This article was first published in The Hill on May 5, 2023. Click Here to read the original article.

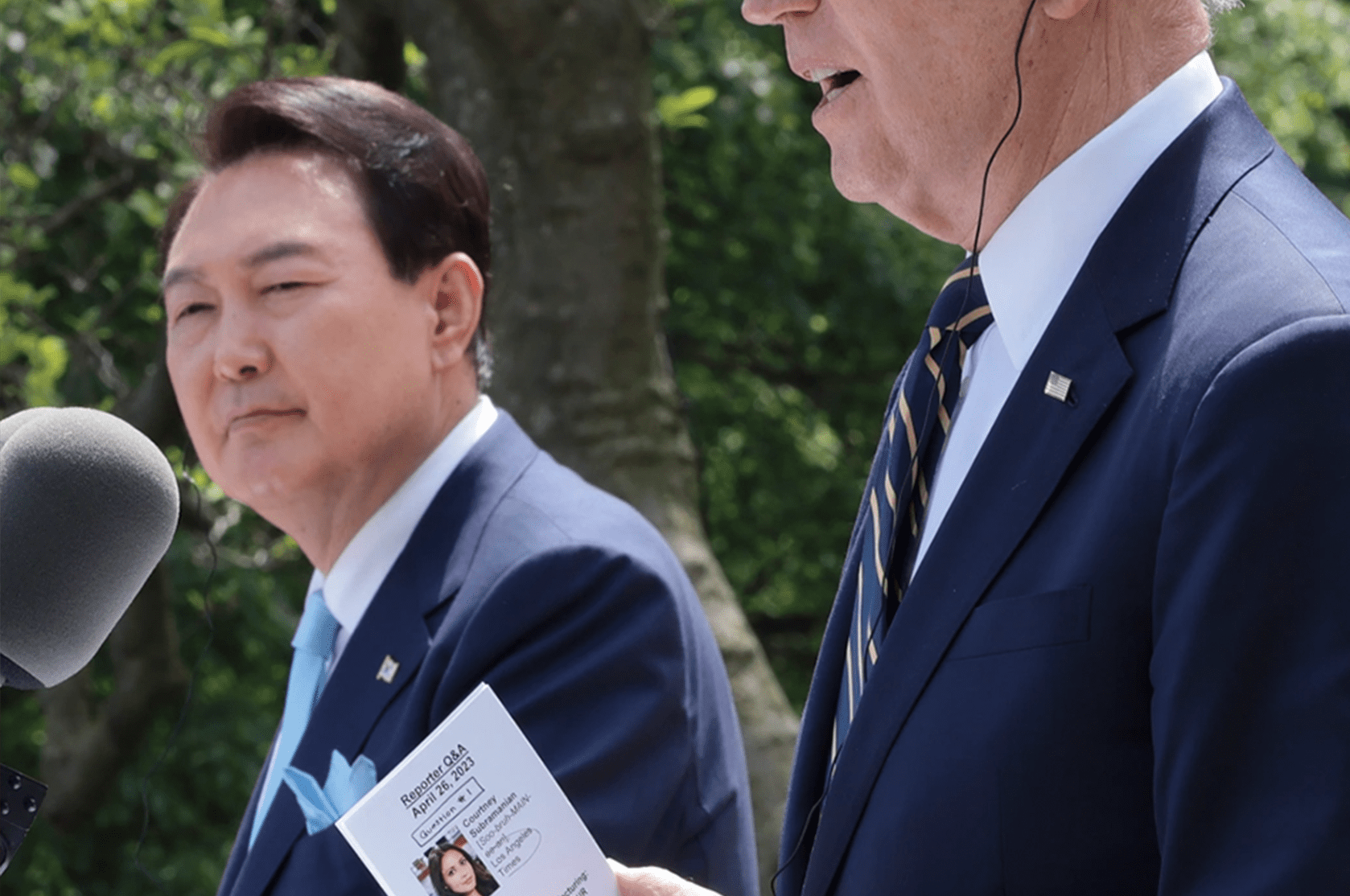

Last week’s summit between President Biden and President Yoon Suk-yeol of the Republic of Korea (“ROK”) had a full agenda, but there is little doubt that Yoon’s top priority was the omnipresent, growing North Korean nuclear threat.

Unfortunately, the celebration of the ROK-U.S. alliance’s 70th anniversary produced a joint statement, the Washington Declaration, that fell far short of what was necessary.

The Declaration’s modest measures will not slow Pyongyang’s efforts to reunite the Peninsula under its control, so tensions in Northeast Asia will almost certainly continue rising.

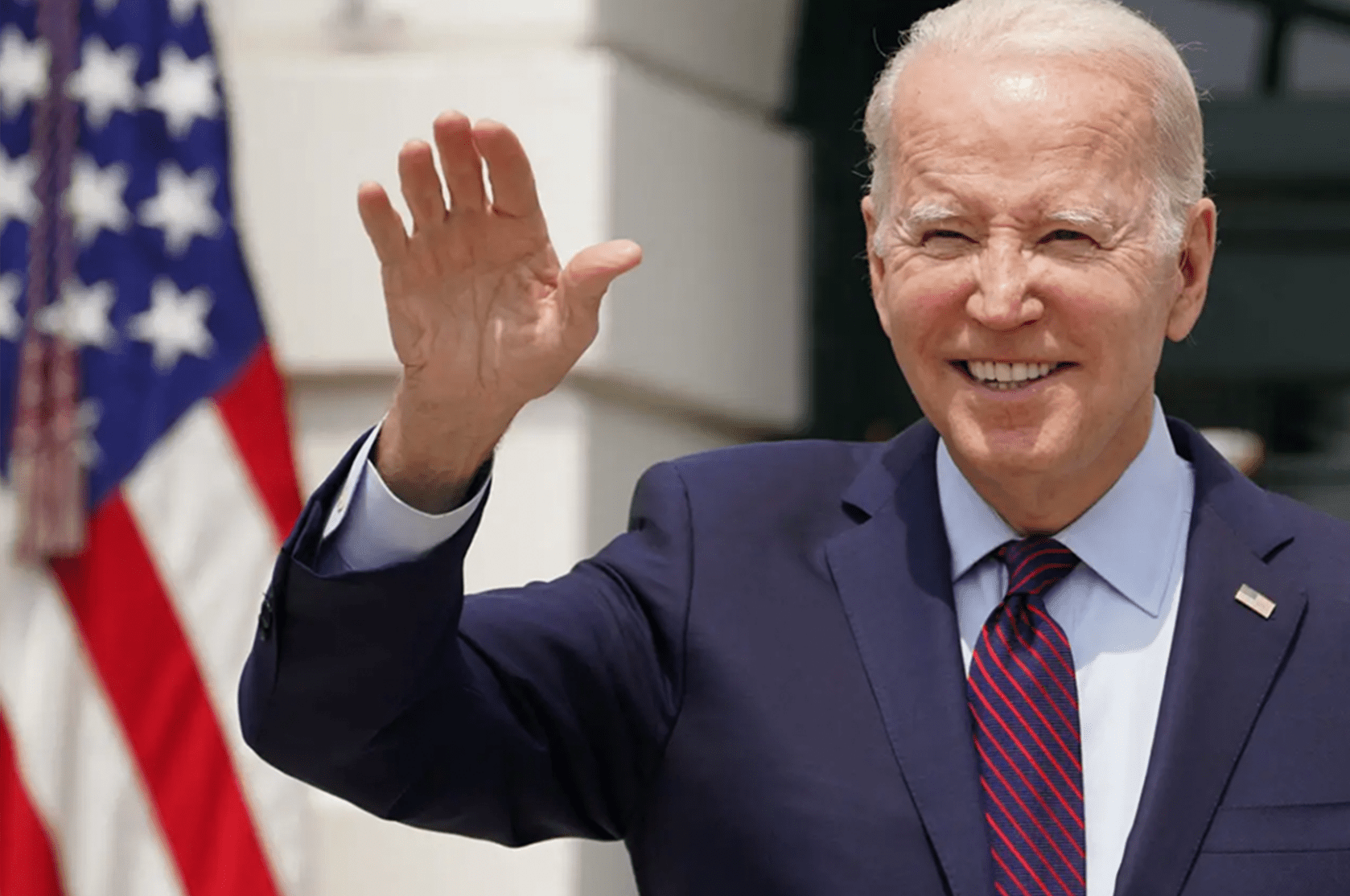

Reflecting a growing fear that America’s nuclear “extended deterrence” is no longer reliable, either against the North or, importantly, China, South Korean public opinion has increasingly supported an independent nuclear program.

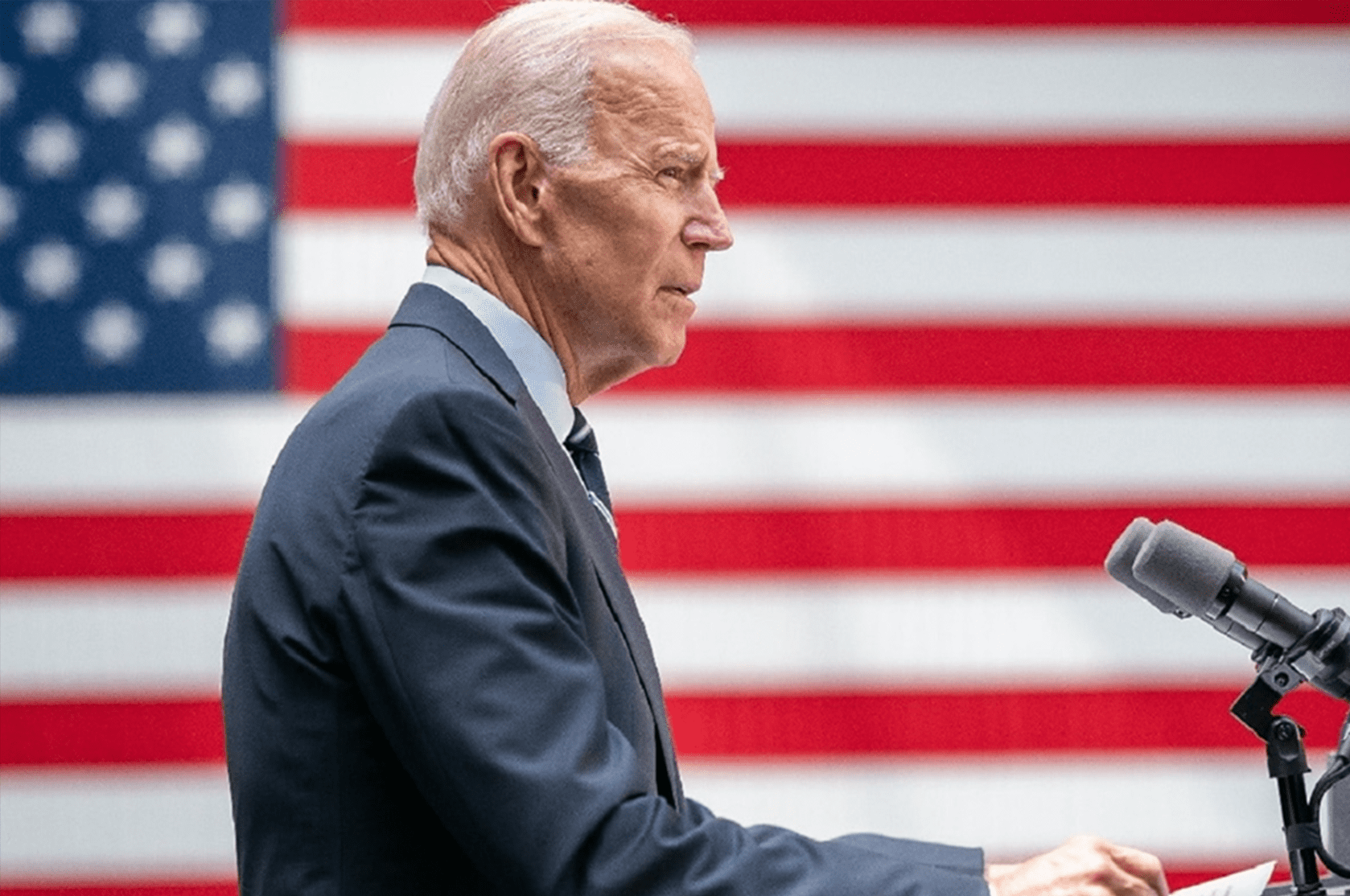

Biden’s response to Beijing’s and Pyongyang’s growing nuclear and ballistic-missile threats, embodied in the Declaration, will do little to alleviate these ROK concerns.

The most palpable new U.S. commitment to opposing North Korean belligerence is that our nuclear ballistic-missile submarines will, for the first time in 40 years, resume docking, occasionally, in South Korea. Anonymous U.S. officials also predicted there would be a “regular cadence” of visits by aircraft carriers, bombers and more.

Did the White House really believe Pyongyang’s leadership thought America’s nuclear arsenal was imaginary? Perhaps. It’s a strange leadership, with strange ideas, so parading the cold steel from time to time might have an effect, if not on China’s Xi Jinping, perhaps on North Korea’s Kim Jung Un.

Far more likely, however, is that neither Kim nor Xi doubt Washington has massive nuclear assets. Instead, ironically but tellingly, they, like South Korea’s citizens, think very little of today’s U.S. leadership, Republican or Democratic.

China and both Koreas perceive a lack of American resolve and willpower to act decisively when ROK and U.S. national interests are threatened. If so, the Washington Declaration’s rhetoric about the U.S. commitment to extended deterrence and strengthening bilateral military ties will be seen as words, and words alone. We are kidding ourselves to believe that having “boomers” pitch up in South Korean waters sporadically will have any deterrent effect.

By contrast, redeploying U.S. tactical nuclear weapons in South Korea, effectively indefinitely, is several orders of magnitude more serious. First, these weapons would remain under sole American control, and immediately available to assist in defending deployed U.S. forces, and their Republic of Korea cohorts. “We go together” (or “katchi kapshida” in Korean) becomes much more than the combined forces’ long-standing slogan when backed by battlefield nuclear capabilities. That is far more palpable than submarine port calls.

Second, tactical nuclear deployments would give heft to the Washington Declaration’s creation of the Nuclear Coordination Group (“NCG”), charged with strengthening extended deterrence, discussing nuclear planning and managing North Korea’s proliferation threat. The new NCG would be far more than just another bureaucratic prop if it had real-world questions like optimizing the deterrent and defensive value of tangible nuclear assets. Lacking concrete responsibilities, how will the new NCG differ from the existing Extended Deterrence Strategy and Consultation Group, and others, which the Declaration says will be “strengthened”?

Third, while the issue of an independent ROK nuclear capability is politically and militarily separate from returning American tactical nuclear weapons to the Peninsula, renewed deployment would nonetheless buy valuable time for Seoul and Washington to evaluate fully the implications of South Korea becoming a nuclear-weapons state. The presence of American nuclear assets on the Peninsula neither precludes nor renders inevitable a separate ROK program, which has the further advantage of keeping Beijing and Pyongyang guessing.

Moreover, the implicit message weakening the Washington Declaration is that America’s antiproliferation efforts to stop Pyongyang from becoming a nuclear power have failed. Consider the proliferation aspect of the NCG’s mandate: it is to “manage” the North Korean threat. Not “defeat” that threat, not “eliminate” or “end” that threat, but merely “manage” it.

This is the language of bureaucrats, not statesmen, and it sounds suspiciously like giving up on working to prevent North Korea from becoming able to deliver nuclear payloads.

It is therefore appropriate to emphasize that those who opposed taking decisive steps against nuclear proliferators like North Korea and Iran long argued that we had ample time for negotiations. Accordingly, they said, efforts at regime change or pre-emptive military action were over-wrought, premature and unnecessary. Now that Pyongyang has detonated six nuclear devices, and Iran continues to progress toward its first, these same people say the rogue states are already nuclear powers, and we must hereafter rely on arms control and deterrence.

In other words, first it was too soon to take decisive action, and now it is too late. One might almost conclude that for all the posturing over the years that North Korean (or Iranian) nuclear weapons were “unacceptable,” that’s not really what many U.S. politicians and policymakers actually believed. They were prepared to accept American failure, but they knew it was impolitic to say it out loud in public. We are all now at greater risk because of this hypocrisy.

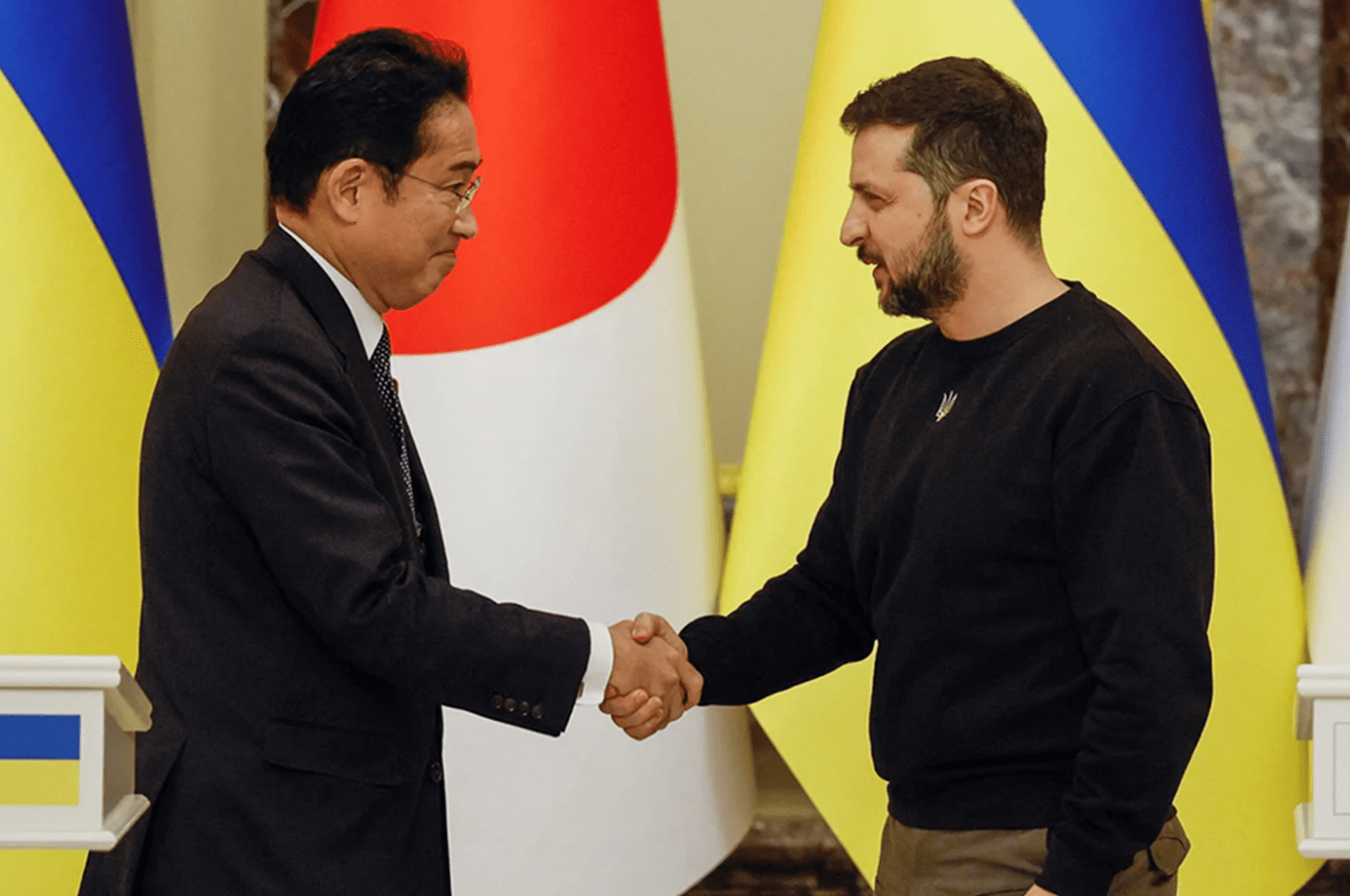

In the Indo-Pacific and the Middle East, where the menace of nuclear proliferation is all too real, others have refused to give up. In his first year in office, for example, Yoon has made improving ROK-Japan relations, badly damaged by his predecessor, a top priority. Better Tokyo-Seoul cooperation is critical to enhanced three-way efforts with Washington, and Yoon’s diplomacy with Japanese Prime Minister Fumio Kishida is paying dividends. Kishida will visit South Korea, the first such visit in five years, just before the Hiroshima G-7 meeting, to which Yoon is invited.

It’s obviously easier for Kishida to sell U.S. deployment of tactical nuclear weapons in the South than an independent ROK nuclear force, which would instantly raise in Tokyo the complex question of a comparable Japanese capability.

Biden’s half-hearted efforts to enhance U.S. national security should be a significant political vulnerability in the 2024 presidential campaign. It remains to be seen whether Republicans have the wit to make it an issue.