This article appeared in The Washington Post on December 10, 2020. Click here to view the original article.

By John Bolton

December 10, 2020

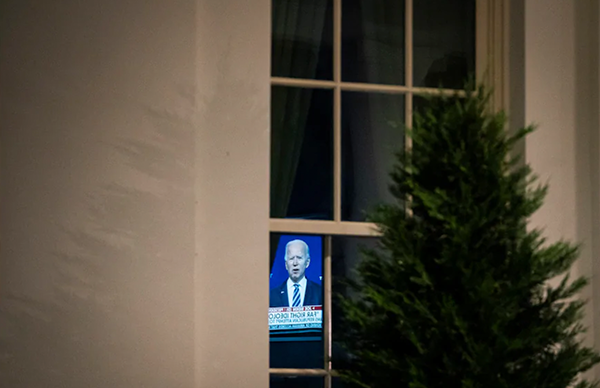

On Monday, Donald Trump will officially lose the 2020 presidential election. In their respective states, electoral college delegations chosen by the citizens will meet to cast their ballots. If there are no “faithless” electors, 306 votes will go to Joe Biden for president and Kamala D. Harris for vice president, and 232 to Trump and Mike Pence. There will be no lawful way to change this result.

Most Americans will be relieved that the election is over. Unfortunately, too many Republicans will see only the ratification of a “stolen election.” Why? Because for months Trump has proclaimed he could lose only through foul play, and because too few Republicans said this was nonsense.

Rather than “America First,” Trump’s true slogan is “Trump First,” so his fantasy will not end easily. Nonetheless, starting with the resolution of the electoral college vote, Republicans, and all Americans, can take significant steps to move beyond Nov. 3, without endless, debilitating reargument of what happened.

First, everyone — Republicans especially — should recognize that the national political dynamic will change irrevocably at noon on Jan. 20. It will never be the same again for Trump. There will be a new president, doing his job, whether Trump adjusts to it or not. Even though barely more than five weeks now remain until the transfer of power, many who have been unable or unwilling to feel the tectonic plates shifting will finally recognize the change. Mar-a-Lago is not the same as the Oval Office. Foreign leaders will not flock to Florida for meetings.

Despite four years as president, Trump never fully grasped the issues before him, and he won’t learn anything new once he leaves. His observations will become increasingly irrelevant.

Trump will not disappear entirely. But the thrill will assuredly fade.

Second, with this coming dramatic shift in the political universe in mind, every Republican as of next Monday’s electoral college vote should publicly acknowledge what they have known in silence for many weeks: Biden is the president-elect. We Republicans should all just say it and get it over with.

If confronted by bitter-enders, stuck on Trump and dreaming of continuing the fight, for example on Jan. 6 when the electoral college ballots are opened and counted in Congress, Republicans should take their cue from Nancy Reagan: Just say no.

Third, there is every reason to believe Republicans can make Democrats’ hold on the White House last just one term. Analysts across the political spectrum have noted the GOP’s November successes, other than Trump’s loss. Winning at all levels in coming elections, however, requires a party not obsessed with contemplating its 2020 presidential navel.

That will necessitate disbanding the GOP’s circular firing squads now blasting away in Georgia, Arizona and elsewhere. This internecine warfare is not along ideological lines; by any coherent measure, all the main participants are conservatives. The common denominator is that Trump set these dumpster fires to advance his own interests.

The Republican Party’s lasting strength is its focus on policy, not personalities, and certainly not cults. To reclaim the high ground, national, state and local party structures must focus impartially on enhancing support for all Republicans, not just Trump. We must have open debates on policy, and new platforms reflecting those debates. As long as Trump continues broaching a possible 2024 candidacy, this neutrality is threatened.

Any party official unable to remain impartial should be a candidate for retirement. Historically, after presidential-election defeats, Republicans have sought new party leadership. Following Barry Goldwater’s 1964 defeat, Ray Bliss took charge as national chairman, with excellent 1966 and 1968 results; after Gerald Ford’s 1976 loss, Bill Brock stepped up and laid the groundwork for Ronald Reagan’s 1980 victory.

This is an entirely normal intra-party transition. It is not about any particular losing candidate or party official, and saying so casts no blame. But without ironclad assurances of impartiality by current party officials, based on their personal honor, Republicans risk missing a big opportunity for revitalization. Contested elections for party positions are not bad things.

Fourth, speaking as a baby boomer, I make perhaps the most painful point: Republicans should begin thinking about finally selecting a non-boomer presidential candidate. Recalling Ronald Reagan’s line about Walter Mondale, the “youth and inexperience” of these late-comers may be a burden for them, but it should not be insuperable.

If Biden again bears the Democratic standard in 2024 — when he will turn 82 — and faces a non-boomer Republican opponent, the contrast will be palpable. If Biden doesn’t run, and a 78-year-old Trump is again the Republican nominee, the contrast will also be palpable. This one should not be hard for the GOP, as long as the succession is based on merit, not heredity.