Two recent, seemingly unconnected events involving India highlight its growing global role. Both were largely unreported in the United States media. One involves a combined U.S.-Indian effort to counter China’s Belt and Road Initiative, or BRI, and the other is a murky Qatari prosecution of former Indian naval officers allegedly spying for Israel. Together, they demonstrate New Delhi’s steadily growing importance to Washington and underline why we should pay more attention to the world’s most populous country. Prospects for closer bilateral cooperation are plentiful and important, notwithstanding continuing different perspectives on key topics such as trade and relations with Russia.

Beyond doubt, India will be a pivotal player in containing China’s hegemonic aspirations along its vast Indo-Pacific perimeter. Moreover, India’s already considerable Middle Eastern role will inevitably grow. The ramifications for India from Israel’s current war to eliminate Hamas’s terrorism and constrain its Iranian puppet masters are significant, opening opportunities for both countries. But the situation also presents risks in a complex and difficult region.

FEDERAL COURT TO WEIGH AMTRAK BID TO TAKE DC’S UNION STATION IN EMINENT DOMAIN CASE

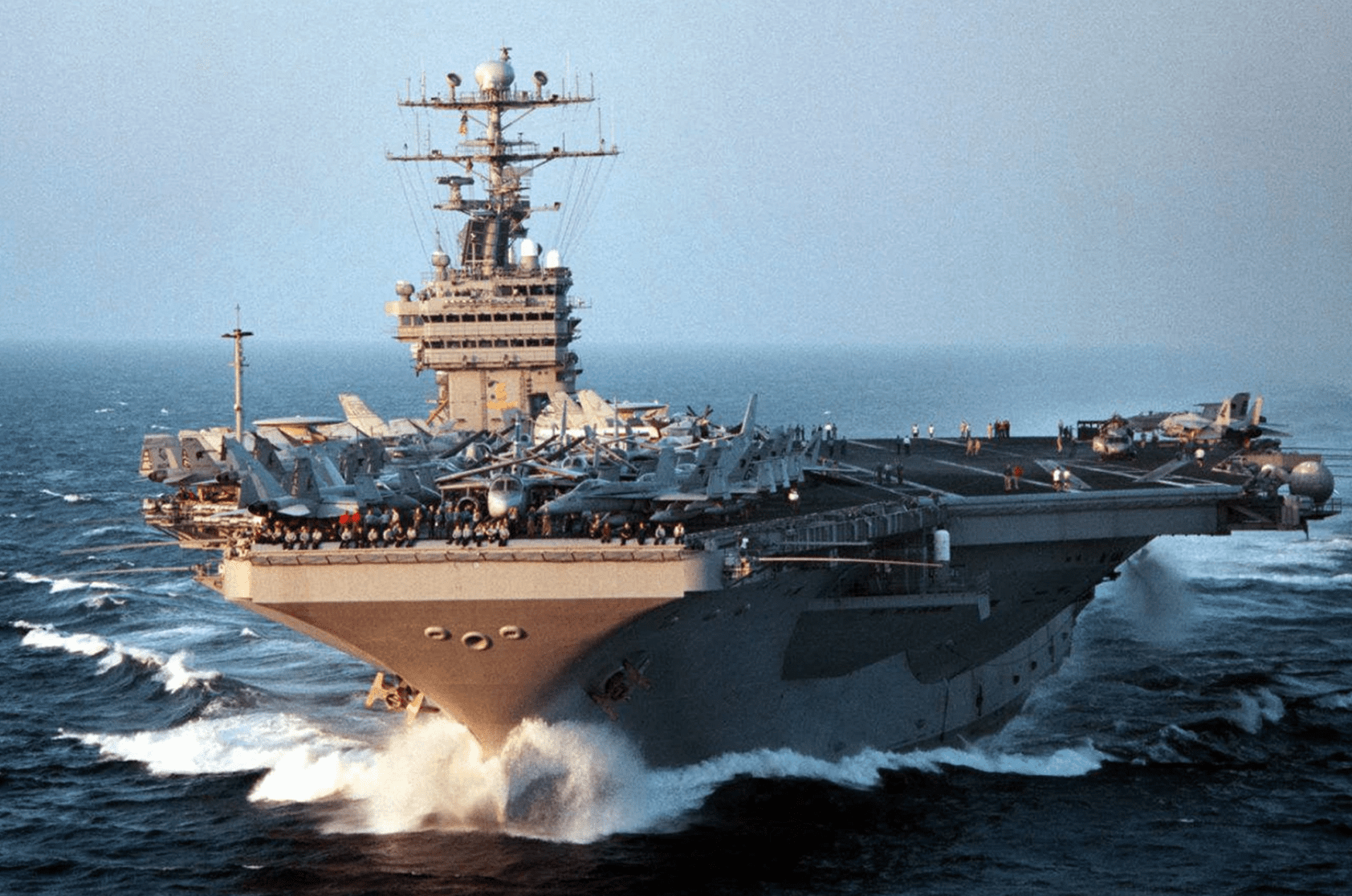

Major economic news with obvious geopolitical implications came in early November when the U.S. International Development Finance Corporation announced it would loan $553 million for a deep-water container terminal project in Colombo, Sri Lanka’s capital and largest port. The Adani Group, one of India’s biggest industrial conglomerates, with deep expertise in port construction and management, is the project’s majority owner in this the first significant cooperative effort between India’s private sector and America’s government, one directly competitive with China.

Colombo’s port was an early target of China’s BRI, a program aimed at ensnaring developing countries in complex financial arrangements for major infrastructure projects. China ultimately took full control of its port facility, which many fear will ultimately serve military purposes.

Contesting China’s economic and influence operations across the global south, especially the BRI, must be a U.S. strategic priority. Teaming with a pathbreaking private Indian firm in the Colombo venture is a dramatic example of leveraging U.S.-Indian resources to mutual advantage. The Development Finance Corporation advances American interests by financing a major project potentially benefiting U.S. firms, and thereby vividly contrasts with China’s corrupt and ultimately subversive BRI approach. Sri Lanka also gains significantly. Since the Adani project is almost entirely private sector-owned (as opposed to BRI’s government-to-government matrix), Sri Lanka’s sovereign debt will not grow. There is no guarantee that additional projects or joint ventures with the Adani Group or other Indian firms will be easy, but the template is at least now in place.

In a separate development, Qatar arrested and charged eight former Indian naval officers (doing consulting work with Qatar’s military) as Israeli spies in August 2022. The specifics are unclear, and little was heard about the men until after Hamas’s brutal Oct. 7 attack on Israel. Declaring a dramatic shift in position, India announced support for Israel’s right to self-defense, whereupon Doha revealed on Oct. 26 that the prisoners had received death sentences. India greeted this news, tied in the public mind to its support for Israel, with outrage and dismay. Ironically, New Delhi had been trying to increase defense cooperation with Doha, and approximately 600,000 of its citizens work in Qatar (out of Qatar’s total population of about 2.5 million). India has insisted that Qatar release the men or at least commute their sentences; Qatari legal proceedings to that end are now underway.

Qatar has a lot riding on finding the right answer on the Indian prisoners, especially given the current war against Israel. Moreover, Qatar will not want to disrupt the promising initiative, announced at this year’s G20 meeting to link South Asia, the Middle East, and Europe more closely together through an “Economic Corridor.” In some ways, more is at stake here for Doha than for New Delhi. With China’s population declining, its internal socioeconomic problems growing, and its place in the world declining steadily relative to India’s, this is no time for Qatar to stay on board a sinking ship. India’s already voluminous demand for oil will only grow, while China’s will shrink as its economy slowly declines.

The Qatar-India imbroglio could figure significantly in U.S. efforts to counter the China-Russia axis (including its outliers such as North Korea, Iran, and Syria) in the Middle East and South Asia. Washington cannot by itself end tensions among the Gulf’s oil-producing Arab states, nor can it resolve all disagreements between the Gulf monarchies and the wider world. But America is hardly indifferent to regional dynamics, especially those weakening the common front against Iran’s support for international terrorism and its nuclear weapons and ballistic missile programs.

Just as the Adani Group’s Colombo port project, bolstered by U.S. financial connections, is geostrategically important to counter China’s hegemonic aspirations, so is increasing greater unity among America’s Arab partners. A wider Indian role and cooperation with the U.S. globally will serve both countries’ national interests.

This article was first published in The Washington Examiner on December 1, 2023. Click here to read the original article.