The president was not eager for war, but he and his advisers had to ponder the risks of leaving Saddam in power in a post-9/11 era.

This article was first published in The Wall Street Journal on February 21, 2023. Click Here to read the original article.

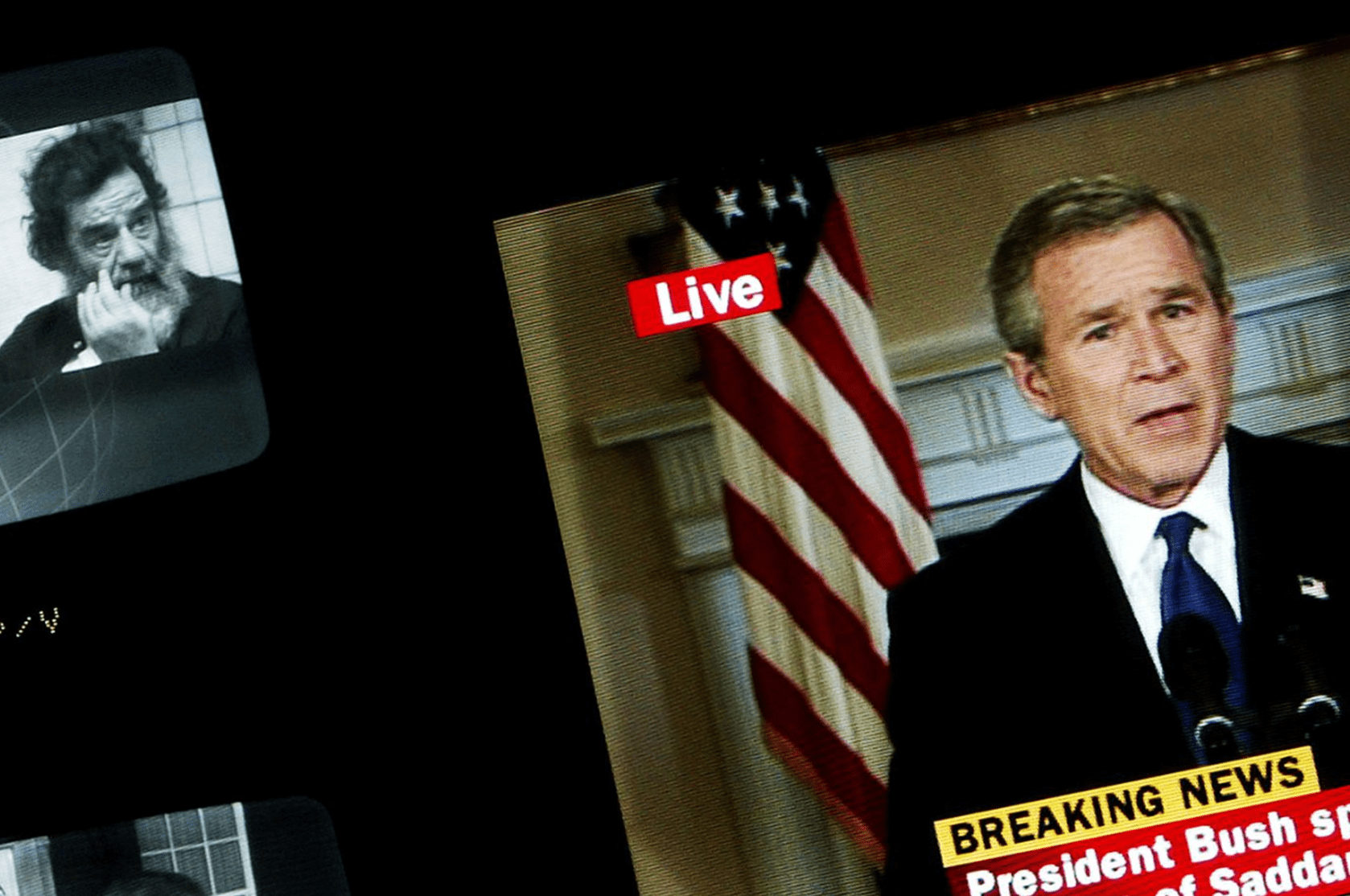

‘I happen to be one that thinks that one way or another Saddam has got to go, and it is likely to be required to have U.S. force to have him go, and the question is how to do it, in my view, not if to do it.” Thus spake then-Sen. Joe Biden on Feb. 5, 2002. He was not alone. The 1998 Iraq Liberation Act, calling for America “to support efforts to remove the regime headed by Saddam Hussein,” passed the Senate by unanimous consent and the House by 360-38. In October 2002, the Senate authorized force to overthrow Saddam by 77-23, and the House by 296-133. In March 2003, when the war began, 72% of Americans supported President George W. Bush’s decision; his approval-disapproval rating was 71%-25%.

Today, supporters of “Bush’s war” aren’t exactly thick on the ground. Opinions on his administration’s policies have so hardened that dispassionate discussion is nearly impossible. Melvyn Leffler’s “Confronting Saddam Hussein,” however, assesses the decision to attack, and its immediate aftermath, in a calm, reasoned and persuasive fashion.

One book cannot resolve the debate over a decadelong event involving so many decisions and phases: Mr. Bush’s 2003 invasion; Saddam Hussein’s overthrow; the long, painful transition to Iraqi rule; Mr. Bush’s 2007 troop surge; Barack Obama’s 2011 withdrawal; and Mr. Obama’s 2014 return. But Mr. Leffler’s account does refute several dishonest criticisms of Mr. Bush’s decisions, while also exposing mistakes that remain inexplicable 20 years later. This is no small feat.

Mr. Leffler, who teaches history at the University of Virginia, demonstrates that Mr. Bush was not eager for war. His advisers did not lead him by the nose. They were not obsessed with linking Saddam Hussein to 9/11. They did not lie about Saddam having or seeking weapons of mass destruction, or WMDs. Their objectives did not include spreading democracy at the tip of a bayonet. To do real research, and then present the results evenhandedly amid the prevailing rancor of U.S. academic and political discourse, is an achievement for which Mr. Leffler will doubtless be rewarded with abuse.

I do disagree, however, with significant aspects of Mr. Leffler’s analysis. He concludes that Mr. Bush’s failures stemmed from “too much fear, too much power, too much hubris—and insufficient prudence.” Given the enormous public support for the war, Mr. Leffler says these errors “were the nation’s failures, the failures of the American people—not all, but many,” an assertion that will profoundly irritate Mr. Bush’s harshest critics, who assign him full culpability.

Thucydides wrote that Nicias, hoping to reverse the Athenians’ decision to attack Syracuse, warned at length about the burdens and risks of such a campaign. Instead, the Athenians, “far from having their enthusiasm for the voyage destroyed by the burdensomeness of the preparations, became more eager for it than ever.” If both Athenian and American democracies lack prudence, does Mr. Leffler agree with Bertolt Brecht’s sardonic suggestion that East Germany’s government, having lost its citizens’ confidence, should have “Dissolved the people and / Elected another”? If nearly everyone gets it wrong in a democracy, Mr. Leffler’s admonitions to decision-makers are essentially useless.

While Bush 43’s father would undoubtedly endorse calls for more “prudence,” is that really more than merely a talisman for national-security decision-makers? Academics should recall Dwight Eisenhower’s handwritten draft statement, hastily written for use if the D-Day invasion had failed. Eisenhower stood ready to take full responsibility for defeat. “My decision to attack at this time and place,” he wrote, “was based upon the best information available.” The same was true for Mr. Bush and his administration. What else could they, or anyone else, base their decisions on?

Data, correct or incorrect, do not dictate supreme command decisions. They emerge from weighing imponderables and uncertainties, upon which reasonable people can disagree. British and American officials weren’t the only people who believed prewar that Saddam had or intended to reacquire nuclear, chemical, and biological weapons. David Kay and Charles Duelfer, leaders of the Iraq Survey Group, concurred after their postwar investigations that removing the dictator was a good thing, and that he intended, after sanctions were lifted, to resume pursuing WMDs, notwithstanding momentary, diversionary, tactical ploys. Tellingly, Mr. Duelfer wrote that “virtually” no senior Iraqi leader “believed that Saddam had forsaken WMDs forever.”

Mr. Leffler describes at length the administration’s deep apprehensions about Iraq or the terrorists it armed using WMDs against the U.S. and its allies, and about the accuracy of their own information and assumptions about that threat. He does not, however, adequately assess the varying propensities of political leaders to accept risk. Some critics, then believing the potential for such attacks to be low, displayed a higher tolerance for that risk. In the wake of the 9/11 attacks, and the anthrax scare weeks later (and unresolved to this day), Bush officials’ tolerance for such risk was close to zero.

Which of the two camps was the more prudent? What would be history’s judgment had America hesitated, and suffered another devastating terrorist attack? That no such attack occurred says more about the merits of overthrowing Saddam than anything else.

Mr. Leffler ends his analysis in the immediate postwar period, which he is entitled to do. He is mercilessly critical of failures in the weeks and months after Saddam’s overthrow, which demonstrated not inadequate planning (Mr. Leffler’s view) but the existence of too many plans that were never effectively reconciled. Nonetheless, Mr. Leffler echoes many of Mr. Bush’s critics by implicitly assuming that actions during that time flowed inexorably from the foundational decision to invade. He is wrong about that.

Even so, “Confronting Saddam Hussein” is an important work. It should inspire more scholarship and less rhetoric on America’s Second Persian Gulf War.