No one lied us into invading, and what came later was its own set of decisions

This article was first published in National Review Plus Magazine on March 16, 2023. Click Here to read the original article.

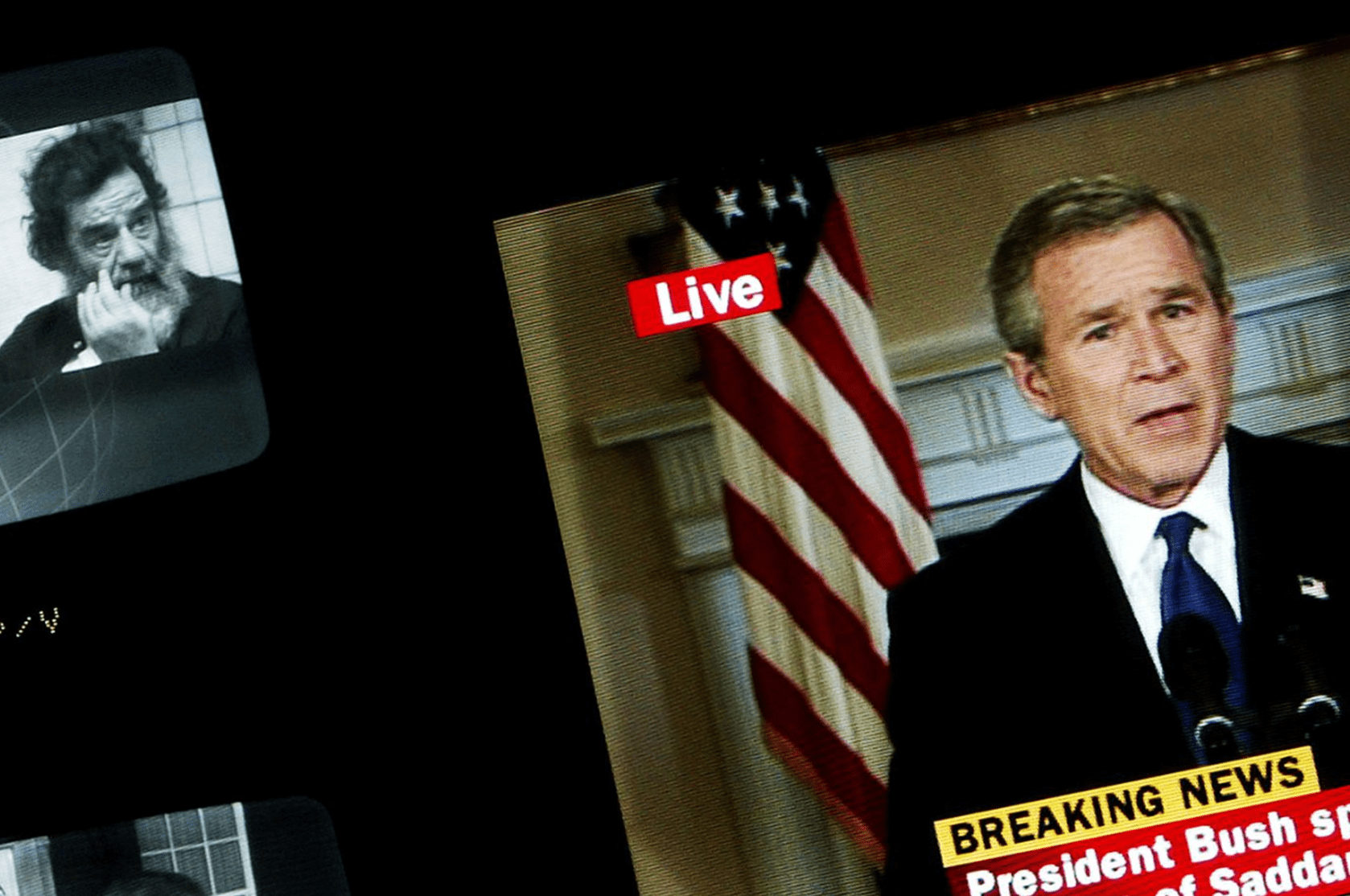

The 2003 invasion of Iraq and overthrow of Saddam Hussein were accomplished rapidly, with consummate skill and professionalism, and with thankfully low U.S. casualties. This period of major combat operations (March 20 until May 1) was close to flawless. Saddam’s day was over, and Iraq’s potential acquisition of weapons of mass destruction (WMD) was foreclosed, effectively in perpetuity. We achieved our goals.

These key facts are essentially indubitable. Instead, critics dispute whether deciding to invade, and American policy after toppling Saddam, were correct and justifiable. These are no small matters. But the critical point, typically ignored or misunderstood, is that the “Iraq War” is not one indivisible, 20-year-long block of granite that can be judged only all or nothing. Instead, the ongoing U.S. presence there embodies a long, complex history, some of which Washington got right and some it didn’t.

The reasons to invade were clear and compelling: Saddam directly threatened U.S. security by pursuing WMD and supporting terrorism. After the 1991 Gulf War, U.N. inspectors found Iraq’s nuclear-weapons program far more advanced than indicated by previous intelligence assessments. Despite the physical destruction of centrifuges and other assets by the U.N. and the International Atomic Energy Agency in the mid 1990s, Saddam retained the program’s core intellectual base: over 3,000 nuclear scientists and technicians, his “nuclear mujahideen,” to re-create it later. Under Security Council Resolution 687, Saddam also declared large supplies of chemical weapons and related assets. Pressed repeatedly by the U.N., Iraq claimed to have destroyed its chemical-weapons program but obstructed U.N. inspectors, refusing to supply any proof of its claims, leading essentially all observers to believe that it retained large chemical-weapons capabilities. Biological weapons, the easiest of the WMD to conceal or destroy, were suspected but not proven. Iraq’s ballistic-missile programs had continued.

All this WMD activity was undertaken against the day when U.N. economic sanctions were lifted and weapons inspectors departed. Indeed, sanctions were already collapsing when President George W. Bush was inaugurated. Proposals to “fix” the problem, such as “smart” (more-targeted) sanctions, were at best fig leaves, acknowledging the U.N.’s disarray (both politically and operationally) and its essentially inevitable failure. There are only two kinds of sanctions, but they are not “smart” versus “dumb.” The real dichotomy is between crushing sanctions, swiftly and massively imposed and then rigorously enforced, and all others. Most sanctions historically fail and become mere virtue-signaling. The lesson of twelve years of failed Iraq sanctions between 1991 and 2003 is that sanctions can help avoid war only if they are enforced cold-bloodedly. The U.N.’s Iraq efforts, especially the oil-for-food program, failed in every material respect.

No one lied about WMD. In the wake of 9/11 and the still-unresolved anthrax attacks, Saddam’s murderous history, domestically and abroad, made it entirely prudent to ensure that he could never again threaten America, the region, or the world with weapons of mass destruction. Melvyn Leffler’s recent book, Confronting Saddam Hussein, while not flawless, should be compulsory reading on President Bush’s pre-war decision-making. Post-war findings about the actual state of Iraq’s WMD do not invalidate the pre-war reasoning. Saddam’s real threat was not merely his intentions and capabilities in 2003 but what they could be in the future if he retained power. This was well understood and endorsed across America, which is why congressional and public support for the invasion was overwhelming. Indeed, in hindsight, Saddam should have been removed in 1991 after his unprovoked aggression against Kuwait.

In fact, the brunt of contemporary criticism focuses not on pre-war decision-making but on U.S. policies and what came after May 1, 2003. Certainly, the rapid, near-total collapse of Iraq’s government and the resulting disorder are facts. The real issue, however, is whether Washington should have moved immediately to turn governance functions over to Iraqis, or created, as it did, the Coalition Provisional Authority, which kept America intimately involved in Iraqi politics far longer than initially expected. Important decisions such as de-Baathification, the dissolution of Iraq’s army, and the broader efforts at nation-building and democracy promotion are also all debatable, especially with 20/20 hindsight. Nonetheless, despite the innumerable difficulties encountered and missteps U.S. authorities made, by embracing the 2007–08 “surge,” President Bush in fact reduced internal insurgency to a manageable, marginal level.

The key point, however, is not that these or other individual decisions were right or wrong but instead that they did not inevitably, inexorably, deterministically, and unalterably flow from the decision to invade and overthrow, and the rationale for it. Whatever Bush’s batting average in post-Saddam decisions (not perfect, but respectable, in my view), it is separable, conceptually and functionally, from the invasion decision. The subsequent history, for good or ill, cannot detract from the logic, fundamental necessity, and success of overthrowing Saddam, a threat to American national security since he invaded Kuwait in 1990.

The biggest “Iraq War” mistake was Barack Obama’s catastrophic 2011 military withdrawal, which even Obama recognized as an error, reinserting U.S. forces in 2014 to counter the rise of ISIS. Withdrawing, obviously, was precisely the opposite of Bush’s decision to attack, which makes it hard to see these polar opposites as parts of the same block of granite to be judged as a unity. Moreover, other unforeseen post-2003 events had significant negative impacts on the Middle East, such as the Arab Spring’s rise and especially its collapse, and the resurgence of radical Islamism. How can a 2003 decision be faulted because of subsequent events that completely surprised the world?

Equally wrong was the Bush administration’s failure to take advantage of its substantial presence in Iraq and Afghanistan to seek regime change in between, in Iran, before Tehran’s own WMD programs neared success. Those who say invading Iraq distracted from Afghanistan, or that attacking Iraq rather than Iran prioritized the wrong target, should still agree that we had a clear opportunity to empower Iran’s opposition to depose the ayatollahs. Unfortunately, however, as was the case after expelling Saddam from Kuwait in 1991, the United States stopped too soon.

In any case, Iran policy, like so much else, was not predetermined by the 2003 invasion decision. Lumping everything together as “Iraq War” critics do disserves careful analysis of what America accomplished, or didn’t.