The hostage deal has costs as well as benefits – and it’s the terrorists who stand to gain most

Beware of terrorists bearing gifts. Compassionate goals and unrelenting war make for a complex mix. While freeing Hamas’s October 7 victims is laudable, there are right and wrong ways to do so. There are costs as well as benefits. Here, Hamas has won a significant victory. Whether the deal sets a definitively negative precedent for Israel remains unclear, but it casts doubt on whether it will attain its legitimate goal of eliminating Hamas’s terrorist threat.

The agreement is fatally defective in many ways, even if it proceeded flawlessly (which it has not). Hamas is set to release 50 terror victims, and Israel will release 150 accused or convicted criminals, a ratio the reverse of what we should consider civilised. Equating innocent victims with law-breakers is morally appalling. One fifteen-year-old “child” Israel listed for possible release was convicted of attempted murder for stabbing a neighbor. Many are male teenagers. You can guess why. A critical argument for this deal now is removing hostages from danger, but it does nothing for those left behind.

The releases are occurring over four days, during which Israeli military activity is “pausing” operations. Undoubtedly, Israel will use the pause to prepare the next phase of hostilities, rotating and resupplying troops and the like. But Hamas terrorists are the real beneficiaries of a cessation of hostilities. They have been pounded by air, and hunted down inside and under Gaza in their extraordinary tunnel networks. Israel’s military campaign is just in its opening phases, but Hamas has been significantly damaged.

Why let up now? Hamas will use the pause to extricate its terrorists from a difficult position, exfiltrate assets and personnel into Egypt and Israel through undiscovered tunnels, and prepare southern Gaza for the next Israeli offensive. How many chances for faster advances or more surprise attacks will Israel lose due to this pause? How many more Israeli soldiers will die because of Hamas’s opportunity to set additional traps and further entrench itself?

If Hamas chooses to release more hostages, the pause will be extended one day for each ten hostages. What conceivable justification is there to allow your enemy to unilaterally determine the length of the pause? And what if “technical difficulties” mean only six hostages are released; does Hamas still get another day of respite? Israel will unfairly bear the onus of resuming hostilities, adding leverage to Hamas propaganda efforts to erase its own October 7 barbarity.

Inexplicably, both Jerusalem and Washington are suspending overhead surveillance of Gaza for six hours a day during the pause. This concession may be more significant than the pause itself because it denies Israel information about Hamas’s activities. Israel has agreed to be “eyeless in Gaza” during these terrorist-friendly time windows.

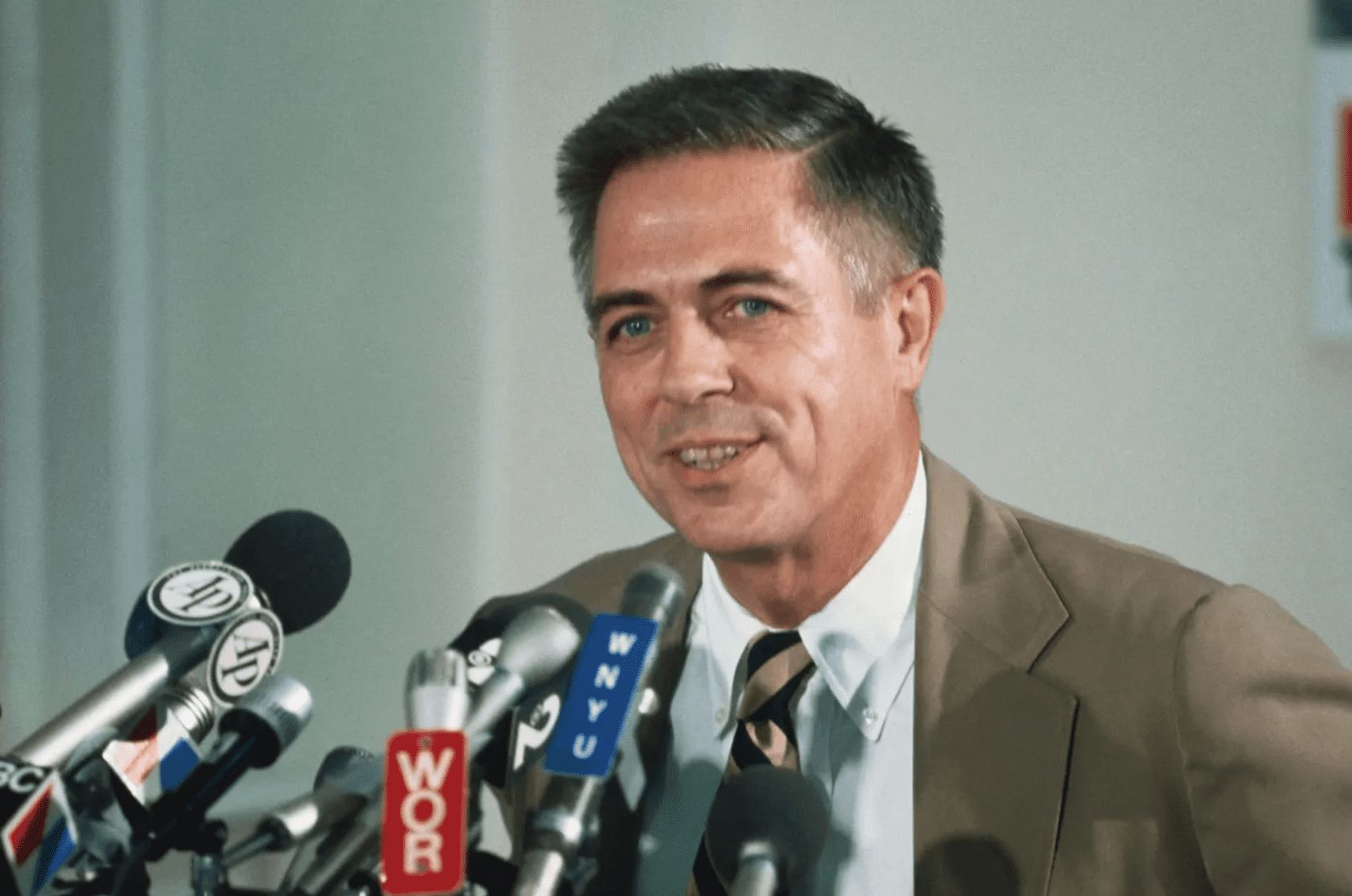

The White House boasts that the deal means “a massive surge of humanitarian relief” into Gaza, but without adequate assurances the relief will go to those in need. When Herbert Hoover launched America’s first major international relief effort in World War I, he insisted on two conditions: aid must go only to non-combatants, and the donors must distribute or closely monitor its distribution. We have no idea how much will fall into Hamas’s hands, enabling more terrorism.

Israel’s critical military problem is the opportunities it will miss by halting in mid-stream its increasingly successful assault. Hamas’s strategy is to take any pause, however short, and whatever its rationale, and stretch it into a permanent ceasefire. That may not happen on the first try, but the pressure on Israel to succumb will grow.

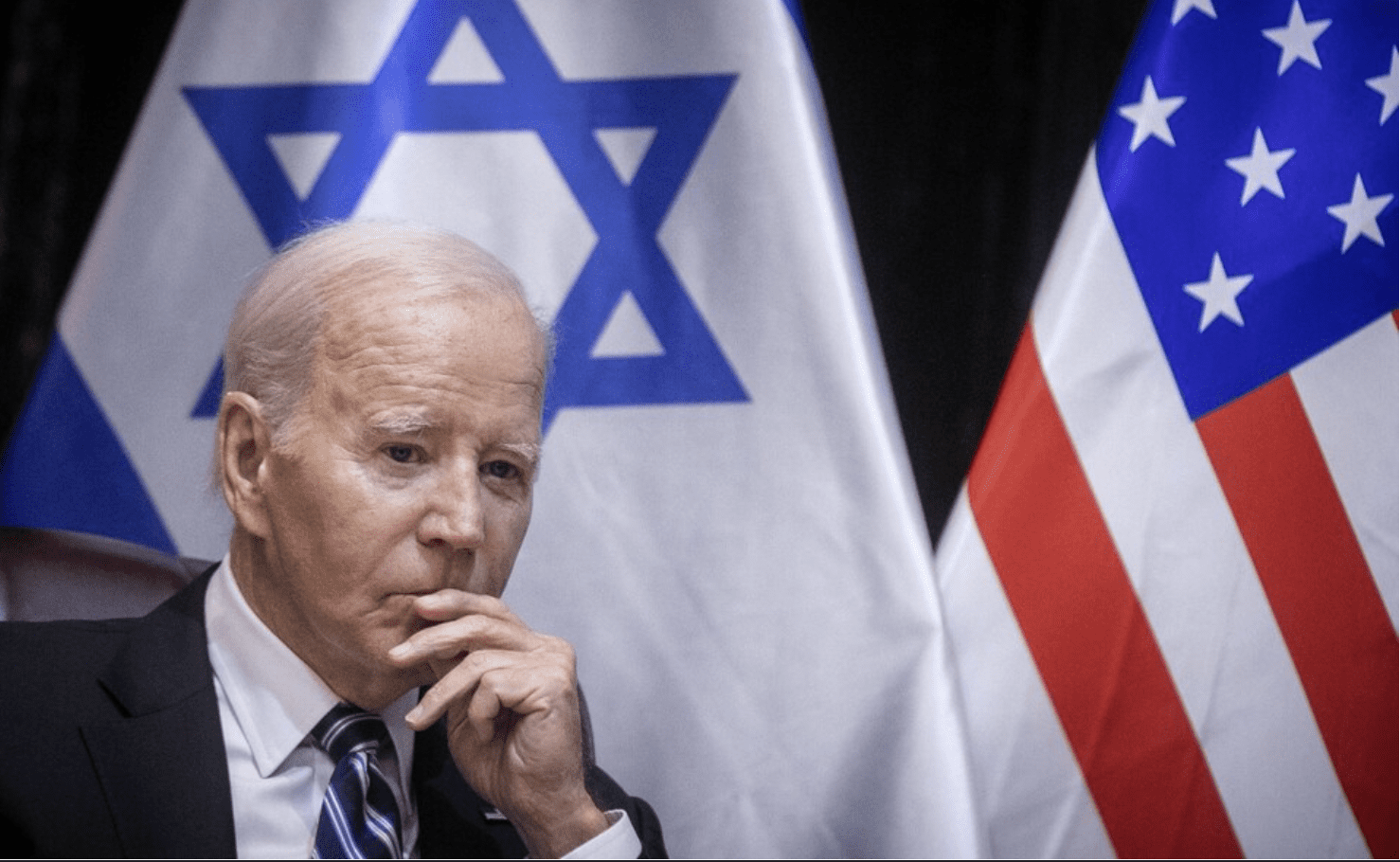

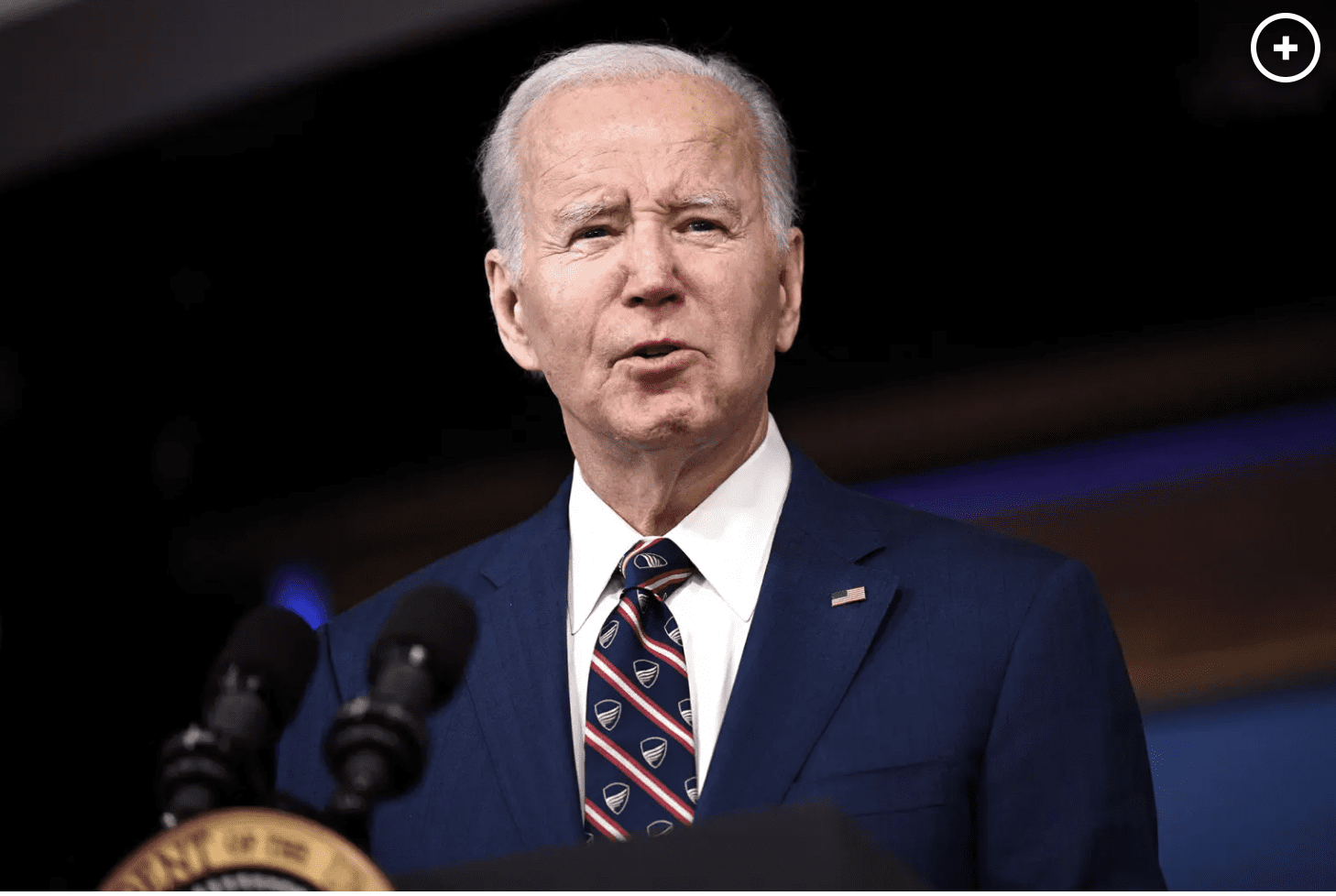

Israel’s critical political risk is seeing its determination to eliminate Hamas undermined. Even chancier is the strength of US backing, which is already weakening. Biden’s initially robust rhetorical support for Israel has cooled, and his resolve shrinks daily under the assault of the Democratic party’s pro-Palestinian Left-wing. His problems will grow more acute as the 2024 presidential campaign unfolds.

The benefits of freeing hostages are visible now. The much larger costs are on their way.

This article was first published in The Telegraph on November 24, 2023. Click here to read the original article.