This article appeared in The Wall Street Journal on February 15th, 2022. Click here to view the original article.

It’s been more than 75 years since the U.S. last faced an axis of strategic threats. Fortunately, that axis proved dysfunctional. Had it been otherwise, Japan and Germany would have systematically attacked the Soviet Union, not America, first.

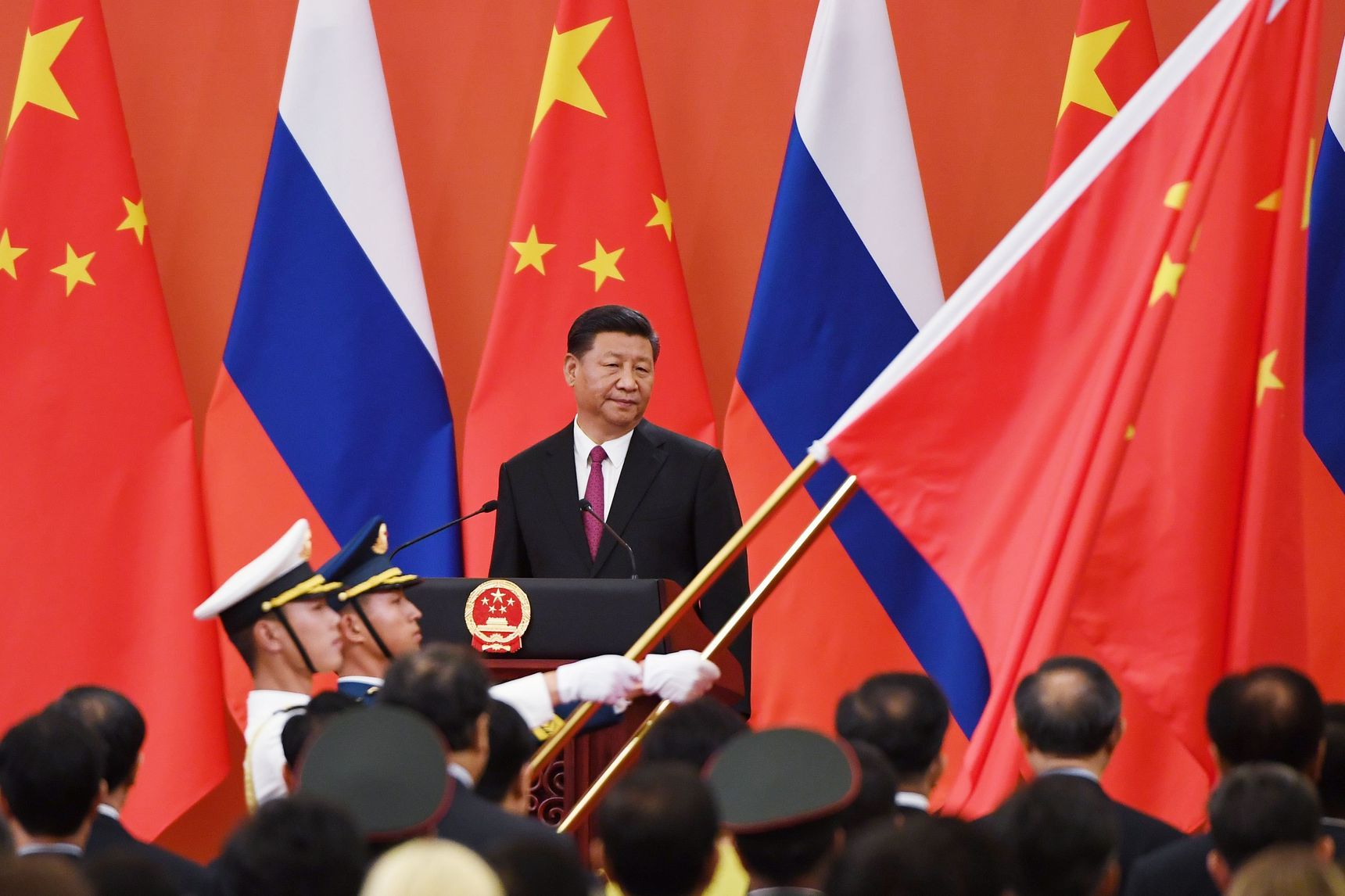

Our current strategic adversaries, Russia and China, aren’t an axis. They’ve formed an entente, tighter today than any time since de-Stalinization split the communist world. Involving some mutual interests and objectives, displays of support, and coordination, ententes are closer than mere bilateral friendships but discernibly looser than full alliances. The pre-World War I Triple Entente (Russia, France and Britain) is the modern era’s prototype.

Moscow is junior partner to Beijing, the reverse of Cold War days. The Soviet Union’s dissolution considerably weakened Russia, while China has had enormous economic growth since the death of Mao Zedong in 1976. Russia’s junior-partner status looks permanent, given disparities in population and economic strength (whatever today’s military balance), but Vladimir Putin seems determined to move closer to China.

This entente will last. Economic and political interests are mutually complementary for the foreseeable future. Russia is a significant source of hydrocarbons for energy-poor China and a longtime supplier of advanced weapons. Russia has hegemonic aspirations in the former Soviet territory, Eastern Europe and the Middle East. China has comparable aspirations in the Indo-Pacific region and the Middle East (and world-wide in due course). The entente is growing stronger, as China’s unambiguous support for Russia in Europe’s current crisis proves.

Washington would undoubtedly be more secure if it could sunder the Moscow-Beijing link, but our near-term prospects are limited. This entente, along with many other factors, renders especially shortsighted the common assertion that opposing China’s existential threat to the West requires reducing or even withdrawing U.S. support for allies elsewhere.

Barack Obama’s “pivot” or “rebalancing” to Asia produced a decade of variations on the theme that China matters and other threats don’t. Donald Trump agreed, although he wanted primarily to strike “the biggest trade deal in history” or impose tariffs if he couldn’t, along with assaulting China for the “Wuhan virus” when it became politically convenient. Some analysts argue that the global terrorist threat is diminishing and that hydrocarbon resources are becoming less important because of the green-fuel revolution. Both would mean that we could safely reduce U.S. attention to the Middle East. Thus, Joe Biden argued that withdrawing from Afghanistan was required to increase attention to China’s menace. Sen. Josh Hawley and others even believe we shouldn’t be deeply involved in the Eastern Europe crisis, to avoid diverting attention and resources from countering Beijing.

Such assertions about reduced or redirected U.S. global involvement are strategic errors. They reflect the misperception that our international attention and resources are zero-sum assets, so that whatever notice is paid to interests and threats other than China is wasted.

This is false, both its underlying zero-sum premise and in underestimating non-Chinese threats. Our problem is failing to devote anything like adequate attention or resources to protecting vital global interests. Political elites (who are noticeably lacking in figures like Truman and Reagan) focus on exotic social theories and domestic economics rather than national-security threats. America’s own shortsightedness, particularly an inadequate defense budget, makes us vulnerable to foreign peril. Washington must pivot not among competing world-wide priorities, but away from domestic navel-gazing.

Critically, those who exclusively fear China ignore the Russia-China entente. The entente serves to project China’s power through Russia, as Beijing also projects power through North Korean and Iranian nuclear programs. Moreover, Beijing closely assesses Washington’s reactions to crises like the one in Ukraine to decide how to structure future provocations.

Mr. Biden had it exactly backward in Afghanistan. The U.S. withdrawal not only signaled insularity and weakness, but allowed China and Russia to extend their influence in Kabul, Central Asia and the Middle East. Beijing and Moscow thereby also became more confident and assertive. And that’s not to mention that even the Biden administration admits that terrorism’s threat is rising again in Afghanistan.

Beijing is not a regional threat but a global one. Treating the rest of the world as a third-tier priority, a distraction, the U.S. plays directly into China’s hands. Pivoting to Asia wouldn’t strengthen America against China. It would have precisely the opposite effect and weaken our global posture.

We need to see this big picture before the Russia-China entente grows up to be an axis.

Mr. Bolton is author of “The Room Where It Happened: A White House Memoir.” He served as the president’s national security adviser, 2018-19, and ambassador to the United Nations, 2005-06.