By John R. Bolton

Posted on National Review Online

The Vienna deal sets up a choice of bad and worse.

When Congress returns to Washington in September, it faces one of its most critical decisions in recent years: whether to reject the Vienna nuclear deal and ostensibly stop President Obama from waiving economic sanctions against Iran. Unfortunately, many staunch opponents of the deal, who rightly criticize its debilitating errors, inadequacies, and omissions, nonetheless misapprehend America’s alternatives once Congress acts. They contend that, after blocking Obama’s waiver authority, we should not only maintain the current nonproliferation sanctions but impose stricter ones, both U.S. and even international. Under this theory, Iran would sooner or later be forced to seek new negotiations, in which Washington could extract a better agreement. And in the absence of such an agreement, they argue, “no deal is better than a bad deal.”

This is all fantasy. We have been overtaken by events, no matter how Congress votes.

Obama’s mistakes, concessions, and general detachment from Middle Eastern reality for six and a half years make it impossible to travel in time back to a theoretical world where sanctions might have derailed Iran’s nuclear-weapons program.

If Obama can save the Vienna agreement from Congress, he will lift sanctions for the remainder of his presidency. Alternatively, if his veto is overridden and U.S. sanctions remain in place, Europe, Russia, China, and everyone else will nonetheless proceed to implement the deal on their own. (And given Obama’s propensity not to enforce laws with which he disagrees, which he is already signaling in this case, U.S. sanctions will almost certainly prove ineffective.) Either way, it is naïve to think that a new Republican president in January 2017 will find any takers internationally to revive sanctions.

However Congress votes, Iran will still be marching inexorably toward deliverable nuclear weapons. Deals don’t constrain the mullahs, who see this capability as critical to the 1979 Islamic Revolution’s very survival. Not surprisingly, therefore, existing sanctions have slowed down neither Iran’s nuclear-weapons program nor its support for international terrorism. General James Clapper, Obama’s director of national intelligence, testified in 2013 that sanctions had not changed the ayatollahs’ nuclear efforts, and this assessment stands unmodified today. Tehran’s support for such terrorists as Hezbollah, Hamas, Yemen’s Houthis, and Syria’s Assad regime has, if anything, increased. As for the sanctions’ economic impact on Iran, Clapper testified that “the Supreme Leader’s standard is a level of privation that Iran suffered during the Iran–Iraq war,” a level that Iran was nowhere near in 2013 and is nowhere near today.

In short, to have stopped Tehran’s decades-long quest for nuclear weapons, global sanctions needed to match the paradigm for successful coercive economic measures. They had to be sweeping and comprehensive, swiftly applied and scrupulously adhered to by every major economic actor, and rigorously enforced by military power. The existing Security Council sanctions do not even approach these criteria.

First, the scope of the Iran sanctions’ prohibitions has always been limited, and they have been imposed episodically over an extended period of time, thereby affording Tehran ample opportunity to minimize their impact through smuggling, cheating, and evasion. And while the sanctions’ breadth gradually expanded, the Council’s typical approach was to prohibit trade only in certain items or technologies, or to name specific Iranian businesses, government agencies, or individuals with which U.N. member states were forbidden to do business. This very specificity made sanctions far easier to evade. If, for example, the ABC firm was named to the sanctions list, it took little effort to create a cutout company called XYZ to engage in precisely the same proscribed activities.

Second, key foreign countries are decidedly uneven in adhering to sanctions. Russian and Chinese compliance is notoriously lax, and other countries are worse. Under Iran’s sway, Iraq has been openly and notoriously facilitating Tehran’s oil exports by providing false documentation of Iraqi origin or purchasing Iranian oil for Iraqi domestic consumption, thereby freeing Baghdad’s oil for export. The Obama administration itself repeatedly granted waivers to countries that claimed they needed to import Iranian oil. Although clandestine sanctions violators do not publish audited financial statements, creative criminal minds (and not a few creative entrepreneurial minds) have found enough slack in the sanctions to keep Iran afloat, even if its citizens suffered economically. No one has ever described the ayatollahs as consumer-society-friendly.

Finally, it was largely national law-enforcement agencies, rather than military forces, that monitored the sanctions. Unsurprisingly, the quality of such efforts varied greatly, and the Security Council hardly matches the Pentagon in command-and-control authority.

In recent history, the only sanctions regime to approximate the ideal paradigm was that imposed on Saddam Hussein in 1990, just days after Iraq invaded Kuwait. Security Council Resolution 661 provided that all states “shall prevent . . . the import into their territories of all commodities and products originating in Iraq or Kuwait” except food, medicine, and humanitarian supplies. That is the very definition of “comprehensive,” and the polar opposite of the congeries of sanctions imposed on Iran.

Significantly, while Resolution 661 approached the theoretical ideal, even its sanctions failed to break Saddam’s stranglehold on Kuwait. Had Washington waited much longer than it did before militarily ousting Saddam, Kuwait would have been thoroughly looted and despoiled.

Thus, even strict, comprehensive, rigorously enforced sanctions are not necessarily enough to stop a determined adversary. Other critically important conditions, such as a truly credible threat of military force, must accompany sanctions. In 1990–91, the United States and a multinational coalition presented just such a credible threat, but Saddam nonetheless refused to back down, resulting in his humiliating military defeat. In 2002–03, Saddam yet again faced a credible military threat and again refused to back down. He thereupon not only lost militarily but also lost his regime and ultimately his life. Does anyone truly believe that Barack Obama’s fainthearted utterances that “all options are on the table” carry a credible threat to the mullahs, or that their hearing is any better than Saddam’s?

Finally, there must be a U.S. negotiator who knows how to negotiate. In 1990–91, Secretary of State James Baker made every effort to find a diplomatic solution meeting U.S. criteria, including a last-minute Geneva meeting with Iraqi foreign minister Tariq Aziz. Baker was prepared to try diplomacy but not prepared to concede the key point: immediate Iraqi withdrawal from Kuwait. His successors under Obama didn’t have that steel, and the results show.

We do not face the hypothetical question whether, five, ten, or twenty years ago, a better deal with Iran might have been possible. Even if we could honestly answer that question affirmatively, the option no longer exists. As we look forward, hard as it may be to swallow, there is no other deal available. Obama is right when he makes this point, although for all the wrong reasons.

Iran aside (since Tehran is obviously delighted with the deal), none of the other parties to the Vienna agreement have any interest in even considering resurrecting a stricter sanctions regime. Russia and China, as just noted, have hardly adhered to Security Council sanctions these last eight-plus years, and they are eagerly preparing to eliminate even the pretense of compliance.

In April, before the agreement was signed, Vladimir Putin issued a decree authorizing the long-stalled sale of the S-300 anti-aircraft system to Iran. Even though S-300s were not actually barred by U.N. sanctions, Putin’s decree signals the start of an Oklahoma land rush of business for Russia, from nuclear reactors (for “peaceful” uses, of course) to military equipment and more. In July, Iran’s Quds Force commander, Qassem Suleimani, visited Moscow in open disdain of theoretically still-operative sanctions to discuss sales of weapons, including the S-300. Given all the evidence, there is simply no basis to conclude that an economically troubled Moscow wants to close its bazaar to Iran.

China is already poised to make multibillion-dollar capital investments in Iran’s oil-production and refining capacities, thereby giving it privileged access to Iran’s oil and natural gas in the future while also boosting Beijing’s competitive edge in extracting deals from other producers. Moreover, China and Russia both long to build a parallel global economic structure to challenge the one now dominated by Western institutions. From dethroning the U.S. dollar as the world’s reserve currency, to creating an interbank funds-transfer system to compete with the SWIFT wire-transfer system in global markets, to sidelining the International Monetary Fund and the World Bank through such institutions as the new Asian Infrastructure Investment Bank, Beijing and Moscow are looking for openings. Lifting the Iran sanctions gives them a new opportunity to exploit while also affording the Kremlin indirect relief from sanctions in response to its military intervention in Ukraine, by providing alternative business opportunities now denied. What possible incentive would Russia and China have to put Iran, a potentially major player in their alternative economic universe, back under pressure?

European firms are already locking up massive trade and investment deals with Tehran and pressuring their governments for even more. Germany, for example, saw sanctions reduce its annual trade with Iran from $8 billion to $2 billion; in slow economic times, the prospect of returning to or exceeding pre-sanctions revenue levels is compelling. And once the economic benefits begin to flow, Europeans will fiercely resist reinstituting sanctions. (This fundamental commercial reality is yet another reason the Vienna agreement’s “snapback sanctions” could never work.) It is little wonder that Germany’s ambassador to Washington, Philipp Ackermann, recently said, “It would be a nightmare for every European country if this is rejected.”

There was a recent flurry surrounding reports that Jacques Audibert, foreign-policy adviser to French president François Hollande, had said that Iran would eventually return to the negotiating table if Congress rejected the Vienna deal. The French immediately went into full denial mode, but the most telling evidence was Foreign Minister Laurent Fabius’s making an on-his-knees pilgrimage to Tehran. Atoning for his earlier public disagreements with Obama’s disastrous concessions during the negotiations, Fabius extolled the prospects for business and invited Iran’s President Rouhani to Paris this November. Mercantilism is alive and well in Paris: When it comes to advancing French international commercial interests, even Socialist governments know the drill.

More happy news came on August 12, when Switzerland announced that it was lifting its sanctions immediately. Not a U.N. member — and hence not bound by Security Council decisions anyway — the Swiss government stressed its “interest in deepening bilateral relations with Iran.” Given the reach of Swiss financial and mercantile connections, this is a black hole for any effort to maintain sanctions against Tehran.

Nor are U.S. businesses blind. Ned Lamont, Connecticut’s 2006 Democratic Senate nominee, traveled to Tehran in June with — of all things — a delegation from the Young Presidents’ Organization. He reported that “Turk, German, and Chinese businesspeople were congesting the elevators and filling the conference rooms” of his hotel seeking deals. It was, said Lamont, “a modern-day bazaar, with businesspeople from around the world busily negotiating ventures.” Lamont’s joyful conclusion was that the “train had left the station and it is too late for the mullahs or the U.S. Senate to derail it.”

These accelerating developments demonstrate why relying on economic sanctions to coerce Iran was a chancy strategy from the start. Neither our allies nor Obama’s Washington are supple enough to exercise the economic power that sanctions imply, turning the heat up and down in carefully calibrated degrees to achieve the pleasure or pain desired. Once gone, sanctions are gone forever. The Vienna agreement itself proves that sanctions are a fairly blunt instrument. If the deal’s “snapback sanctions” are ever invoked for Iranian violations (as noted above, a dubious proposition), Tehran is then released from its obligations. What kind of penalty is it that frees the country being penalized from its other commitments?

As floods of newsprint have explained, the agreement will not stop Iran from getting nuclear weapons, whether Iran complies with its terms or, more likely, is already violating them. Obama’s deal is a born failure for reasons we need not elaborate further here. And when he says that the alternative to his failed deal is “some kind of war” (a phrase that obscures more than it reveals), he is simply continuing his efforts to sell a bad deal.

Understanding the reality that, in today’s circumstances, the mullahs never intended to agree to — or follow — any deal that could satisfy America clarifies why our alternatives as we look forward are decidedly limited no matter how Congress votes: Either Iran remains solidly on a path to deliverable nuclear weapons, sooner rather than later, or someone uses military force to prevent that outcome. In fact, that has been the reality for the past decade, despite Herculean efforts by many to avoid facing it.

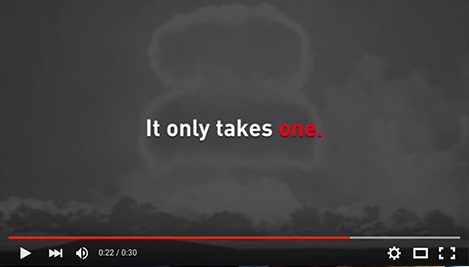

Accordingly, as of today, only a preemptive military strike can block Iran from becoming a nuclear-weapons state. We can understand why politicians flee from publicly considering the military option, just as we can understand why Obama tries to shoehorn debate into a “my way or war” dichotomy. But neither wishful thinking nor outright deception can change the fundamental strategic reality. That facing reality is unpalatable politically does not mean we can imagine another reality into existence. The spinmeisters can contemplate how to “message” the point, but America must recognize the facts it faces once Congress votes.

To stop Iran from achieving its 35-year goal of deliverable nuclear weapons, either America or Israel must be prepared to use military force. Obviously, under Obama, Washington has essentially left the field. Although he has said repeatedly that he wants to prevent Iran from obtaining nuclear weapons, not contain it after the fact, containment is Obama’s only remaining option. This explains why Secretary of Defense Ashton Carter is offering advanced weapons and increased cooperation to the Arab oil-producing monarchies. These are the classic foundations of a containment strategy.

The Gulf Arabs will undoubtedly accept Carter’s offers, and much more if they can get it. Deep down, however, they have no faith that, if they find themselves threatened by Iran, they are genuinely protected by America’s conventional or nuclear umbrella. Why should they? Ask Israel how it feels. Not surprisingly, therefore, a regional nuclear-arms race is already under way, led by Saudi Arabia, Egypt, and Turkey. This is one more compelling reason to stop Iran now. Taken alone, the Vienna deal already inflicts a mortal wound on the Nuclear Non-Proliferation Treaty, but a fully nuclearized Middle East would be a global strategic catastrophe.

Deep down, the Gulf Arab states have no faith that, if they find themselves threatened by Iran, they are genuinely protected by America’s conventional or nuclear umbrella. Why should they?

Accordingly, the spotlight falls on Israel, which twice before has struck nuclear-weapons programs in hostile states (Iraq in 1981 and Syria in 2007). Israel’s current options are hardly new or different. Jerusalem must choose between a world after a military strike and a world with a nuclear enemy whose objective is Israel’s destruction. It does not have the choice of preserving the world as it is today, because that world is rapidly becoming a world with a nuclear Iran (as before with Iraq or Syria).

Neither alternative is palatable, but in similar circumstances, Israel has not hesitated. In neither case, perhaps incomprehensibly to some, did the Middle East promptly descend into war and chaos. No other regional power wanted Saddam to have nuclear weapons (neither in 1981 nor thereafter), and, despite the flurry of anti-Israel activity at the United Nations, there were no sustained consequences following Israel’s attack. After Israel’s 2007 strike on Syria, Arab reaction was almost entirely muted, because the Arabs suspected that the al-Kibar reactor was a joint venture between Damascus and Tehran. The Sunni Arabs didn’t want a nuclear Iran in 2007, and they don’t want it now. Not only will the Arab monarchies quietly accept a preemptive Israeli military strike against Iran, some might even cooperate. This is how national interests actually work in international affairs.

Obviously, such a dangerous and complicated mission raises a host of questions. Can Israel succeed alone? Not as well as the United States could, to be sure, but well enough. As the British statesman Mick Jagger once wrote, “You can’t always get what you want, but if you try sometimes, you just might find you get what you need.” Israel has the military capability to cause massive damage to key choke points in Iran’s nuclear program (at least, those we know about), notably the Isfahan uranium-conversion plant, the Natanz uranium-enrichment facility, and the Arak reactor and heavy-water-production facility.

Isfahan and Arak are above ground and constitute fairly easy targets. Indeed, little-known Isfahan is both particularly important and particularly vulnerable. If Iran cannot convert uranium from the solid U3O8 to the gas UF6, its centrifuges cannot operate. Natanz is buried and hardened and will pose more obstacles for Israel than for America, but Israel can do the necessary. The Fordow uranium-enrichment facility is a more serious problem for Israel, but there is little doubt Jerusalem can close the entrance tunnels, air shafts, and electrical connections going deep underground. Preventive maintenance, in the form of small-scale Israeli strikes, to keep them closed may be needed over the years, but it’s hard for scientists to work when they can’t breathe.

Iran, of course, would respond. Herein lies the greatest danger and the hardest decision for Prime Minister Netanyahu’s government. Iran would most likely retaliate by unleashing Hezbollah and Hamas to rocket Israeli targets, especially terrorizing civilian areas. What is not so likely is that Iran would take any action that would generate a U.S. military response, such as closing the Strait of Hormuz, mining the Persian Gulf, or attacking the Gulf Arab states or deployed U.S. forces in the region. Losing their nuclear program would be bad enough for the ayatollahs. Losing their navy, air force, and who knows what else at American hands, even under Barack Obama, would be far worse, and potentially fatal to the regime itself.

Other speculation about Tehran’s response is fanciful. Some say an attack would cause Iran to accelerate its nuclear efforts. Compared with what? And it’s hard to accelerate when key elements of your program have been reduced to ashes. Others say Iran would increase its terrorist activity worldwide — but could it do much more than it can when its assets abroad are unfrozen under Vienna and it receives billions of dollars in economic windfalls? We should not be blind to any possibility, of course, but we must remain focused and objective.

For America, an Israeli attack also has potentially enormous consequences, including the economic risks and the threat to our forces in the Gulf. But every potential increase in risk to the United States and to each of our allies consequent upon an Israeli preemptive strike will, whether our allies realize it or not, be far higher, and permanent, when Iran acquires deliverable nuclear weapons. As with Israel, our real self-interest lies in facing the threat now before it metastasizes and becomes truly nuclear.

If Jerusalem strikes Iran, we will undoubtedly learn of it only after operations have commenced. Given the level of distrust between Israel and Obama, there is essentially no chance we will receive advance notice. Nonetheless, America should be immediately prepared to do two things to help Israel. First, politically and diplomatically, we should argue unhesitatingly that a preemptive Israeli strike is a legitimate exercise of Israel’s inherent right of self-defense. In an age of weapons of mass destruction and insignificant attack-warning times, this is basic common sense for us.

Second, Congress should immediately authorize and appropriate all necessary assistance for Israel to allow it to defend itself against Hamas and Hezbollah or direct Iranian retaliation. Israel’s military would probably expend significant resources and suffer heavy losses of men and matériel over Iran. To defend its civilians adequately, Israel could brook no delay in suppressing hostile activity from Lebanon’s Bekaa Valley or the Gaza Strip. Obama might procrastinate and equivocate, but Congress must do everything it can to force his hand.

These are bitter, unpleasant choices. They have been for 15 years or more. They are nonetheless still preferable to a nuclear Iran. Welcome to Obama’s post-Vienna world.