This article appeared in The Washington Examiner on March 29th, 2022. Click here to view the original article.

President Joe Biden has again befuddled America and its allies. Biden not only advocated Russian President Vladimir Putin’s removal from power — until, that is, administration aides quickly “clarified” that he wasn’t doing so.

No, there’s more.

Last Thursday, a reporter asked why sanctions decided at NATO’s Brussels summit would make Putin change course when deterrence had failed before. Biden snapped back, “Let’s get something straight. You remember, if you’ve covered me from the beginning, I did not say that in fact the sanctions would deter him. Sanctions never deter. You keep talking about that. Sanctions never deter.” Last month, the White House had to explain away similar presidential remarks about deterrence.

Biden’s confusion is dangerous, given Russian threats throughout the former Soviet Union, Chinese assertiveness in the Indo-Pacific region, and the growing nuclear menace of Iran and North Korea. Notwithstanding Biden’s incoherence, we are desperately lacking in the contemporary theory and practice of deterrence. This functioning deterrence was critical to staving off nuclear hostilities in the Cold War and, in fact, significantly debilitated the Soviet Union.

Today, for example, even top-ranking Pentagon officials refer to “restoring deterrence” merely by tit-for-tat retaliation, not realizing that deterrence is most effectively established by imposing higher costs on an enemy than it inflicted. The post-1945 study of nuclear deterrence was intense. The West’s eventual Cold War victory obscures how dangerous and uncertain those decades were, the outcome hardly inevitable. Enormous amounts of hard work, study, and debate about deterrence were required in universities and institutions such as RAND. These were not mere ivory-tower affairs. Edward Teller, Thomas Schelling, Albert and Roberta Wohlstetter, Charles Hitch, Roland McKean, Herman Kahn, and others were key figures in the contentious debate over how to avoid nuclear wars — or fight and win them if necessary.

That was only the tip of the iceberg of research and writing undertaken year after year. Analysis covered very detailed and specific concerns, assessing not just the numbers and destructive capacities of nuclear weapons but how to deliver them, such as bombers, ground-based missiles, submarine-launched missiles, or all three, where to deploy the delivery systems, whether defenses against nuclear attacks were possible and how, the costs and relative values of nuclear capabilities versus conventional forces, the nature and culture of the Soviet Union and its leadership, civilian and military, the kinds of conflicts where nuclear options could be viable, and much more.

However, since the Soviet collapse, during and after the “peace dividend” euphoria, the study of nuclear deterrence and deterrence generally declined precipitously. We are now paying the price. In Ukraine, Biden obviously failed to deter Putin — and perhaps didn’t think he could. America’s credibility was weakened because of failures to follow through on early threats and commitments, such as Georgia in 2008, Ukraine in 2014, and Afghanistan. Biden then mistakenly, gratuitously ruled out the use of U.S. force in early December 2021, with no reciprocal gestures from Russia.

No other Western leader stepped up, although many options were available that, if undertaken, could have established sufficient deterrence to prevent the invasion. The problem is now worse: Moscow is deterring Washington and intimidating the Western alliance from doing more to halt and defeat Russia’s attack. Ukrainian bravery and Russian incompetence may yet produce results favorable to Kyiv, but if that happy day comes, we should not delude ourselves that it was any more inevitable than the Cold War’s outcome.

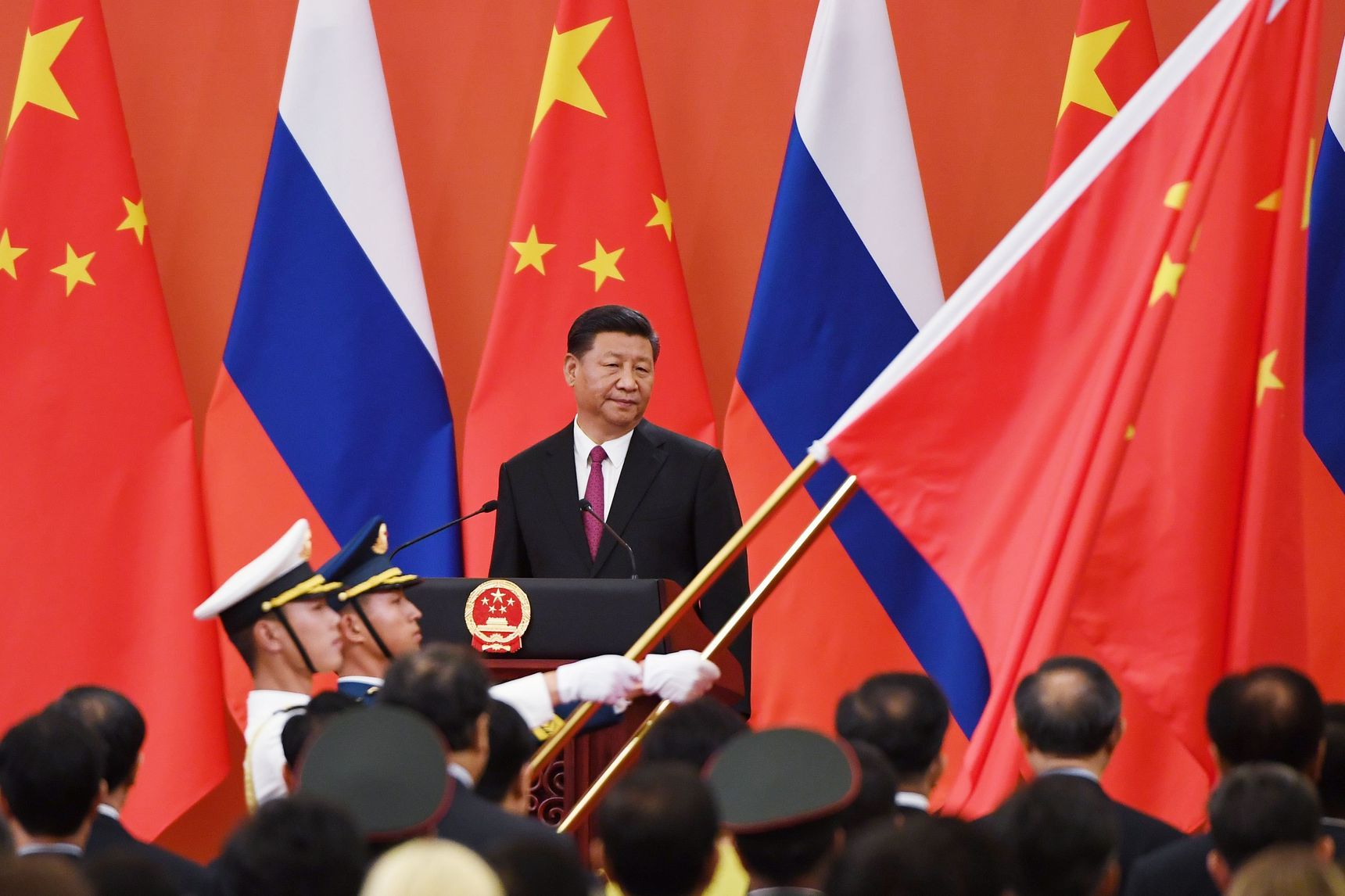

Quite the contrary. Without a doubt, China is attentively watching all aspects of the Ukraine war and its consequences for Beijing’s hegemonic aspirations on its periphery. Taiwan is the most endangered but not the only target in Beijing’s sights. Ukraine is more than ample advance warning that our deterrence thinking is tired, trite, and inadequate.

We urgently need not just a contemporary version of the Cold War Kremlinology and intelligence we had on the Soviet Union. We need China-specific deterrence theory and analysis, and we need it immediately and compellingly for Taiwan. Specific suggestions for Taiwan abound, including ending “strategic ambiguity,” placing U.S. military forces on Taiwan, and diplomatic recognition, but we haven’t yet found Taiwan’s Teller or Schelling. China’s nuclear, not to mention chemical and biological, weapons capabilities will be critical elements of new deterrence theory and practice, but deterring conventional warfare also needs far more creative thinking. Warfighting strategies are changing rapidly as asymmetrical and hybrid variations evolve. Cyberwarfare is still in its relative infancy, and we have no deterrence theory comparable to Cold War nuclear theory.

Obviously, enormous work has been done regarding possible conflicts with China. But within America’s political class, marrying that work with deterrence theory and practice is nowhere near adequate. Time is short.

John Bolton was the national security adviser to former President Donald Trump between 2018 and 2019. Between 2005 and 2006, he was the U.S. ambassador to the United Nations.