupation and settlement. Such statements either display such insensitivity to, or ignorance of, the history of the neighborhood that it effectively should annul the validity of their participation in discussions, or worse, an anti-Semitic outlook that holds that Jewish titles and land deeds simply do not count and are less valid than anyone else’s anywhere else in the world. One can only hope the motivation is ignorance. Nonetheless, the statements have encouraged the violence and greatly inflamed the situation as it encourages Arab rioters to believe their violence is gaining traction. The statements by the US government, while less flagrantly ignorant or prejudicial, have been weak and disturbingly neutral as well, which also enflames the situation.

The Israeli Supreme Court on May 9, decided to postpone the issue, clearly to buy time to avoid playing into the highly escalatory climate encouraged by Hamas and the Palestinian Authority, but this issue will rear again soon, if not immediately since postponing may not buy calm at any rate and the Arab rioters enjoy international support.

The coming months, thus, will be tense for Israel, and quite possibly very violent. The failure of the United States to preemptively and strongly signal that it will not allow a wedge to be driven between Washington and Jerusalem, and indeed the strong expectation that the opposite will occur, only further encourages the eruption of violence, which aligns with the underlying interests of the various Palestinian factions and surrounding ambitious Turkish and Persian neighbors.