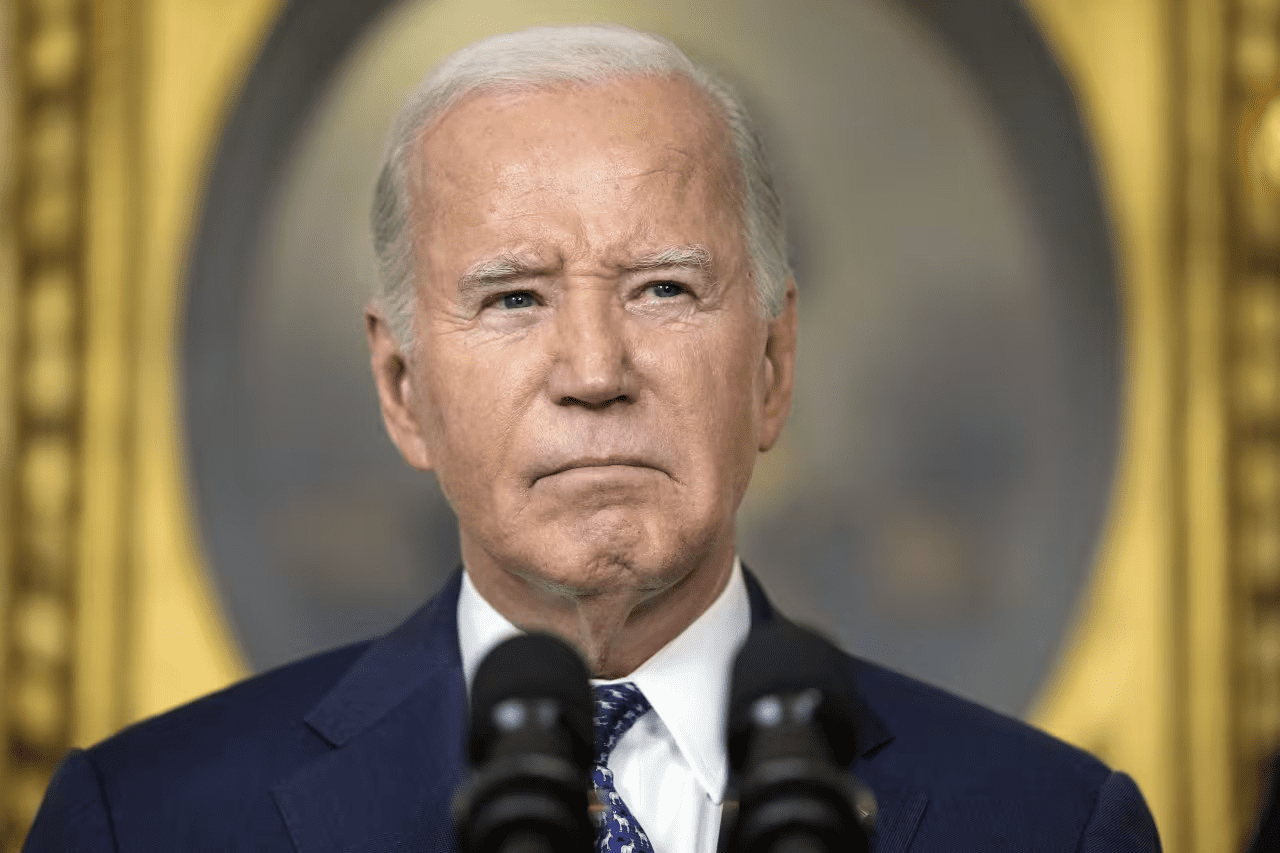

Joe Biden’s decision to withdraw from the presidential race effectively makes him a lame duck. The odds favored his achieving this status on Nov. 5 anyway, but America now faces a nearly 100-day longer interregnum than in prior transition periods. We may focus on the election campaign, but the wider world worries what Washington’s global role will be for the next six months.

History affords no clear answer. The constitutional rule that we have only one president at a time is often hard for Americans, let alone foreigners, to grasp. The dangers posed by uncertainty about who’s in charge even in normal transitions are exacerbated by a weak incumbent no longer seeking re-election. U.S. adversaries, and even some allies, will see opportunities to advance their interests. Nor can we rule out what an otherwise responsible, but disappointed and possibly bitter lame duck might consider doing as his tenure in office dwindles.

The national-security risks and opportunities facing lame-duck presidents vary with the international environment and their own beliefs and proclivities. This year, the length of Mr. Biden’s lame-duckery offers unique complexities. Given the 22nd Amendment’s two-term limit, one could argue that presidents become lame ducks on their second Inauguration Day, but that obscures the key differences between how the Reagan, George W. Bush and Obama administrations ended versus the “defeated” Lyndon Johnson, Carter and Biden presidencies.

Past lame-duck periods don’t uniformly demonstrate presidential (or national) weakness. While Mr. Biden may simply slumber through the remainder of his term, that outcome is far from preordained. For good or ill, presidents retain broad discretion, and their approaches have ranged from high-minded to vindictive, with enormous consequences for their successors.

Wide-ranging actions by lame ducks are sometimes simply unnecessary. Transitions between same-party presidents, which may or may not happen this cycle, are rare, but in 1988-89 Ronald Reagan worked hard to facilitate Vice President George H.W. Bush’s accession to office.

In some cases, lame-duck presidents simply do their own thing, irrelevant to their successor. Bill Clinton continued to chase the gray ghost of Middle East peace while Gov. Bush and Vice President Al Gore slugged it out in the Florida recount. During the 2008-09 financial crisis, global disarray so thoroughly dominated international affairs that the U.S. didn’t seem particularly vulnerable.

Lame-duck periods during party-to-party transitions are the most dangerous, almost unavoidably so, whether the outgoing president was defeated or simply trying to finish without impairing his party’s nominee. Freighted with potential consequences, conflicts between the lame duck and his successor, and between their teams, are often testy, reflecting just-concluded campaigns, and most acutely raising the question of who’s in charge.

The 1980-81 Carter-Reagan transition was such a case, dominated by the Iran hostage crisis. The campaign had been bitter, with mutual recriminations on many fronts, including about the hostages. Fortunately, a potentially destructive Carter lame-duck period was averted by a deal that suited all the actors: releasing the hostages (a plus for Mr. Carter) after Reagan was actually inaugurated (a plus for Reagan), bringing a temporary end to Tehran-Washington tensions (a plus for Tehran). Nonetheless, with controversies like the wars in Ukraine and the Middle East and high tensions with China, the prospect of conflict clouding Biden’s lame-duckery is palpable.

After the 1992 election, George H.W. Bush intervened militarily in Somalia to open closed channels for humanitarian assistance. The White House made it clear Bush would act as he saw best while still president, but he offered to withdraw all U.S. forces before Mr. Clinton’s inauguration if the new president desired. Mr. Clinton chose to continue the mission, later mistakenly expanding it, but the two presidencies functioned smoothly during the handover.

In stark contrast, Barack Obama chose to settle scores with Israeli Prime Minister Benjamin Netanyahu in the United Nations Security Council. By abstaining on Resolution 2334 (passed 14-0-1 on Dec. 23, 2016), Mr. Obama figuratively knifed both Mr. Netanyahu and the incoming Trump administration, which had openly advocated a U.S. veto. While abstaining wasn’t a startlingly new position, it was unnecessary and vindictive, auguring in a small way what a determined lame-duck could do.

Mr. Trump made the 2020-21 transition perilous by trying frantically and erratically to thwart the results of the 2020 election. Whether one considers the Jan. 6 riot and the runup to it an insurrection or simply disgraceful and disqualifying for Mr. Trump, his lame-duck period was the second-worst in American history (after James Buchanan to Abraham Lincoln in 1860-61).

While it’s difficult to predict what Mr. Biden may do as a lame duck, or what external threats or crises might develop, our current circumstances hold uncharted dangers. Congress, the candidates and especially the American public need to begin thinking about the challenges ahead, and monitoring Mr. Biden’s prolonged lame-duck status closely.

Mr. Bolton served as White House national security adviser, 2018-19, and ambassador to the United Nations, 2005-06. He is author of “The Room Where It Happened: A White House Memoir.”

This article was first published in Wall Street Journal on July 21, 2024. Click here to read the original article.