The world has truly turned upside down when a U.S. president begs America’s allies to have a United Nations agency go easy on a terrorist nuclear proliferator. The Biden administration’s reported pleading on behalf of Iran isn’t merely a tactical error about yet another biodegradable U.N. resolution. It’s a persistent strategic blindness that existentially threatens key U.S. partners and endangers our own peace and security.

Iran’s largely successful effort to conceal critical aspects of its nuclear-weapons complex from scrutiny by the International Atomic Energy Agency and Western intelligence services is nearing culmination. IAEA reports about Iran’s uranium-enrichment program—and Tehran’s disdain for IAEA inspections, extending over two decades—finally have the Europeans worried.

Instead of welcoming this awakening, President Biden is reportedly lobbying European allies to avoid a tough anti-Iran resolution at this week’s quarterly IAEA board of governors meeting. The administration denies it. But limpness on Iran’s nuclear threat fits the Obama-Biden pattern of missing the big picture, before and after Hamas’s Oct. 7 attack on Israel, including cash-for-hostages swaps with Iran as recently as last year.

Mr. Biden has two objectives. The first is to keep gasoline prices low and foreign distractions to a minimum before November’s election. The second is the Obama-Biden obsession with appeasing Iran’s ayatollahs, hoping they will become less medieval and more compliant if treated nicely. Both objectives are misguided, even dangerous.

Election worries about gas prices have also weakened U.S. sanctions against Russia, which are failing because of their contradictory goals. It simply isn’t possible to restrict Russian revenue while keeping U.S. pump prices low. The ayatollahs don’t worry about elections, but they know weakness when they see it, including Mr. Biden’s relaxed enforcement of sanctions on Iranian oil exports.

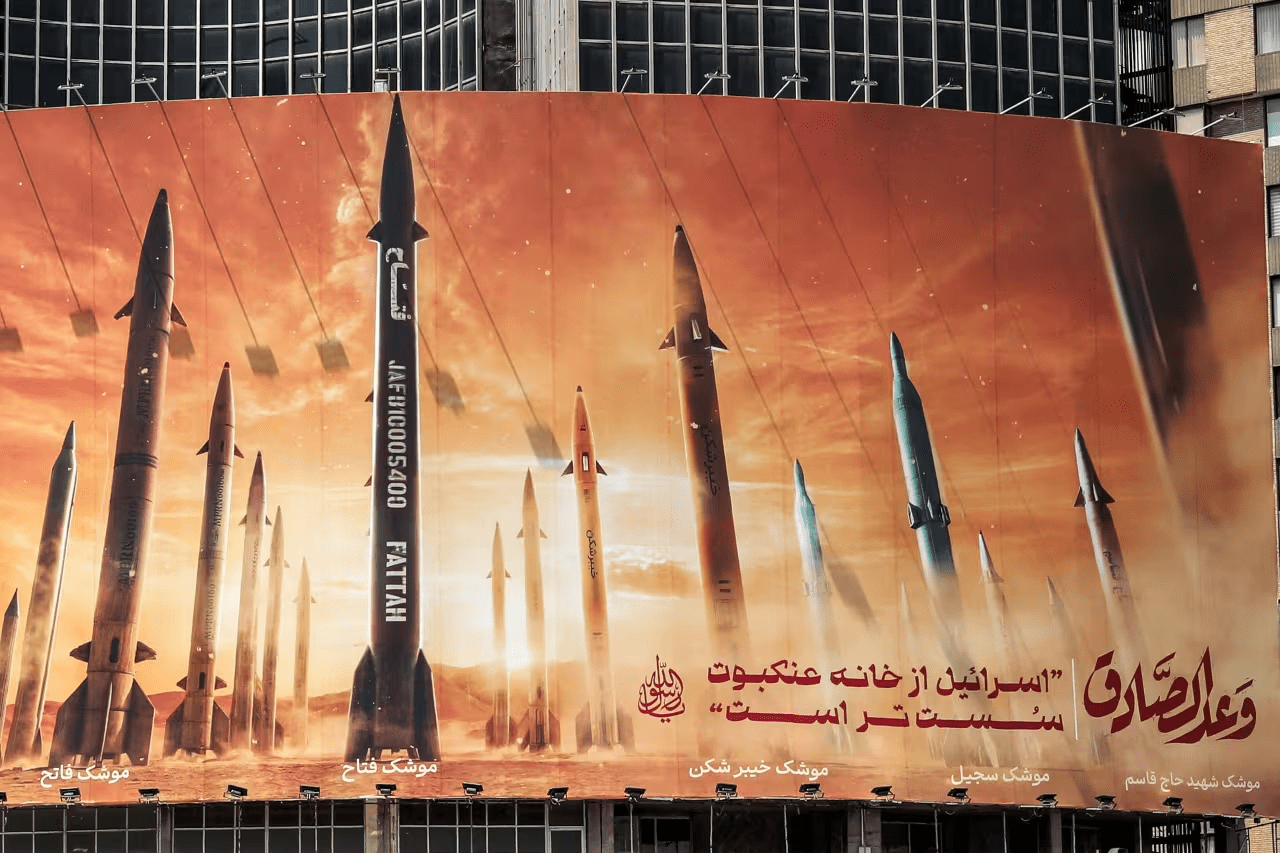

Mr. Biden’s greater mistake is refusing to acknowledge Iran’s “ring of fire” strategy to intimidate Israel and achieve regional hegemony over the oil-producing monarchies and other inconvenient Arab states. The foundational muscle for achieving these quasi-imperial aspirations is Iran’s nuclear program, precisely the issue at the IAEA. Starting in his 2020 campaign, Mr. Biden repeatedly alienated Gulf Arabs, especially Saudi Arabia, which felt particularly threatened by his zeal to rejoin the failed 2015 nuclear deal. Mr. Biden’s willingness to exclude Israel and the Arabs from negotiations with Tehran, as Mr. Obama did, convinced Arab governments that Washington was again hopelessly feckless. Israel concurred.

Arab leaders privately see the need to eliminate Tehran’s terrorist proxies. Saying so publicly, however—even quietly—requires political cover, which Washington has failed to provide. The Biden administration could have sought to destroy, not merely inhibit, the Iran-backed Houthis’ capacity to close shipping routes in the Suez Canal and Red Sea. Since the U.S. failed to do so, rising prices from higher shipping costs increase the risk of a de facto Iran-Houthi veto over freedom of the seas. Not surprisingly, Iran now threatens to blockade Israel itself.

Mr. Biden decided to concentrate world attention on Gaza rather than on Iran as the puppet-master. Doing so has helped obscure that Gaza is only one component of the larger ring-of-fire threat. Many Israelis, including several members of the war cabinet, have long focused on the close-to-home threat of Palestinian terrorists rather than the existential threat of a nuclear-armed Iran. This joint failure enabled Tehran’s propaganda to outmatch Jerusalem’s, leaving the false impression of a moral equivalence.

Had the U.S. and Israel explained the barbarity of Oct. 7 in such broader strategic terms, they would necessarily have concentrated attention on Iran’s coming succession crisis. Supreme Leader Ali Khamenei is old and ailing. President Ebrahim Raisi’s still-unexplained demise has already launched a succession struggle that could transform Iran. The U.S. and its allies should help the Iranian opposition fracture the Islamic Revolution at the top. Instead, Mr. Biden, who couldn’t conceive of overthrowing the ayatollahs, has dispatched envoys to beg Iran not to stir things up further before November.

Sending Tehran what diplomats call a “strong message” from the IAEA isn’t much, but treating Iran as if it calls the shots is far worse. Praying that Mr. Biden wakes up to reality may be the world’s only hope.

This article was first published in the Wall Street Journal on June 4, 2024. Click here to read the original article.