Recent reports that the Trump administration is withholding roughly $400 million of military assistance to Taiwan are deeply disturbing. Although the White House maintains no final decisions have been made, the pause is eerily similar to Trump’s summer 2019 withholding of security assistance to Ukraine, for reasons entirely unrelated to Kyiv’s defense needs.

China’s threat to Taiwan is beyond dispute. Congressional support for aiding Taiwan militarily, and thereby hopefully deterring Beijing’s aggressive intentions, remains firm and fully bipartisan — highly compelling in an otherwise highly partisan, politicized Washington. If anything, the principal criticism of Taipei’s national security efforts since the Taiwan Relations Act of 1979 is that they have been insufficient, although those criticisms are now badly outdated.

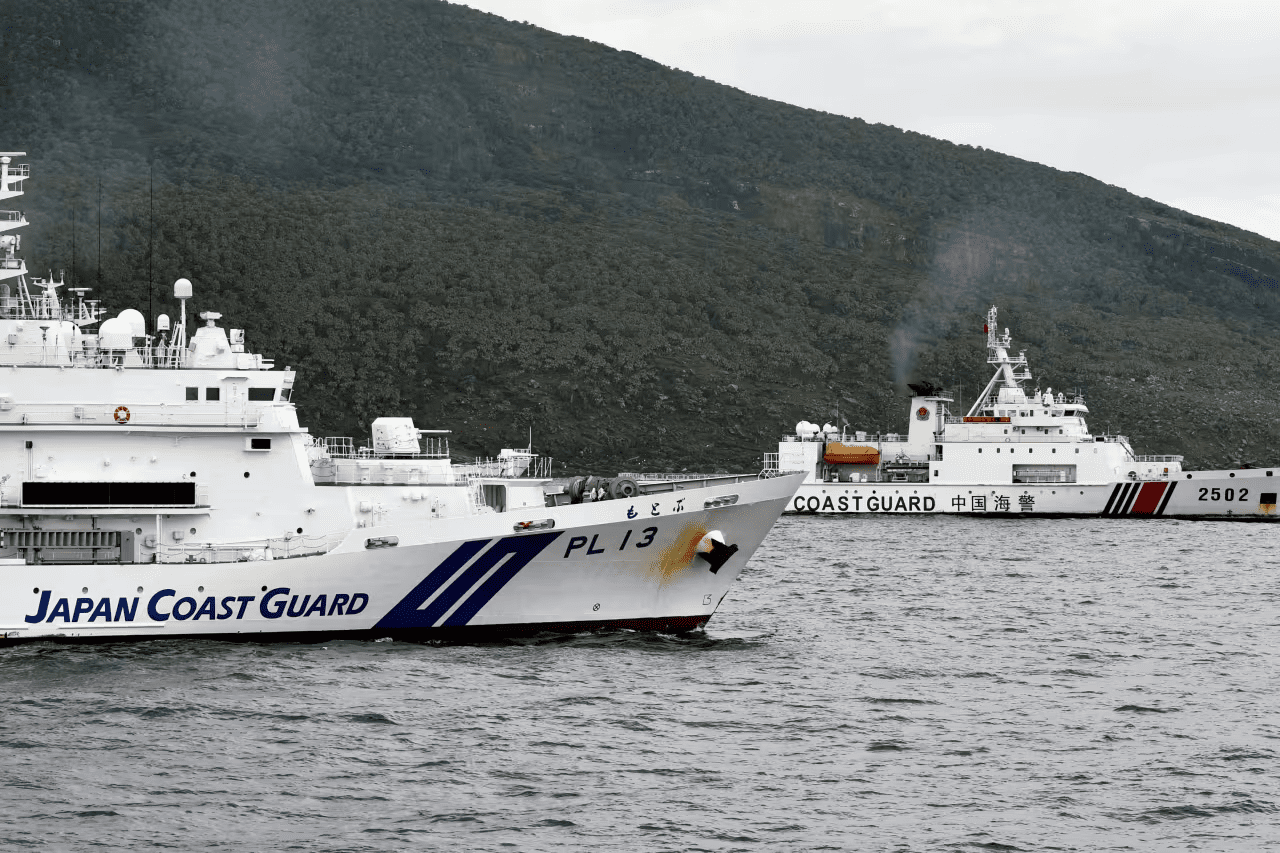

Unfortunately, the case for America’s interest in Taiwan’s self-defense and de facto independence has long been less than clearly stated. Since 1949, the United States has been vitally interested in preventing Taiwan from being swallowed by the mainland Peoples Republic of China. Taiwan’s critical geographic location in the “first island chain” between China and the open Pacific, an island once prompted Douglas MacArthur to call it “an unsinkable aircraft carrier.” Taiwan’s economic importance and its vibrant, constitutional, representative government also underline its centrality to U.S. national security.

That is why the reported halt in military assistance is so troubling. The apparent reason for the arms cutoff is Trump’s obsession with a trade deal with China and his palpable hunger for a summit with Xi Jinping. In his first term, Trump spoke repeatedly of making “the biggest trade deal in history” with China, which he failed to do. Today, reaching a China deal is significantly harder because of the incoherent, worldwide “reciprocal” tariffs he promulgated this spring, which deny Washington numerous potential allies in blocking China’s deeply invidious trade policies.

On Sept. 19, Xi and Trump spoke to discuss several issues, including the status of Tik Tok. As with his overall kid-glove treatment of Beijing, Trump has defied clear statutory deadlines to shut Tik Tok down or else sell it to new owners with assurances that it will no longer vacuum up American users’ information. Trump’s initial opposition to Tik Tok’s espionage threat disappeared when he concluded that it boosted his re-election campaign, and the ownership interests of several key supporters.

Taiwan has long feared Trump might trade away its interests in pursuing mega-trade arrangements with the Chinese communists. There is already ample evidence, beyond arms-supply issues, that he is going out of his way to placate Beijing.

Since Russia’s aggression against Ukraine, China has been, by a considerable margin, the largest international purchaser of its oil and gas. Nonetheless, despite threating rhetoric, Trump has imposed no additional tariffs or secondary sanctions on China.

In contrast — India, a clear strategic priority for Washington to constrain Beijing’s hegemonic ambitions — has been hit with 25 percent U.S. tariffs on top of 25 percent “economic” tariffs. This burdens Indian exports to the U.S. by 50 percent, a level far higher than other trading partners.

And despite Russia’s s clear disdain for his proposals to stop the Ukraine war, Trump has rejected new sanctions on Russia. He has, in fact, conditioned such action on European nations hitting India and China with significant tariff increases. Whatever Trump’s motives, the net effect is to spare both Moscow and Beijing.

Taiwan is America’s seventh-largest trading partner and the world’s key manufacturer of sophisticated computer chips, which underlines the enormous risk of mainland Chinese hegemony over the island. But what troubles Taiwan most deeply is the risk of political concessions. If, for example, Trump agreed to revise the Shanghai Communique (or even reinterpret it unilaterally) to concede communist China’s sovereignty over Taiwan, it would gravely compromise Taiwan’s political viability. Asian governments especially would see such a concession (or lesser versions of it) as Washington effectively abandoning Taipei to Beijing’s tender mercies.

A radical restatement of the U.S. position on Taiwan could well violate the commitments to support Taipei’s defense that were legislated in the Taiwan Relations Act and undoubtedly cause a political firestorm in Congress. Of course, as the Tik Tok case demonstrates, Trump ignores statutes he dislikes, and Congress remains quiescent. Violating the Taiwan Relations Act might seem easy for an emboldened Oval Office occupant. It would unquestionably incentivize Xi to increase his squeeze on Taiwan.

This is no time for Taiwan’s supporters to be passive. Taiwan could be cast adrift at a moment’s notice. In Trumpworld, posts on social media, government by whim, are the preferred medium of communications, all too often without considered analysis by the National Security Council, let alone close consultations with allied governments.

Whether Trump can negotiate the biggest trade deal in history is problematic. Even more problematic is whether China would deign to adhere to any “commitments” it might make. The U.S. should urgently restore the suspended military assistance and make clear that Beijing will not rule Taiwan any time soon.

This article was originally published in The Hill, on September 24, 2025. Click here to read the original article.