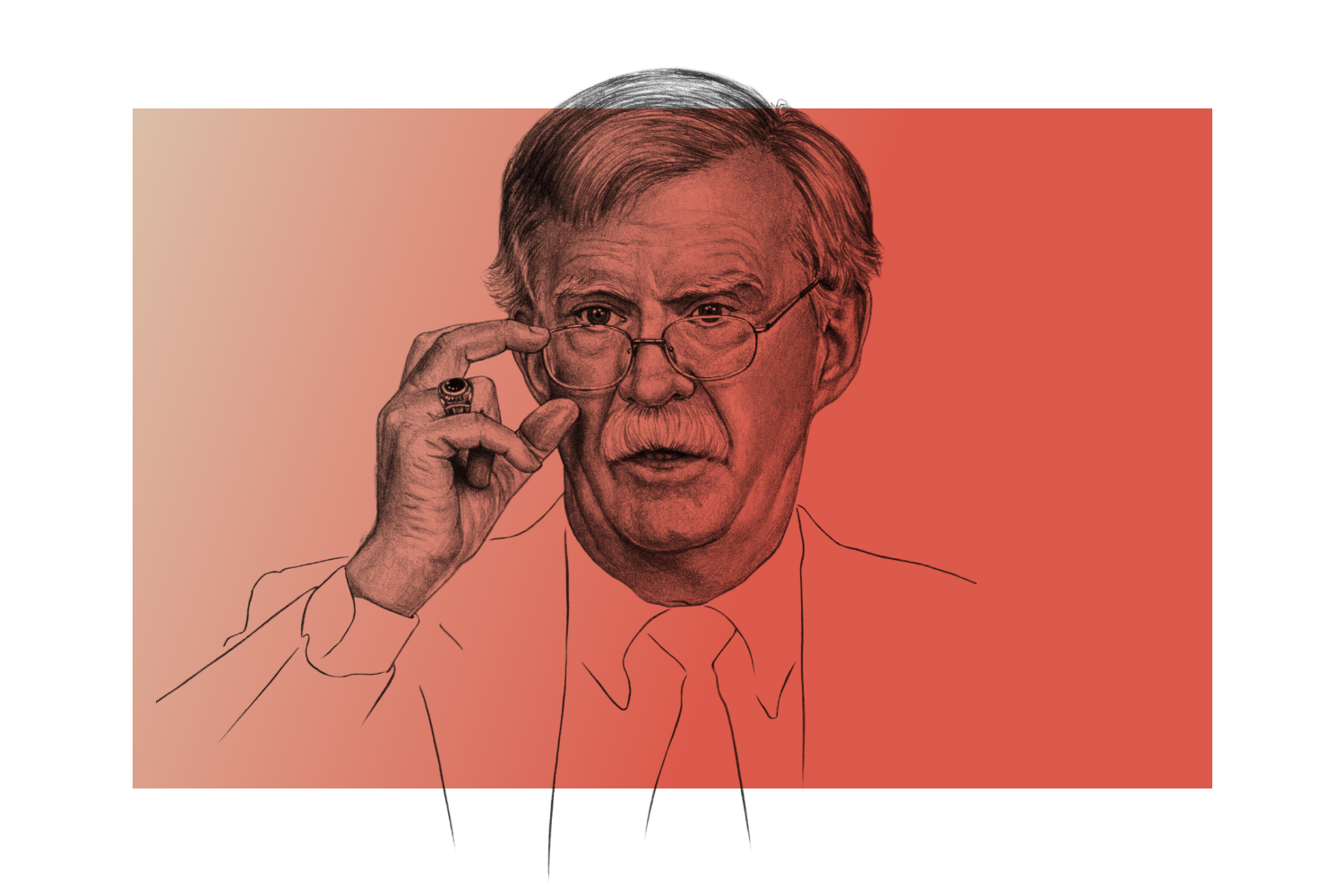

John Bolton was once the enfant terrible of the Republican Party. Is he now its conscience?

This article was first published in Foreign Policy on February 6th, 2023. Click Here to read the original article.

John Bolton is worried about a virus but probably not the one you’re thinking of. The former U.S. national security advisor arrives for lunch at Edgar Bar & Kitchen in the Mayflower Hotel in Washington carrying a long umbrella and a 5,000-word printout of an essay he had written over the holiday break for the National Review. The subject of his cri de coeur? The “virus of isolationism” that has gripped the fringes of his beloved Republican Party.

Like the restaurant’s namesake—J. Edgar Hoover, the FBI’s first director, who dined at the hotel on a daily basis—Bolton is a regular. The seat at the back corner, in front of a shelf of Prohibition-era liquor bottles, is his usual spot, the hostess informs me. There is a frisson of excitement among the servers, who evidently know who he is. Shortly before Bolton’s arrival, a Secret Service agent with a discreet coiled earpiece sweeps by, a reminder of the Iranian bounty on his head. “I was offended that they only offered $300,000,” Bolton says when I ask him about it later, before wondering aloud if the price had gone up now that he has a security detail.

Bolton has long served as the id of the Republican Party, happy to say the quiet part out loud on cable news and in the op-ed pages of national newspapers. He has advocated for the bombing of North Korea and Iran, joked on CNN about plotting coups, and most recently called for Turkey to be ejected from NATO.

He joined the White House in April 2018 as then-President Donald Trump’s third national security advisor, at the point when any illusions that the weight of the office would cause Trump’s better angels to prevail had been long since banished. Seventeen months later, he was out—fired or resigned, as Bolton has claimed—as the relationship soured. While much of the Republican Party continues to turn on the Trump axis, Bolton has broken with his former boss in a dramatic fashion. Many of his peers have contorted themselves to fit the MAGA mold or slunk from the limelight altogether, but Bolton has kept on Boltoning. Now, as the Republicans take the gavel in the House of Representatives and Russia’s war in Ukraine approaches its first-year anniversary, I invited Bolton to lunch to find out what one of the party’s foremost hawks makes of recent calls from Republicans to curb U.S. support to Kyiv.

We meet in early January as Congress is on its sixth—or maybe seventh or eighth or ninth—vote for House speaker as Kevin McCarthy battles a handful of rebels from within his own party. Bolton dismisses the spectacle unfolding on the House floor with trademark alacrity. “I don’t think it’s an ideological division,” he says, “so much as it is between people who may have diverging views but are serious about governing versus people for whom politics has become performance art.”

It’s not that group’s willingness to buck consensus that seems to bother him the most but the hollowness of their position. “If one of the isolationists would stand up and make the case that assisting Ukraine is not in the strategic interest of the United States, then you could at least have a discussion, but that’s not what they do.”

Bolton refused to testify during Trump’s first impeachment hearing, but it was the former president’s declaration that the U.S. Constitution should be terminated that prompted Bolton to throw his hat into an ever-expanding ring of Republican hopefuls weighing a 2024 bid for the White House. “Donald Trump is unacceptable as a Republican nominee,” he said on NBC’s Meet The Press in December. “I had not intended to [run] until Trump came out with his comment,” Bolton tells me.

One of the presumed 2024 candidates with whom Bolton seems most comfortable is the one who has most often been described as Trump’s heir apparent, Florida Gov. Ron DeSantis, whom Bolton has known since 2012. “I’ve watched him very carefully. I’d feel very comfortable with his foreign policy.”

Bolton is something of a nerd, and true to form, while we wait to order our salads, he offers a potted history of the restaurant, and we get onto the topic of the Mayflower’s cameo in many a Washington spy scandal. This leads us to one of his latest book acquisitions, Cloak and Gown by Robin Winks, about the secret history between academia and the intelligence agencies during World War II and the early years of the Cold War.

Whether it’s just his nature or experience born out of years of talking to journalists, Bolton offers compact, to-the-point answers to my questions, distinguishing himself from many a voluble Washington denizen of his tenure. Maybe that’s why he feels the need to justify the length of his essay on isolationism. “My feeling has been that I needed to write all this out. So that’s why it’s 5,000 words long,” he says.

It’s unclear how many Republicans who have questioned military aid to Ukraine would sit down to read such a treatise on U.S. foreign policy. But Bolton got his start in a different era. During his five decades in Washington, Bolton has served in four Republican administrations, holding positions at the Justice Department, State Department, and U.S. Agency for International Development during the Reagan and George H.W. Bush administrations. Through those various stints in office, he enjoyed many wrestling matches with the bureaucrats. In an era of spicy tweets, dubious facts, and 30-second cable news sound bites, though, I can’t help but wonder if Bolton is bringing a knife to what is now a gunfight.

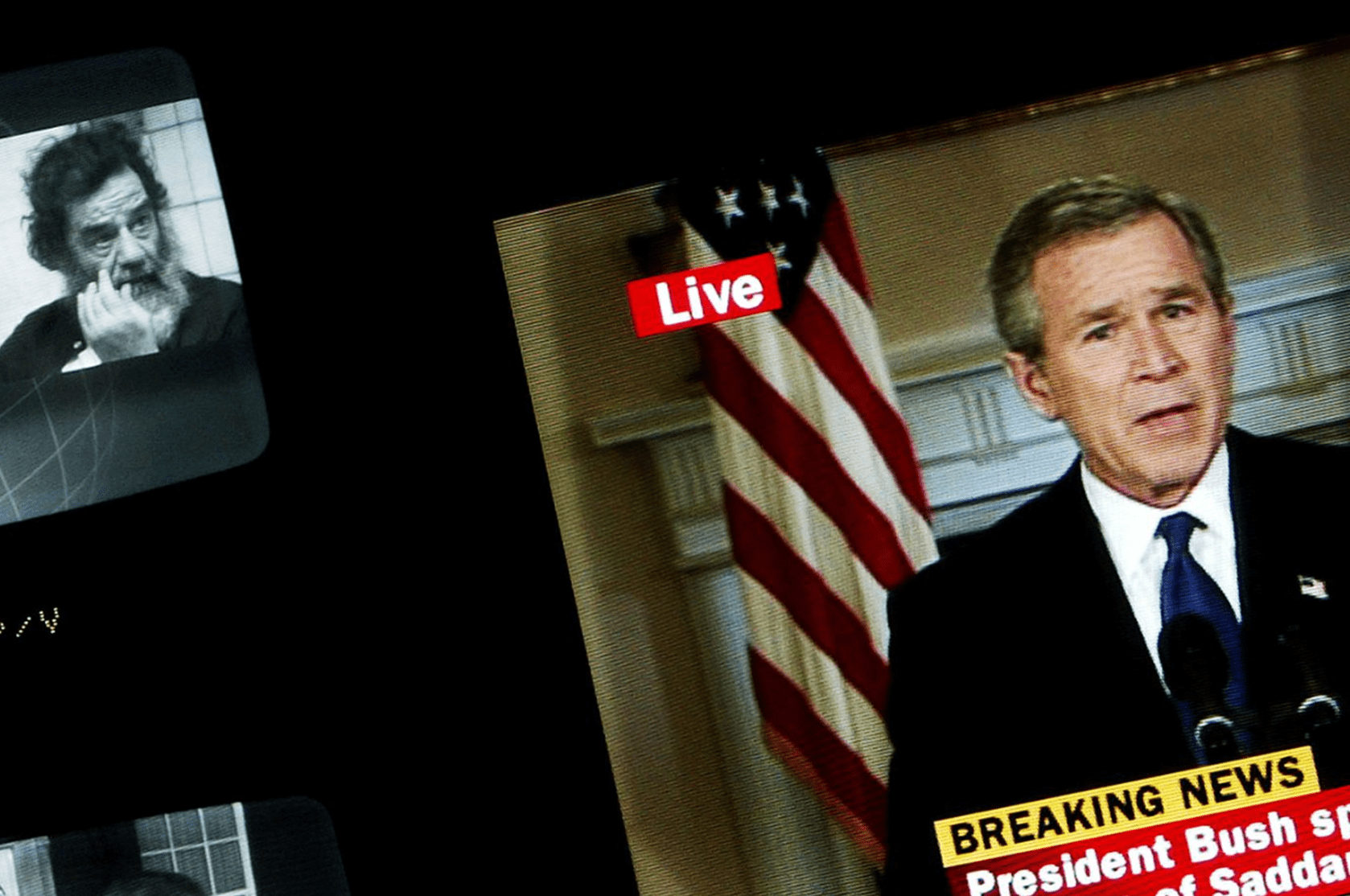

It was during his tenure as undersecretary of state for arms control and international security in George W. Bush’s first term that Bolton was dubbed “human scum” and a “bloodsucker” by North Korean state media. That came after he delivered a speech in which he described North Korean leader Kim Jong Il as a “tyrannical dictator.” He would later describe the moniker from Pyongyang as the “highest accolade” he had received during his time in the junior Bush’s administration.

During Senate confirmation hearings for his nomination to serve as Bush’s ambassador to the United Nations in 2005, an altogether more serious series of claims were made—that Bolton had sought to cherry-pick intelligence and bullied analysts who challenged his conclusions. Bolton was a “kiss-up, kick-down” sort of guy, the former head of the State Department’s in-house intelligence bureau, Carl W. Ford Jr., told the Senate Foreign Relations Committee. Bolton denied the allegations, but his nomination stalled, and he was ultimately sent to the United Nations as a recess appointee.

Bolton does not seem to mind and perhaps even revels in his reputation as the enfant terrible of the Republican Party. I ask him how he would describe his role within the ecosystem of the party, but the man who has been called all sorts of things says he is not a fan of labels. “I don’t like these bumper stickers, this taxonomy of trying to put people in boxes,” he says.

In August 2022, the Justice Department revealed that it had charged an Iranian man with plotting to have Bolton assassinated. This was in apparent retaliation for the U.S. drone strike at the beginning of 2020 that killed Iranian commander Qassem Suleimani. Bolton was first alerted of the plot in early 2021. He was called into FBI Headquarters shortly before Thanksgiving that year to be warned that the threat had become more specific.

“‘If this threat were because of my op-eds and speeches, I would be flattered, but I don’t think that’s what it is. I think it’s what I was doing in the government,’” he recalls telling the room of 15 or so investigators, before suggesting that it was perhaps incumbent on the government to therefore to do something about it. “They said, ‘Have you called the Biden White House?’ And I said, ‘Are you crazy? Of course I haven’t called the Biden White House. Why don’t you call the Biden White House?’” Shortly afterward, President Joe Biden signed an order providing Bolton with Secret Service protection.

Although Bolton’s service in the Trump White House follows him quite literally these days—in the form of a security detail—he is eager to distance himself from the former president. In fact, in diagnosing the resurgence of isolationism within the Republican Party, Bolton points to Trump as patient zero.

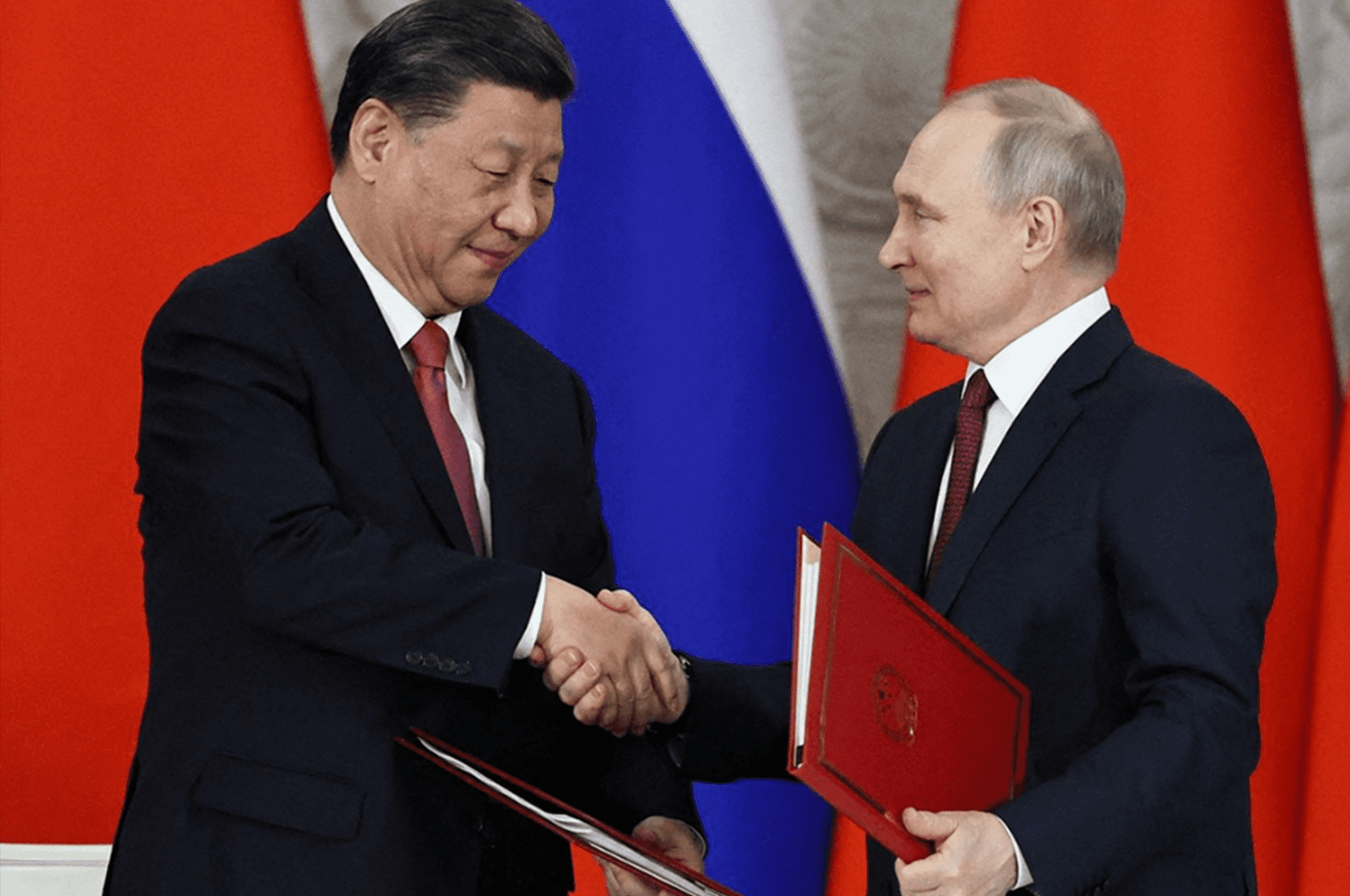

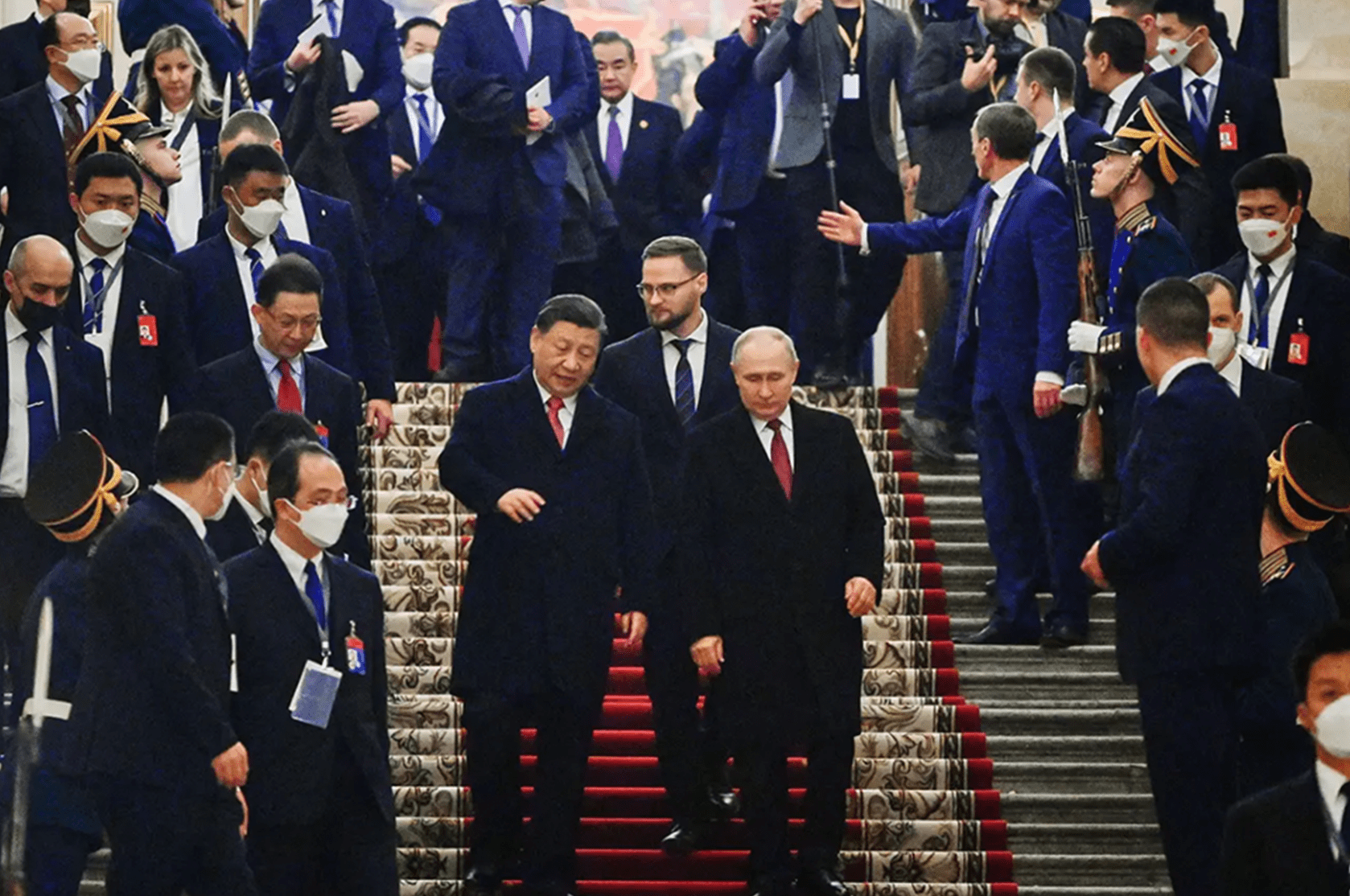

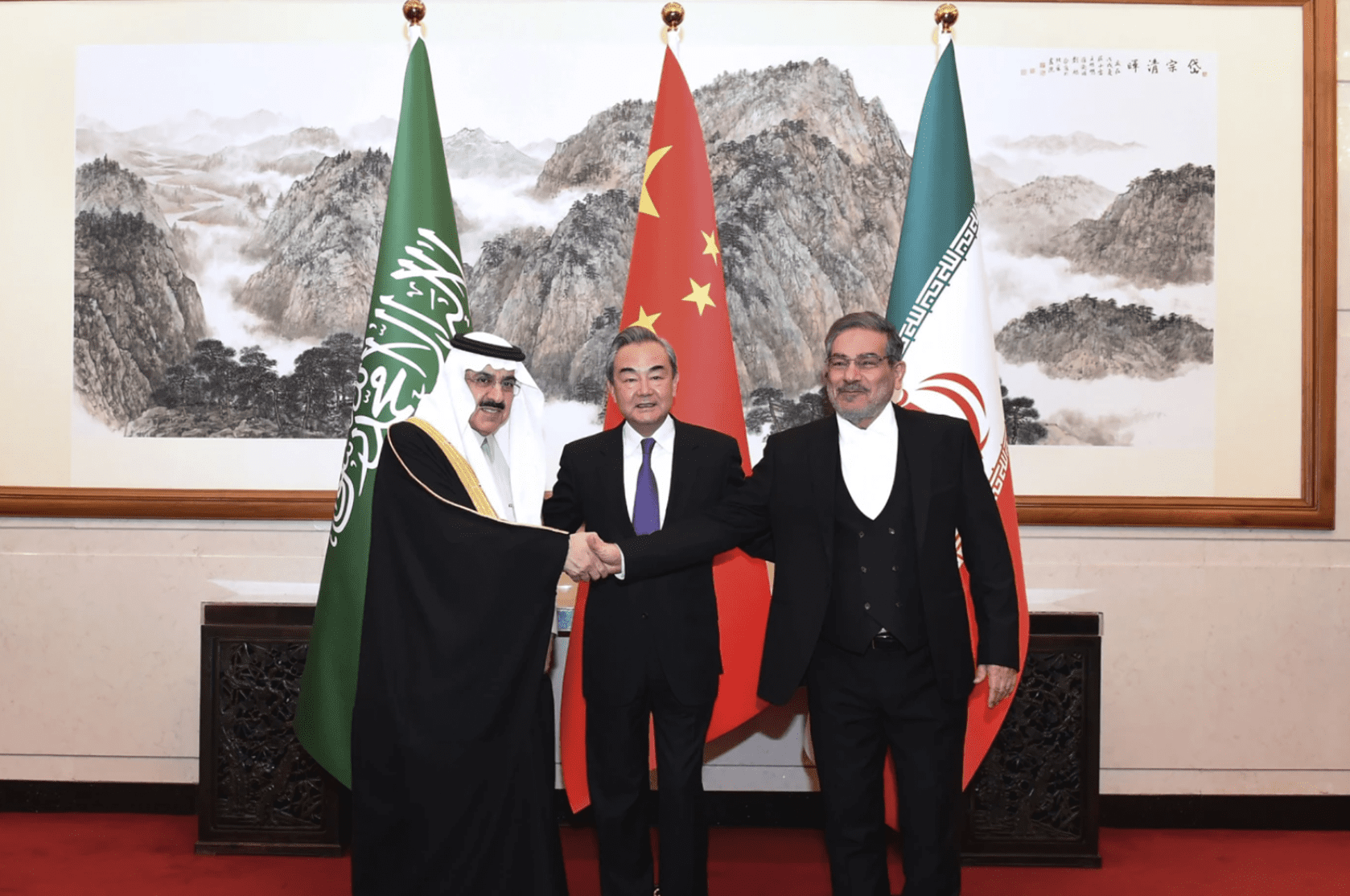

Pinning down a coherent way to describe Trump’s foreign policy evaded the Washington commentariat throughout his presidency. His administration cranked the dial on U.S. competition with China, assassinated an influential Iranian general, and brokered the Abraham Accords between Israel and a number of Arab states, while also alienating allies in Europe, signing a catastrophic deal with the Taliban, and withdrawing the United States from both the Iran nuclear deal and the Paris climate accords.

It was an approach forged by the president’s own whims and whichever faction of the bureaucracy around him had succeeded in getting his ear. “Donald Trump didn’t have an ideology or a philosophy either, because he couldn’t think coherently enough to have one,” Bolton says flatly.

Trump’s promises of ending the so-called forever wars tapped an anti-interventionist nerve running through both parties these days. But it is on the question of military aid to Ukraine that the isolationist streak in the Republican Party has been most pronounced. Eleven Republican senators voted against a $40 billion package for Ukraine last May, while Reps. Marjorie Taylor Greene, Chip Roy, and Matt Gaetz are among those who have called U.S. military aid for Ukraine into question, joining Fox News’ Tucker Carlson and Laura Ingraham. (Speaking at an event in Washington on Wednesday, former British Prime Minister Boris Johnson said he was “amazed and horrified by how many people are frightened of a guy called Tucker Carlson. … All of these wonderful Republicans seem somehow intimidated by his perspective.”)

Bolton is convinced that the isolationist sentiment that has welled up around Ukraine has more to do with fealty to Trump than the result of a strategic assessment of U.S. national security priorities. The former president’s personal distaste for Ukraine has been well documented by former White House officials. It emerged during impeachment hearings in 2019 that Trump had become convinced by what his former top Russia advisor Fiona Hill described as a “fictional narrative” that it was Ukraine, not Russia, that sought to interfere in the 2016 U.S. presidential election—and not in his favor.

“It colored his whole attitude toward Ukraine and therefore colored the minds of some people in Congress,” Bolton says.

U.S. intelligence officials concluded that the narrative was likely cooked up by Russian intelligence to undermine U.S. support for Kyiv. If Bolton’s theory is correct, that would mean that elements of the current resistance to sending further military aid to Ukraine may well represent, however unwittingly, the long tail of a Russian disinformation campaign still playing out in Washington.

There is an old saying in Washington that when it comes to choosing their presidential candidates, Democrats fall in love, while Republicans fall in line. In light of McCarthy’s humiliating road to become House speaker, I ask Bolton whether he still recognizes his party as it stands today. “Oh, sure. I still think the isolationist virus is a very small percentage of the party both in Congress and in the public at large,” he replies.

I tell him I’m inclined to agree, but the skeptic in me is unsure whether the quiet majority will win out against the vocal minority. But Bolton is ready for the fight.

“I don’t plan to rest on my laurels. Let’s have the debate. That’s how you find out who’s going to win and who’s going to lose. I’m ready for it.”