Remembering his virtues and public service

This article was first published in The National Review on August 24, 2023. Click Here to read the original article.

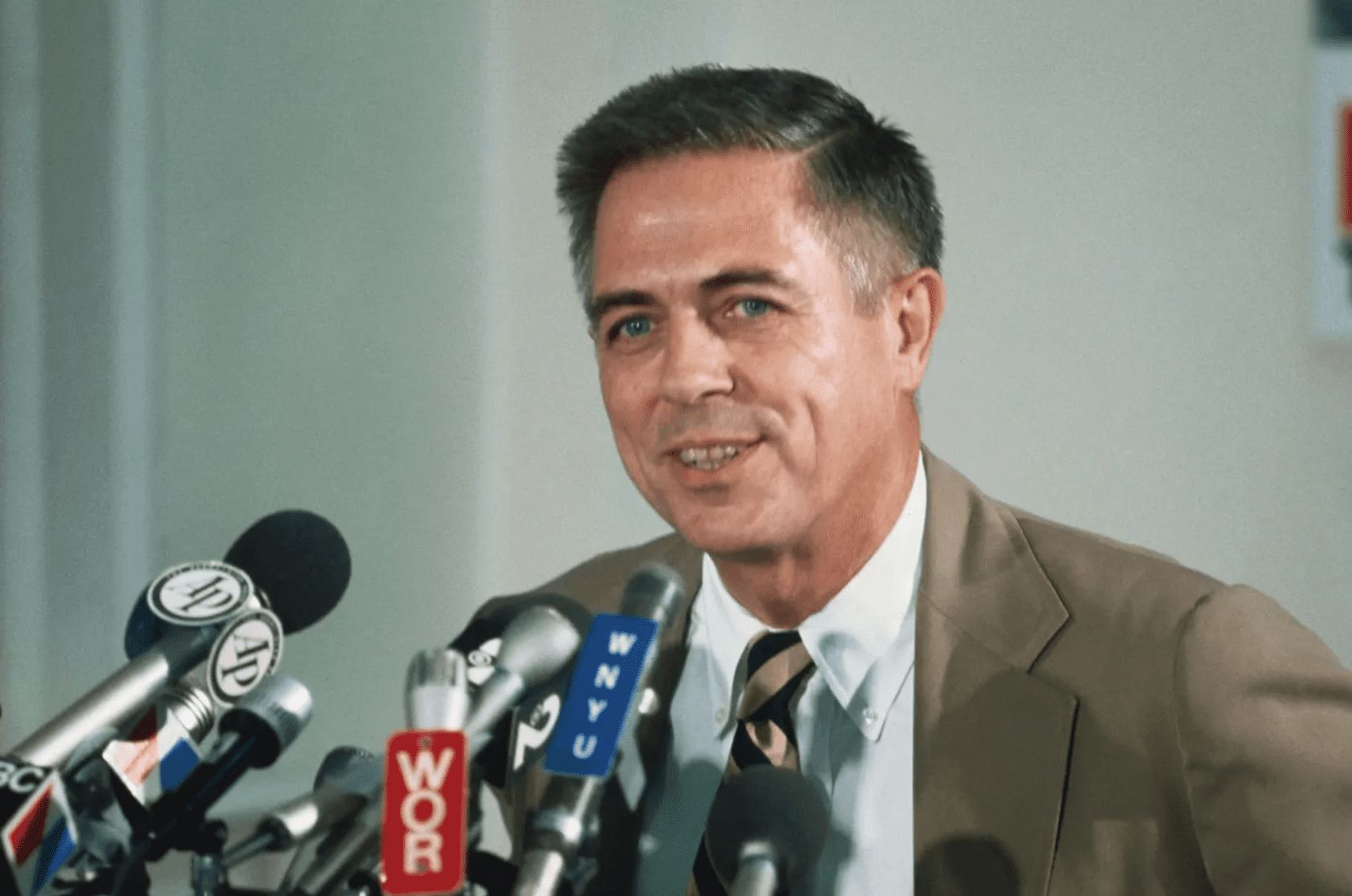

Jim Buckley was the very model of what our founders had in mind for America’s civic leaders, rare at any point in our history, and perhaps rarest of all in today’s politics. His résumé alone does not tell the full story, although he was one of the few people in our history to serve in senior positions in all three branches of the federal government.

More important than the offices he held were the virtues he demonstrated consistently throughout his public service. Jim had character, an attribute that allowed him to withstand the turmoil of politics or business without suffering adverse effects on his behavior or his treatment of others. He was a gentleman in all the appropriate ways: respectful, courteous, and thoughtful, not because he was weak, but precisely because he was secure. He had strong religious faith and political principles, both of which transcended immediate personal gain, whether in fame or fortune. He was educated, unlike so many today who possess college degrees but little more.

Perhaps the most important of Jim Buckley’s virtues, an example to his fellow citizens in our time, was his courage. Quiet courage, as he was not a man to shout, boast, pontificate, or slander, an inner strength that impelled him against daunting odds to do what he saw as right.

In 1970, for example, he ran for the United States Senate from New York on the Conservative Party line, challenging the incumbent Republican, Charles Goodell, for not being, well, Republican. After his third-place finish as a Conservative in 1968, following his brother Bill’s unsuccessful 1965 run for mayor of New York, one could hardly avoid worrying that this candidacy could be a waste of time. Goodell, however, appointed by Governor Nelson Rockefeller to fill the vacancy caused by Robert Kennedy’s assassination, was sufficiently lackluster that Buckley won in a three-way race. I was in Army training at Fort Polk, La., at the time and ignored the rules against playing radios after taps, to listen for election results in distant lands. It was my happiest moment at Fort Polk.

In the Senate, Jim was not a party of one but caucused with Republicans. In his 1976 reelection campaign, he ran on both the Republican and Conservative lines. Unfortunately, he lost to Daniel Patrick Moynihan, causing enormous turmoil at National Review. In 1975, emulating Time magazine, brother Bill had created a “man of the year” award, naming Moynihan as the first honoree. After such flattery, Moynihan had the effrontery to beat “the sainted junior senator,” causing Bill to terminate the man-of-the-year program forever. Sic transit gloria mundi._

During Jim’s Senate tenure, he did two things that stand out as remarkable acts of courage, not just in his personal story, but in America’s history.

The first was his role in the Watergate crisis. As Richard Nixon’s presidency disintegrated, and the House of Representatives moved toward impeachment, levels of partisanship and acrimony rose higher and higher. Through the investigations of the Senate Watergate Committee, the evidence of the break-in and subsequent, ultimately politically fatal, cover-up dominated political discourse in Washington and the country generally. The stakes were high, and emotions were higher. Republicans, in Congress and out, could see that Nixon was badly wounded, but he seemed determined to fight to the very end.

Until, that is, Jim Buckley rose on March 19, 1974, to speak on the Senate floor. He called on Nixon to resign, the first conservative Republican senator to do so, saying: “There is one way and one way only by which the crisis can be resolved, and the country pulled out of the Watergate swamp. I propose an extraordinary act of statesmanship and courage — an act at once noble and heartbreaking; at once serving the greater interests of the nation, the institution of the presidency, and the stated goals for which he [Nixon] so successfully campaigned.”

This call for Nixon to act on his better instincts was not at all unusual for Buckley but seemed somewhat misplaced, given his audience. Nonetheless, as the House impeachment process unfolded, partisan barriers broke down before the accumulating evidence. Nixon ultimately resigned in August 1974 after being told by Republican leaders, including “Mr. Conservative,” Barry Goldwater, that the Senate would convict him if presented with articles of impeachment. Watergate taught many lessons, but one of the clearest was the standard that Jim Buckley set for civic virtue in American leaders: dealing forthrightly with reality, based on high principle.

In the immediate aftermath of Nixon’s fall, innumerable “reforms” were proposed in Congress, almost all constitutionally flawed and dangerous. Perhaps the worst were amendments to federal campaign-finance laws, universally hailed by the press, Democrats, and liberals, essentially all of which were ruinous to the good health of American politics. These included nearly prohibitive limitations on campaign contributions, candidate expenditures, and independent expenditures; disclosure of even small contributions and expenditures; public financing of presidential campaigns and conventions; and a Federal Election Commission to enforce these laws, only one-third of whose members would be appointed by the president, the others by the Senate president pro tem and House speaker.

Woe to those who dared oppose the great thunderers of the media, always vigilant in protecting their own press freedoms but casual at best when it came to protecting the First Amendment’s other free-speech protection — political activity by individual citizens and their voluntary associations.

None of that bothered Jim Buckley in the slightest, bringing him to his finest hour and bringing me, happily, the chance to work with and get to know him. During Watergate, I was a law student and worked as a research assistant to Professor Ralph Winter. Winter (later a Reagan-appointed Second Circuit judge and a powerful voice for sound constitutional interpretation) wrote extensively on why campaign-finance activity should receive the First Amendment’s full protection. Dave Keene, then a Buckley staffer, who had hired me as a summer intern in Vice President Spiro Agnew’s office in 1972 (Watergate summer, for those who weren’t around), called to ask about possibly challenging in court the new campaign-finance law’s constitutionality. Winter was ready immediately.

By the time Congress was putting the last touches on the legislation, I was practicing law in Washington, readying the filings that would initiate the case now known as Buckley v. Valeo. On January 30, 1976, the Supreme Court declared limits on candidate, campaign, and independent expenditures unconstitutional, and also held the Federal Election Commission’s appointment process unconstitutional, thus striking down a federal agency for the first time since the New Deal.

Collectively, Jim Buckley and his eleven coplaintiffs, including former senator Gene McCarthy, looked like they had stepped out of the bar scene in Star Wars, but that was emblematic of Buckley’s appreciation for finding allies in unlikely places. And I must say, listening to conversations between Buckley and McCarthy was the kind of treat few will hear in today’s Senate.

Henceforward, anyone who reads American constitutional law will learn of Buckley v. Valeo, a case that came into being because of the unique courage and principles of one man. There is much more to say about Jim Buckley, but I cannot emphasize enough what luster he brought to our country, and how much of an honor it was to know him.