This article appeared in The Washington Examiner on April 26, 2021. Click here to view the original article.

By John Bolton

April 26, 2021

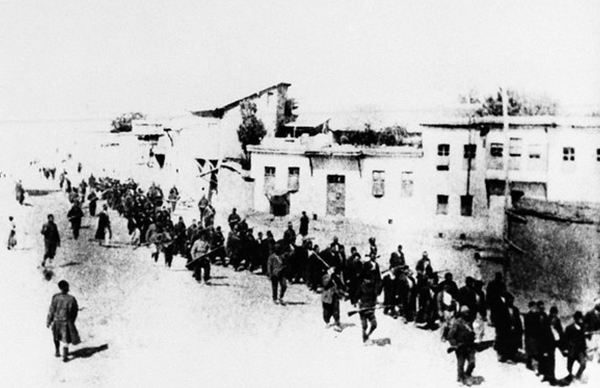

Despite the headlines, President Joe Biden is not the first United States president to declare that the Ottoman Empire’s mass killings of Armenians, beginning on April 24, 1915, constitute genocide. President Ronald Reagan did so in his April 22, 1981, proclamation of “days of remembrance” for the Nazi Holocaust.

He emphasized that “like the genocide of the Armenians before it and the genocide of the Cambodians which followed it, and like too many other such persecutions of too many other peoples, the lessons of the Holocaust must never be forgotten.” Whether Biden’s announcement marks a significant departure from the reticence of other presidents remains to be seen. Although the gruesome historical reality is undisputed, even Reagan’s administration was reluctant to highlight his statement, fearing disruption of relations with Turkey, a key NATO ally.

The pundits immediately characterized Biden’s remarks as merely symbolic, which may prove to be correct. Biden supporters contend that he was underlining the importance of human rights in his foreign policy, but that misses the critical point: ignoring the imperative need, and opportunity, we now have for strategic realignment in the Caucasus. Rewriting history, even to correct it, is too transient an exercise of governmental authority unless more substance follows. International political logic explains Washington’s past hesitations. Turkey’s Cold War role in NATO was critical for immutable geographic reasons, such as anchoring NATO’s line in Europe against the Warsaw Pact and controlling the Dardanelles and the Bosporus. Thereafter, of course, the Soviet Union broke apart, almost all for the better, radical Islamist terrorism arose, and President Recep Tayyip Erdogan took power in Turkey, almost all for the worse.

In the Caucasus, three small states, Georgia, Armenia, and Azerbaijan, are sandwiched between three large, incompatible ones, Russia, Turkey, and Iran, whose interests quite often run counter to the U.S. We cannot unpack the region’s political complexity here, but the key point about Armenia since independence from the Soviet Union is its too-tenacious loyalty to Russia. Locked in a desperate territorial, ethnoreligious struggle with Azerbaijan, deeply fearful of conflict with Turkey, and justifiably wary of Iran, Yerevan looked to Moscow for support. Doing so resulted in an Armenian foreign policy that is otherwise totally inexplicable. For example, on April 21, at the Organization for the Prohibition of Chemical Weapons, Armenia, along with the likes of Russia, China, and Iran, voted unsuccessfully against a resolution stripping Syria of its vote in the organization for using chemical weapons against its own people. Three decades of pro-Moscow policy has been wholly misguided.

Armenia’s highest international priority, the conflict with Azerbaijan over Nagorno-Karabakh, is an outgrowth of Moscow’s Soviet-era internal boundary drawing, yet another failed effort to answer what Marxists called “the nationalities question.” When its most threatening recent crisis arose, the 2020 flare-up with Azerbaijan, which was aided by Turkey, Armenia’s dependence on Russia proved almost entirely worthless. Armenia suffered significant military reversals, but contrary to Yerevan’s expectations, Moscow essentially imposed a cease-fire that nearly collapsed Armenia’s government and acknowledged its territorial losses. With friends like that…

Armenia’s attachment to Russia has been tragic, especially given the large number of Armenian Americans who could have focused Washington’s attention on the plight of their ancestral homeland. During a 2018 visit to Yerevan, I asked Armenian analysts why this had not happened. Several pointed to the Armenian American focus on getting U.S. recognition of the genocide rather than on contemporary realities. Whether right or wrong, Biden nonetheless has an opportunity to place a higher U.S. priority on Armenia’s plight. The Armenian American community should now focus on the negative consequences of Yerevan relying on Moscow, and Washington should worry more about bringing peace and stability to all three Caucasus countries. We have no interest in any of them aligning with, or being exploited by, the regimes in Iran, Russia, and Turkey.

Certainly, Erdogan’s Turkey is dangerous for Armenia, but grounds for hope exist. Dissatisfaction with Erdogan is rising, reflected in his party’s defeat in key 2019 local elections, such as Istanbul and Ankara, making Turkey’s looming 2023 presidential race critical for its future direction. It is premature to dismiss Turkey as a NATO ally, at least until we see if Erdogan permits free and fair national elections, which will happen only under Western pressure and scrutiny. Turkey itself should long ago have recognized the Armenian tragedy, but its internal politics have made that impossible. Washington should not underestimate the difficulties of change even now, but Erdogan’s departure opens many possibilities for Turkey to rehabilitate itself.

No one seriously believes that Caucasus politics is anything but complex. Inadequate U.S. attention for three decades after the Soviet Union’s dissolution, however, has not made it any easier. If Biden’s genocide statement is more than domestic U.S. politics, an increase in awareness can only bolster Washington’s position in the region.