This article appeared in The Washington Examiner on March 1, 2021. Click here to view the original article.

By John Bolton

March 1, 2021

America’s 20-year history in Afghanistan inevitably colors debate about the U.S. interests at stake and what to do there next. Unfortunately, the debate often deteriorates into a war of bumper-sticker slogans: “ending endless wars” versus “standing by our commitments.”

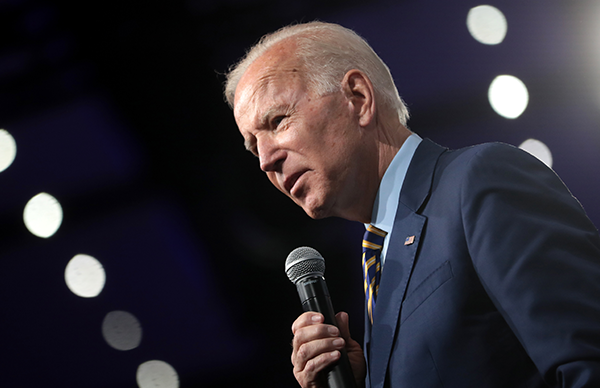

Newly-inaugurated, President Biden now has a unique opportunity. Inheriting last year’s deeply flawed withdrawal agreement with the Taliban, Biden faces a May 1 decision whether to completely remove U.S. forces. In theory, earlier U.S. force reductions and the final departure were to be “conditions based.” Coming only in return for the Taliban’s ending of its support for international terrorists, its making peace with Afghanistan’s government, and its action to reduce in-country violence. No one seriously argues these conditions can be met by May 1. Accordingly, Biden has a critical choice.

The congressionally-mandated, bipartisan Afghanistan Study Group recently advocated extending the withdrawal deadline, essentially to buttress the withdrawal agreement’s conditionality. Biden thus has ample political cover to maintain the U.S. presence in Afghanistan, although he would be wrong to believe that the underlying deal requires only modest re-torquing to make it viable. One can certainly doubt that the Taliban will ever honor their commitments. In what is hopefully a renewed era of “normalcy” in policy debates, however, an extension also affords time to recalibrate our basic interests and stop the bumper-sticker bombardment.

Biden should conclude that the Taliban has already so materially breached the peace deal that it no longer binds Washington.

America’s basic interest is not facilitating an abstract Afghan “peace process,” like the Middle East “peace processing” mirage. The United States wants to ensure that Afghanistan is not a base for terrorist operations. “Peace,” as defined in the Afghan context, relates to this objective but does not guarantee it. Global terrorist operations can be organized and launched from states that appear and may well be entirely peaceful. While a stable, peaceful Afghanistan could enhance the possibility of preventing terrorist activities emanating from its territory, it is, bluntly stated, not essential.

Moreover, Washington is not responsible for building stability and peace there or anywhere else, especially when to do so means major changes in the fabric of Afghan society. Afghans can do their own nation-building in their own good time if they so desire. For America, the touchstone is our strategic interests, not complete congruence with Afghanistan’s. If it is fundamentally important for U.S. security to conduct “forward defense” there, and it is, that calculus does not change depending on whether the Afghan government’s military or political performance meets our expectations. We can certainly assist and urge them to do better, but their deficiencies, militarily or in reconciling with the Taliban, only bolster the argument that protecting America requires our continued presence. As Kabul is responsible for its domestic policies, we are responsible for our security.

If, therefore, it is not in our interest to withdraw, we should not, even if the conflict between the Taliban and non-terrorist Afghans continues indefinitely. This is not simply a squabble over nomenclature but over strategic goals. As with all valid long-term objectives, we must be prepared to persist for the long-term in order to achieve them. This is not what the Afghanistan Study Group recommends or what Biden probably prefers, but it is the only approach with a prospect for enduring success. As long as the Taliban are correct when they say, “you have the watches, we have the time,” we are doomed to fail.

There is another key American objective in Afghanistan, afforded by geography, not adequately recognized in previous administrations.

Situated between one nuclear-weapons state, Pakistan, and an aspiring nuclear-weapons state, Iran, Afghanistan provides a forward operating base for close scrutiny and access across its eastern, western, and southern borders. Not all intelligence, even today, is gathered from space by national technical means. Being proximate to two potential nuclear threats is not an asset to discard lightly. For the Biden administration in particular, mistakenly eager to rejoin the 2015 Iran nuclear deal, a continuing U.S. military presence in Afghanistan constitutes an insurance policy not merely against a resurgence of terrorism but against the growing nuclear-proliferation menace in the neighborhood.

U.S. interests in Afghanistan are also priorities for NATO allies, although the counter-proliferation responsibility falls more heavily on Washington. But there is no conflict between these interests that should inhibit continued NATO involvement in counter-terrorism programs, which thereby also support, albeit indirectly, the counter-proliferation programs. At present, NATO allies have roughly twice as many troops in Afghanistan as the U.S., a ratio that would imply a larger NATO presence if America’s deployment rose. Such an increase, possibly with similar enhancements in Iraq, could also have political benefits inside NATO, repairing some of the damage inflicted on alliance cooperation in recent years.

Britain’s Lord Palmerston urged that a statesman’s duty is to follow his country’s interests. The impending May 1 deadline in Afghanistan will test whether President Biden understands that logic.