Biden officials’ urgency about emissions makes them likely to sacrifice more-important goals.

This article appeared in The Wall Street Journal on February 3, 2020. Click here to view the original article.

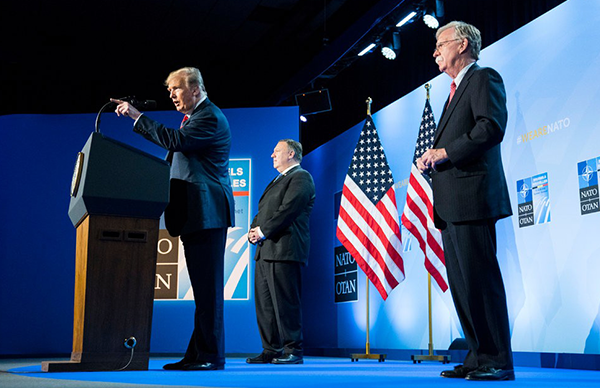

By John Bolton February 3, 2021

President Biden is eager to make climate change a central issue, and he can expect an intense debate. The trade-offs are complicated and the politics are difficult and uncertain. But the biggest challenge may be international, particularly dealing with China, America’s pre-eminent adversary. Does the Biden administration have the slightest idea how to reconcile its global environmental goals with its China strategy?

The early signs aren’t encouraging. Right or wrong, climate change wasn’t on President Trump’s priority list for dealing with China. But it is paramount to Mr. Biden. In Beijing’s eyes, this makes Washington the demandeur—in diplomatic parlance, the one asking for something. It is never a preferred position in negotiations. You want China to take action on climate change? asks Xi Jinping. Let’s talk about what you’re going to give to get it.

Climate diplomacy czar John Kerry knows he has a problem. Taking his first swing last week, he whiffed. Mr. Kerry told the world, “The stakes on climate change just simply couldn’t be any higher than they are right now. It is existential.” He added that Mr. Biden is “totally seized by this issue.” Asked about handling China, given the many contentious disagreements, Mr. Kerry answered that “those issues will never be traded for anything” relating to climate change, which “is a critical stand-alone issue” that it is “urgent that we find a way to compartmentalize, to move forward.”

He didn’t explain how he’d compartmentalize. Nor does former Obama official John Podesta, who recently said that climate change “changes defense posture, it changes foreign policy posture” and “begins to drive a lot of decision making.” He then contradicted himself, urging Mr. Biden to build “a protected lane in which the other issues don’t shut down the conversation on climate change.” Driving down that protected lane will be interesting.

Climate adviser Gina McCarthy compounded the confusion, stressing that “we have to start shifting to clean energy, but it has to be manufactured in the United States of America, you know, not in other countries.” Her own words prove that “compartmentalization” is a fantasy. Moreover, she underscored the risk, distinctly present under Mr. Trump, that national security concerns can easily devolve into old-fashioned industrial policy.

Unfortunately for Mr. Biden, China has a vote, too. Beijing reacted quickly, criticizing Secretary of State Antony Blinken’s affirmation that oppressing the Uighurs constitutes genocide. A Chinese government account tweeted: “China is willing to work with the US on climate change. But such cooperation cannot stand unaffected by the overall China-US relations. It is impossible to ask for China’s support in global affairs while interfering in its domestic affairs and undermining its interests.” In response, Mr. Blinken repeated Mr. Kerry’s compartmentalization mantra.

China’s Asian neighbors worry about the consequences if the U.S. makes climate its priority. There are many reasons why climate change should rank lower than the Biden administration puts it. Plenty of us still believe that wind turbines don’t rise to the level of intercontinental ballistic missiles as a national security concern.

Beijing will obfuscate the stakes and trade-offs of its demands. Mr. Xi won’t propose substantially reducing carbon emissions in exchange for Mr. Biden recognizing the mainland’s sovereignty over Taiwan. But Chinese planners are certainly contemplating how to slice and dice their policy choices to achieve precisely that and other objectionable goals more subtly. Beijing’s negotiators could, say, be stubborn about climate-change issues with Mr. Kerry until Uighur sanctions are scaled down—then stay stubborn until the U.S. acknowledges Chinese sovereignty over the South China Sea.

It isn’t enough to say that closer cooperation with the European Union will increase American bargaining leverage with China. In recent months, the German-led EU has been thoroughly accommodating Beijing on both trade and strategic issues, such as the threat Huawei poses to 5G telecommunications. For now, teaming up with a limp-wristed EU could leave America in a squeeze between China and our purported allies.

Nor can America ignore its Asian friends. India will resist greater global climate-change regulation and any weakening of America’s posture on China. Japan may be closer to Mr. Biden on climate, but it opposes significant concessions on security. Taiwan will be justifiably nervous for four years. Southeast Asia and Australia also have critical interests, which they won’t cast aside lightly.

Success on climate change and China won’t be as easy as the Biden administration may imagine.