To download this plan as a PDF, please click here now.

I Background:

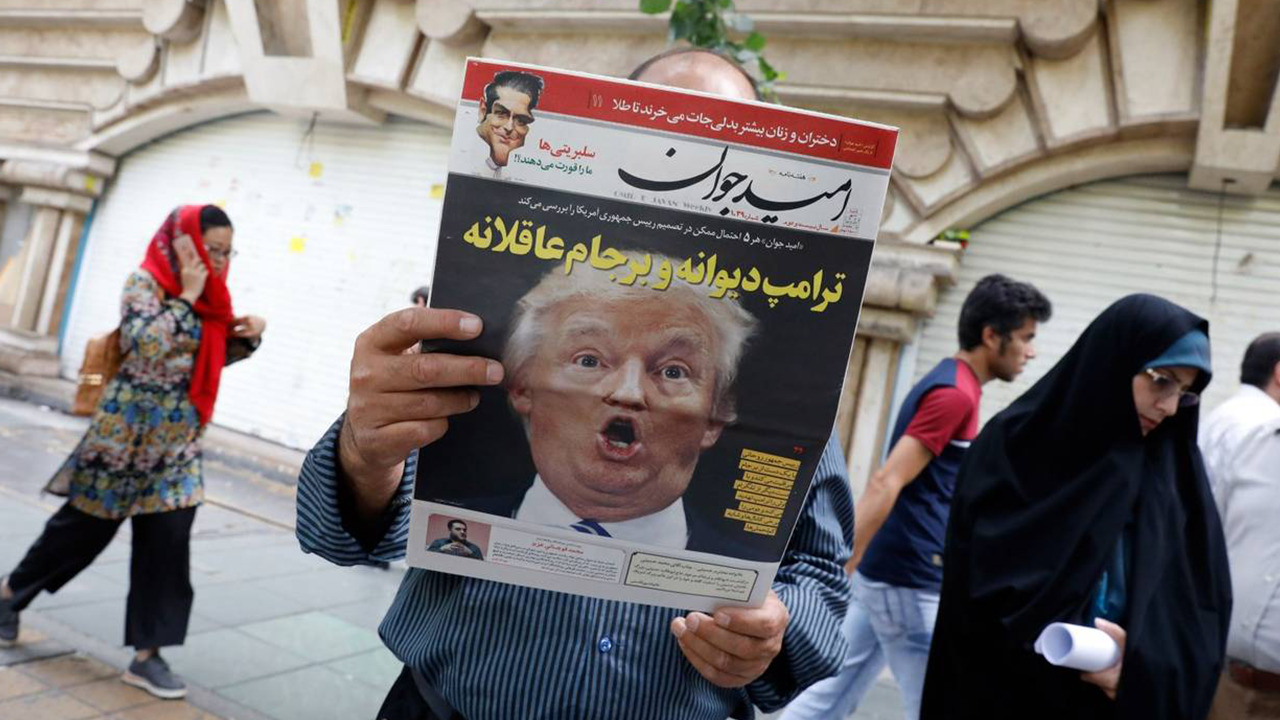

The Trump Administration is required to certify to Congress every 90 days that Iran is complying with the July 2015 nuclear deal (the Joint Comprehensive Plan of Action – JCPOA), and that this agreement is in the national security interest of the United States.1 While a comprehensive Iranian policy review is currently underway, America’s Iran policy should not be frozen. The JCPOA is a threat to U.S. national security interests, growing more serious by the day. If the President decides to abrogate the JCPOA, a comprehensive plan must be developed and executed to build domestic and international support for the new policy.

Under the Iran Nuclear Agreement Review Act of 2015, the President must certify every 90 days:

(i) Iran is transparently, verifiably, and fully implementing the agreement, including all related technical or additional agreements;

(ii) Iran has not committed a material breach with respect to the agreement or, if Iran has committed a material breach, Iran has cured the material breach;

(iii) Iran has not taken any action, including covert activities, that could significantly advance its nuclear weapons program; and

(iv) Suspension of sanctions related to Iran pursuant to the agreement is—

(I) appropriate and proportionate to the specific and verifiable measures taken by Iran with respect to terminating its illicit nuclear program; and

(II) vital to the national security interests of the United States.

U.S. leadership here is critical, especially through a diplomatic and public education effort to explain a decision not to certify and to abrogate the JCPOA. Like any global campaign, it must be persuasive, thorough and accurate. Opponents, particularly those who participated in drafting and implementing the JCPOA, will argue strongly against such a decision, contending that it is reckless, ill-advised and will have negative economic and security consequences.

Accordingly, we must explain the grave threat to the US and our allies, particularly Israel. The JCPOA’s vague and ambiguous wording; its manifest imbalance in Iran’s direction; Iran’s significant violations; and its continued, indeed, increasingly, unacceptable conduct at the strategic level internationally demonstrate convincingly that the JCPOA is not in the national security interests of the United States. We can bolster the case for abrogation by providing new, declassified information on Iran’s unacceptable behavior around the world.

But as with prior Presidential decisions, such as withdrawing from the 1972 ABM Treaty, a new “reality” will be created. We will need to assure the international community that the U.S. decision will in fact enhance international peace and security, unlike the JCPOA, the provisions of which shield Iran’s ongoing efforts to develop deliverable nuclear weapons. The Administration should announce that it is abrogating the JCPOA due to significant Iranian violations, Iran’s unacceptable international conduct more broadly, and because the JCPOA threatens American national-security interests.

The Administration’s explanation in a “white paper” should stress the many dangerous concessions made to reach this deal, such as allowing Iran to continue to enrich uranium; allowing Iran to operate a heavy-water reactor; and allowing Iran to operate and develop advanced centrifuges while the JCPOA is in effect. Utterly inadequate verification and enforcement mechanisms and Iran’s refusal to allow inspections of military sites also provide important reasons for the Administration’s decision.

Even the previous Administration knew the JCPOA was so disadvantageous to the United States that it feared to submit the agreement for Senate ratification. Moreover, key American allies in the Middle East directly affected by this agreement, especially Israel and the Gulf states, did not have their legitimate interests adequately taken into account. The explanation must also demonstrate the linkage between Iran and North Korea.

We must also highlight Iran’s unacceptable behavior such as its role as the world’s central banker for international terrorism, including its directions and control over Hezbollah and its actions in Iraq, Syria and Lebanon. The reasons Ronald Reagan named Iran as a state sponsor of terrorism in 1984 remain fully applicable today.

II Campaign Plan Components

There are four basic elements to the development and implementation of the campaign plan to decertify and abrogate the Iran nuclear deal:

1. Early, quiet consultations with key players such as the U.K., France, Germany, Israel, and Saudi Arabia, to tell them we are going to abrogate the deal based on outright violations and other unacceptable Iranian behavior, and seek their input.

2. Prepare the documented strategic case for withdrawal through a detailed white paper (including declassified intelligence as appropriate) explaining why the deal is harmful to U.S. national interests, how Iran has violated it, and why Iran’s behavior more broadly has only worsened since the deal was agreed.

3. A greatly expanded diplomatic campaign should immediately follow the announcement, especially in Europe and the Middle East, and we should ensure continued emphasis on the Iran threat as a top diplomatic and strategic priority.

4. Develop and execute Congressional and public diplomacy efforts to build domestic and foreign support.

III Execution Concepts and Tactics

1. Early, quiet consultations with key players

It is critical that a worldwide effort be initiated to inform our allies, partners, and others about Iran’s unacceptable behavior. While this effort could well leak to the press, it is nonetheless critical that we inform and consult with our allies and partners at the earliest possible moment, and, where appropriate, build into our effort their concerns and suggestions.

This quiet effort will articulate the nature and details of the violations, the type of relationship the US foresees in the future, thereby laying the foundation for imposing new sanctions barring the transfer of nuclear and missile technology or dual use technology to Iran. With Israel and selected others, we will discuss military options. With others in the Gulf region, we can also discuss means to address their concerns from Iran’s menacing behavior

The advance consultations could begin with private calls by the President, followed by more extensive discussions in capitals by senior Administration envoys. Promptly elaborating a comprehensive tactical diplomatic plan should be a high priority.

2. Prepare the documented strategic case

The White House, coordinating all other relevant Federal agencies, must forcefully articulate the strong case regarding U.S. national security interests. The effort should produce a “white paper” that will be the starting point for the diplomatic and domestic discussion of the Administration decision to abrogate the JCPOA, and why Iran must be denied access to nuclear technology indefinitely. The white paper should be an unclassified, written statement of the Administration’s case, prepared faultlessly, with scrupulous attention to accuracy and candor. It should not be limited to the inadequacies of the JCPOA as written, or Iran’s violations, but cover the entire range of Iran’s continuing unacceptable international behavior.

Although the white paper will not be issued until the announcement of the decision to abrogate the JCPOA, initiating work on drafting the document is the highest priority, and its completion will dictate the timing of the abrogation announcement.

A thorough review and declassification strategy, including both U.S. and foreign intelligence in our possession should be initiated to ensure that the public has as much information as possible about Iranian behavior that is currently classified, consistent with protecting intelligence sources and methods. We should be prepared to “name names” and expose the underbelly of the Iranian Revolutionary Guard business activities and how they are central to the efforts that undermine American and allied national interests. In particular, we should consider declassifying information related to activities such as the Iran-North Korea partnership, and how they undermine fundamental interests of our allies and partners.

3. Greatly expanded diplomatic campaign post-announcement

The Administration, through the NSC process, should develop a tactical plan that uses all available diplomatic tools to build support for our decision, including what actions we recommend other countries to take. But America must provide the leadership. It will take substantial time and effort and will require a “full court press” by U.S. embassies worldwide and officials in Washington to drive the process forward. We should ensure that U.S. officials fully understand the decision, and its finality, to help ensure the most positive impact with their interlocutors.

Our embassies worldwide should demarche their host governments with talking points (tailored as may be necessary) and data to explain and justify abrogating JCPOA. We will need parallel efforts at the United Nations and other appropriate multilateral organizations. Our embassies should not limit themselves to delivering the demarche, however, but should undertake extensive public diplomacy as well.

After explaining and justifying the decision to abrogate the deal, the next objective should be to recreate a new counter-proliferation coalition to replace the one squandered by the previous Administration, including our European allies, Israel, and the Gulf states. In that regard, we should solicit suggestions for imposing new sanctions on Iran and other measures in response to its nuclear and ballistic-missile programs, sponsorship of terrorism and generally belligerent behavior, including its meddling in Iraq and Syria.

Russia and China obviously warrant careful attention in the post-announcement campaign. They could be informed just prior to the public announcement as a courtesy, but should not be part of the pre-announcement diplomatic effort described above. We should welcome their full engagement to eliminate these threats, but we will move ahead with or without them.

Iran is not likely to seek further negotiations once the JCPOA is abrogated, but the Administration may wish to consider rhetorically leaving that possibility open in order to demonstrate Iran’s actual underlying intention to develop deliverable nuclear weapons, an intention that has never flagged.

In preparation for the diplomatic campaign, the NSC interagency process should review U.S. foreign assistance programs as they might assist our efforts. The DNI should prepare a comprehensive, worldwide list of companies and activities that aid Iran’s terrorist activities.

4. Develop and execute Congressional and public diplomacy efforts

The Administration should have a Capitol Hill plan to inform Members of Congress already concerned about Iran, and develop momentum for imposing broad sanctions against Iran, far more comprehensive than the pinprick sanctions favored under prior Administrations. Strong congressional support will be critical. We should be prepared to link Iranian behavior around the world, including its relationship with North Korea, and its terrorist activities. And we should demonstrate the linkage between Iranian behavior and missile proliferation as part of the overall effort that justifies a national security determination that US interests would not be furthered with the JCPOA.

Unilateral US sanctions should be imposed outside the framework of Security Council Resolution 2231 so that Iran’s defenders cannot water them down; multilateral sanctions from others who support us can follow quickly.

The Administration should also encourage discussions in Congress and in public debate for further steps that might be taken to go beyond the abrogation decision. These further steps, advanced for discussion purposes and to stimulate debate should collectively demonstrate our resolve to limit Iran’s malicious activities and global adventurism. Some would relate directly to Iran; others would protect our allies and partners more broadly from the nuclear proliferation and terrorist threats, such as providing F-35s to Israel or THAAD resources to Japan. Other actions could include:

- End all landing, docking rights for all Iranian aircraft and ships at key allied ports;

- End all visas for Iranians, including so called “scholarly,” student, sports or other exchanges;

- Demand payment w/set deadline on outstanding US federal court judgments against Iran for terrorism, including 9/11;

- Announce U.S. support for the democratic Iranian opposition

- Expedite delivery of bunker-buster bombs;

- Announce U.S. support for Kurdish national aspirations, including Kurds in Iran, Iraq and Syria

- Provide assistance to Balochis, Khuzestan Arabs, Kurds, others – also to internal resistance among labor unions, students, women’s groups

- Actively organize opposition to Iranian political objectives in the UN

IV Conclusion

This effort should be the Administration’s highest diplomatic priority, commanding all necessary time, attention and resources. We can no longer wait to eliminate the threat posed by Iran. The Administration’s justification of its decision will demonstrate to the world that we understand the threat to our civilization; we must act and encourage others to meet their responsibilities as well.